Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- 1. “Bats Are Blind”

- 2. “Goldfish Only Have a Three-Second Memory”

- 3. “Bulls Hate the Color Red”

- 4. “Lemmings Commit Mass Suicide”

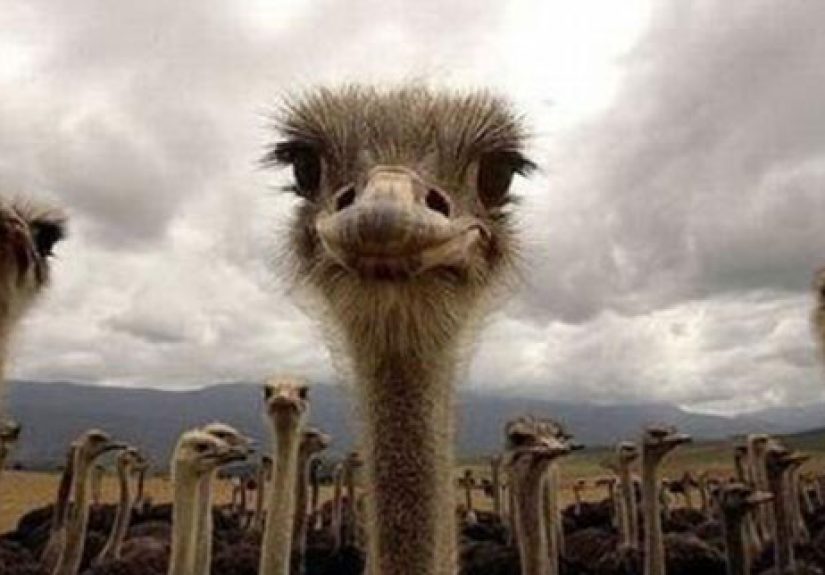

- 5. “Ostriches Bury Their Heads in the Sand”

- 6. “Mother Birds Will Abandon Babies Touched by Humans”

- 7. “Sharks Don’t Get Cancer”

- 8. “Porcupines Can Shoot Their Quills”

- 9. “Dogs Sweat Only Through Their Tongues”

- 10. “Touching a Toad Will Give You Warts”

- Why These Wrong Animal “Facts” Stick Around

- Real-Life Experiences With Wrong Animal Facts

- The moment you realize the bat can see you

- The goldfish who remembers dinner time

- Ostriches, up close and very much not hiding

- The porcupine that proves a point (painfully)

- From shark miracle cure to conservation wake-up call

- Kids, toads, and the wart conversation

- Unlearning is part of being curious

Animals are already weird and wonderful enough, but humans apparently looked at bats, bulls, and goldfish and said,

“Cool… now let’s make up completely fake facts about them.” Over time, these stories turned into “common knowledge”

that gets repeated in classrooms, cartoons, and family dinners like they’re carved in scientific stone.

The good news? Science has receipts. Many of the most famous “animal facts” are wildly inaccurate, wildly outdated,

or just plain wild. In this article, we’ll debunk ten of the most persistent myths, explain where they came from,

and show what’s actually going on in the animal kingdom. Spoiler: the truth is usually way more interesting than

the myth.

So buckle up for some gentle ego bruising. If you’ve ever said “blind as a bat” or worried about getting warts from

a toad, this one’s for you.

1. “Bats Are Blind”

Where the myth came from

The phrase “blind as a bat” is so common that it feels like a scientific fact. Bats fly at night, use echolocation,

and aren’t exactly easy to observe up close. For centuries, people assumed that if an animal uses sound to navigate,

it must not be able to see at all.

What’s really true

Bats are absolutely not blind. In fact, many species have perfectly good vision, and some see better than humans in

low light. They simply layer their superpowers: eyesight plus echolocation. Vision helps them orient to light and

landmarks, while echolocation gives them a detailed map of their surroundings in the dark, right down to the

flutter of an insect’s wings.

So the next time someone says “blind as a bat,” feel free to correct them: bats can see, navigate, hunt, and avoid

obstacles in conditions where we’d walk directly into a doorframe.

2. “Goldfish Only Have a Three-Second Memory”

The myth that launched a thousand jokes

Goldfish have become the unofficial mascot of forgetfulness. The idea that they can only remember things for

three seconds is repeated constantly in pop culture, usually as a punchline for being clueless or distracted.

What science actually shows

Researchers and educators who study fish behavior have repeatedly shown that goldfish can remember information for

weeks or even months. In experiments, goldfish learned to navigate mazes, recognize specific patterns, and respond

to feeding cues at certain times of day. They were able to recall what they learned long after three seconds had

passedmore like several weeks later.

In practical terms, that means your goldfish probably remembers the layout of its tank, your feeding schedule,

and maybe even the fact that you tap the glass when you walk by (which, by the way, they would prefer you didn’t).

3. “Bulls Hate the Color Red”

Blame the cape, not the color

Thanks to bullfighting scenes in movies and cartoons, most people believe bulls go into a rage at the sight of

anything red. The matador’s bright red cape seems like an obvious trigger. No wonder the myth stuck.

How bulls really see the world

Cattle, including bulls, don’t perceive red the way humans do. Their eyes are essentially color-blind to red

tones. What actually sets a bull off in the ring is movement, not color. The cape could be blue, yellow, or plaid

with flamingos on itif it’s whipping around dramatically, the bull will charge.

The cape is traditionally red partly for showmanship and partly to help disguise blood during a fight. It’s a human

choice, not a bull’s personal fashion enemy.

4. “Lemmings Commit Mass Suicide”

A myth literally pushed off a cliff

The image of lemmings hurling themselves off cliffs in huge groups is one of the most persistent animal legends.

It’s been used as a metaphor for mindless human behavior for decades.

What really happened

In reality, lemmings do not gather to intentionally dive to their deaths. The myth exploded after a 1950s Disney

nature film staged a dramatic “mass suicide” sequence by physically herding lemmings off a cliff for the camera.

That footage went on to win awardsand mislead an entire generation.

Lemmings do migrate, and when populations boom, they may travel long distances and sometimes fall or drown by

accident. But that’s very different from an organized, deliberate death march.

5. “Ostriches Bury Their Heads in the Sand”

Why this one refuses to die

“Burying your head in the sand” has become shorthand for avoiding reality, supposedly based on ostriches hiding

from danger by literally shoving their heads into the ground. It’s such a neat metaphor that people rarely stop to

ask whether it makes sense for a six-foot bird to suffocate on purpose.

What ostriches are actually doing

Ostriches do not bury their heads to hide. When threatened, they usually runfast. They can sprint at highway

speeds, and if they can’t outrun a predator, they’ll fight with kicks powerful enough to injure or kill. When an

ostrich appears to have its head down near the ground, it’s typically:

- Turning its eggs in a shallow nest.

- Pecking at food on the ground.

- Lowering its head to blend in with the horizon when lying low.

From far away, a flattened bird body and a hidden neck can look like a head in the sandbut it’s an optical

illusion, not a stress-management strategy.

6. “Mother Birds Will Abandon Babies Touched by Humans”

The well-meaning warning

Many of us were taught as kids: “Never touch a baby birdits mother will smell you and reject it.” Adults say this

to stop children from grabbing wildlife, which is a good goal. Unfortunately, the explanation is wrong.

How bird senses really work

Most songbirds have a relatively weak sense of smell. They aren’t sniffing their chicks like tiny feathered bloodhounds.

If a chick is returned to the nest after briefly being handled, the parents usually continue caring for it as normal.

What can cause abandonment is repeated disturbance or the nest being destroyed, not a quick rescue. The better rule

of thumb is: observe from a distance, intervene only when necessary (for example, an obviously injured bird), and

follow local wildlife guidelines.

7. “Sharks Don’t Get Cancer”

How a marketing slogan became a “fact”

You may have seen books or supplements boasting that “sharks don’t get cancer,” usually while trying to sell you

shark cartilage as a miracle cure. The idea is that sharks are so evolutionarily successful that they must be

disease-proof.

The real story behind shark health

Scientists have documented tumors in multiple shark species. Sharks do get cancer and other diseases; it’s just

relatively rare and historically under-reported because studying wild marine animals is difficult. Research on shark

biology has taught us a lot about immune systems and tumor growth, but that doesn’t translate into “eat shark parts

and live forever.”

On top of being scientifically shaky, harvesting sharks for unproven health products harms already vulnerable

species. The best way to “honor” sharks is to leave them in the ocean, not turn them into supplements.

8. “Porcupines Can Shoot Their Quills”

The missile-mammal myth

Porcupines have such dramatic defenses that people assumed there must be some kind of long-range weapon involved.

Stories have circulated for centuries about porcupines launching quills like darts at predatorsor unlucky hikers.

How quills really work

Porcupines cannot shoot their quills. The quills are modified hairs that detach on contact. When a predator gets too

close, the porcupine turns its back, bristles, and may swat with its tail. Anyone who gets stuck has gotten way too

closeliterally.

The quills themselves are nasty: barbed, painful, and difficult to remove. But they still require physical contact.

If you’re several feet away, the porcupine is not secretly artillery.

9. “Dogs Sweat Only Through Their Tongues”

Panting is only part of the picture

A lot of people think panting is the “dog version” of sweating and that dogs only cool themselves through their

mouths. That’s half-right at best and misses some important biology.

How dogs actually keep cool

Dogs do have sweat glands, but they’re located mainly in their paw pads, not all over their skin like ours. Those

glands can release moisture when a dog is hot or stressedsometimes you’ll even see damp paw prints on a hot day.

Panting is their main cooling strategy. When dogs pant, moisture evaporates from their tongue, nasal passages, and

the lining of their lungs. Combined with increased blood flow to the face and ears, that helps shed heat efficiently.

So no, they don’t “sweat only through their tongues”their bodies use several tools at once.

10. “Touching a Toad Will Give You Warts”

Blame the bumps, not the amphibian

The classic childhood warning goes something like: “Don’t pick up that toad, or you’ll get warts!” Toads often have

bumpy skin, so people historically assumed those bumps were contagious.

What actually causes warts

Human warts are caused by specific strains of human papillomavirus (HPV). It’s a human virus, spread by contact with

infected skin or surfacesnot frogs, not toads, not newts, not salamanders. Amphibians can’t give you warts, even if

their own skin looks like it has them.

That doesn’t mean you should manhandle every frog you see. Amphibians have delicate skin that can be harmed by

chemicals, sunscreen, or soap on human hands. The risk is to the animal, not to your complexion.

Why These Wrong Animal “Facts” Stick Around

So how did all of these totally wrong animal ideas become so popular? A few patterns show up again and again:

- They make good stories. “Lemmings jump off cliffs” or “ostriches bury their heads” are vivid,

memorable images that are easy to repeat. - They simplify complex behavior. Animal biology is detailed and messy. Myths are short,

dramatic, and easy to remember. - They get recycled in media. Cartoons, movies, and even outdated textbooks can keep myths alive

long after scientists have moved on. - They sound like warnings. “Don’t touch baby birds” and “don’t pick up toads” sound like safety

tips, so adults pass them on with good intentions.

The problem is that these myths don’t just misinform us. They can affect how we treat animalsfearing bats, ignoring

shark conservation, or assuming wildlife doesn’t need protection because it’s “invincible.” Knowing the real facts

helps us make smarter, kinder choices.

Real-Life Experiences With Wrong Animal Facts

These myths aren’t just abstract ideas. Most of us have bumped into them in real lifesometimes in hilarious ways,

sometimes in ways that change how we see animals forever.

The moment you realize the bat can see you

Imagine walking through a zoo’s nocturnal house, squinting at dimly lit enclosures while a guide cheerfully

explains that the bats can see just fineeven if you can’t. For many visitors, that’s a genuine “wait, what?”

moment. People instinctively lean back from the glass, suddenly very aware that the “blind” creatures dangling above

them are not only aware of their presence, but tracking movement with both echolocation and eyes.

That realization tends to flip fear into fascination. Once you understand that bats aren’t helpless, erratic flyers

but highly skilled navigators, you start appreciating them as complex mammals instead of Halloween props.

The goldfish who remembers dinner time

Many goldfish owners notice that their fish swim excitedly to the front of the tank at the same time every day.

They’re not guessing; they’re anticipating. People who grew up joking that goldfish “forget everything” are often

surprised when their supposedly clueless pet clearly remembers where the food appears and who usually brings it.

In classrooms, teachers sometimes use goldfish experiments to show students how learning and memory really work.

When kids see a fish navigate a simple maze to reach food after days or weeks, it’s hard to hang on to the

three-second myth. That tiny demonstration quietly rewires how they think about animal intelligence.

Ostriches, up close and very much not hiding

Safari guides and zookeepers tell a similar story: people arrive expecting to see ostriches with their heads in the

sand. Instead, they’re greeted by tall, alert birds that either stroll around casually or bolt at ridiculous speeds

across the landscape. If an ostrich feels threatened, it might crouch and stretch its neck along the ground to

blend in, but visitors quickly see there’s no comedic self-burial happening.

Guides often use that moment to explain how many other “facts” people brought with them are also off-base. It becomes

a gentle invitation to stay curious instead of defensive: if we were wrong about ostriches, what else might we be

wrong about?

The porcupine that proves a point (painfully)

Veterinarians and wildlife rehabbers regularly see dogs come in with mouths full of porcupine quills. Owners sometimes

insist, “He wasn’t even that closethe porcupine must have shot them!” But when the story gets unpacked, it usually

turns out the dog got a little too curious, rushed in, and met a very spiky reality.

Once people learn that porcupines can’t fire quills from a distance, they start telling a different story: instead

of a “weaponized” animal launching attacks, you have a shy creature using a last-resort defense when someone refuses

to respect its space. That shift matters for how we talk about wildlife and who we think is “at fault” when there’s

a painful encounter.

From shark miracle cure to conservation wake-up call

The shark-cancer myth has had real-world consequences. Some people bought shark cartilage supplements thinking they

were tapping into a natural shield against disease. Later, when they learned that sharks do get cancer, and that

harvesting them for cartilage puts additional pressure on already vulnerable populations, the emotional whiplash was

intenseembarrassment, frustration, even anger at being misled.

For a lot of divers, surfers, and ocean lovers, that myth becoming unraveled was a turning point. Instead of seeing

sharks as invincible villains or magical cures, they started seeing them as wildlife in need of protectionanimals

with long lifespans, slow reproduction, and a crucial role in marine ecosystems.

Kids, toads, and the wart conversation

Ask any parent, teacher, or camp counselor: the “toads cause warts” myth is still alive and kicking. The funny thing

is what happens when kids hear the real explanation. When you tell them that human warts come from a virus we pass to

each othernot from frogsthey usually look at their own hands like, “So we are the problem?”

That little shift can be powerful. Instead of fearing harmless amphibians, kids start focusing on actual hygiene:

washing hands, not sharing personal items, and taking care of cuts and scrapes. Plus, more kids feel comfortable

watching frogs and toads calmly from a respectful distance instead of recoiling in disgust.

Unlearning is part of being curious

The most valuable “experience” tied to wrong animal facts is the feeling you get when you update your understanding.

It’s humbling at firstno one loves realizing they’ve been confidently wrong for yearsbut it’s also energizing. If

we can unlearn ten myths about animals, we can unlearn other lazy assumptions, too.

The next time you hear a dramatic claim about animal behavior, pause before repeating it. Ask where it came from,

whether it still matches current research, and how it might affect how people treat that species. Curiosity is the

best habit we can bring to the animal kingdomand it leads to way better stories than “goldfish forget everything”

ever did.