Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Quick Table of Contents

- 1) Guy Fawkes (Executed 1606)

- 2) William Wallace (Executed 1305)

- 3) Jan Hus (Executed 1415)

- 4) Giordano Bruno (Executed 1600)

- 5) Sir Thomas More (Executed 1535)

- 6) William Tyndale (Executed 1536)

- 7) King Charles I (Executed 1649)

- 8) King Louis XVI (Executed 1793)

- 9) Maximilien Robespierre (Executed 1794)

- 10) John Brown (Executed 1859)

- Bonus: Sacco & Vanzetti and Julius Rosenberg (Why “modern” executions still haunt us)

- Reader Experiences: What These Stories Feel Like Up Close (About )

- Conclusion

Content note: This is a historical article about capital punishment. To keep it informative (and readable), it avoids graphic details while still explaining what happened and why it mattered.

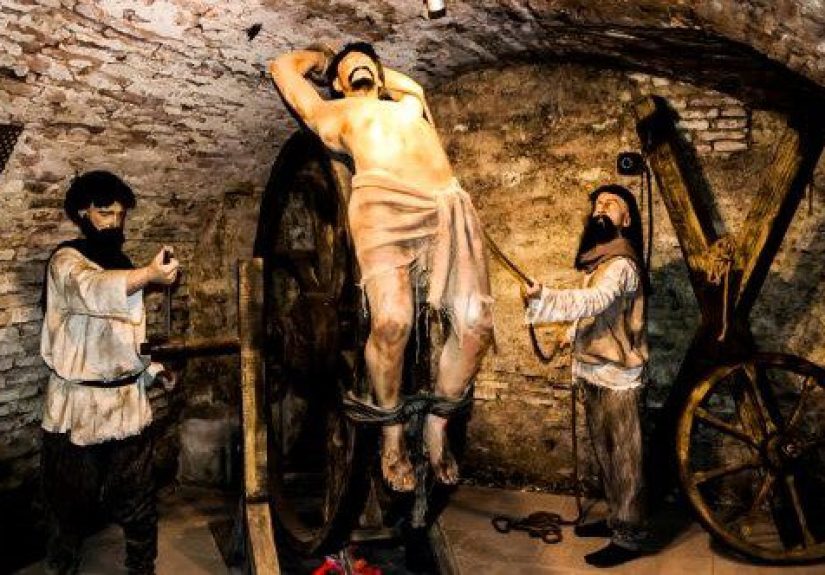

Executions used to be more than “a sentence carried out.” In many places and eras, they were public theaterpart warning label, part political messaging, part crowd event. That doesn’t make them any less tragic; it just makes them easier to understand as a tool of power. When leaders wanted obedience, they didn’t only punish the personthey staged the punishment to teach a lesson to everyone watching.

This list looks at ten men whose deaths became infamous. Some were executed for plots or rebellion. Others were executed because their ideas threatened a system built on conformity. And a few were executed amid intense controversy that still sparks debate today. In each case, the “horror” isn’t just the methodit’s the combination of fear, spectacle, politics, and irreversible finality.

Quick Table of Contents

- 1) Guy Fawkes

- 2) William Wallace

- 3) Jan Hus

- 4) Giordano Bruno

- 5) Sir Thomas More

- 6) William Tyndale

- 7) King Charles I

- 8) King Louis XVI

- 9) Maximilien Robespierre

- 10) John Brown

- Bonus: Sacco & Vanzetti and Julius Rosenberg (Why “modern” executions still haunt us)

- Reader Experiences: What These Stories Feel Like Up Close

1) Guy Fawkes (Executed 1606)

If you know the name Guy Fawkes, you probably know the mask, the bonfires, and the general vibe of “Remember, remember…” But behind the pop-culture afterlife is a real man involved in a real plot: the Gunpowder Plot of 1605, a plan to blow up the Houses of Parliament and kill King James I.

Fawkes was captured guarding gunpowder stored beneath Parliament. He was tried for high treason and sentenced to a punishment meant to make an example of traitors. Accounts indicate he died during the execution process, avoiding the full sentence as written. Even without the grisly details, the point is clear: the state wanted the public to see the cost of defying it.

Why his execution became “horrible” in history

Because it was designed to be unforgettable. The spectacle lived oneventually transforming into an annual commemoration that still echoes in modern culture, from fireworks to political symbolism.

2) William Wallace (Executed 1305)

William Wallace wasn’t just a warrior; he became a symbol. He fought against English control in Scotland during the First War of Scottish Independence. After years of resistance, he was captured in 1305, taken to London, and convicted of treason.

Wallace was sentenced under a medieval punishment reserved for traitorsone that combined humiliation, public display, and a deliberate sense of “this is what happens when you challenge the crown.” Modern summaries often call the execution brutal, but what matters most is the intention behind it: erase the man, frighten the movement.

The bigger lesson

Wallace’s death was meant to end a cause. Instead, it helped cement him as a national legendproof that executions can sometimes create the very martyrdom authorities were trying to prevent.

3) Jan Hus (Executed 1415)

Jan Hus was a Czech religious reformer whose critiques of church corruption and calls for reform put him on a collision course with the authorities of his time. He traveled to the Council of Constance with an expectation of safe conduct, but he was arrested, tried, and condemned for heresy.

Hus was executed in 1415. The horror in his story is the combination of political power and theological power working together: once labeled a threat, the outcome became less about debate and more about elimination.

Why his execution mattered

Hus’s death didn’t stop reform-minded ideasit inflamed them. His execution became a catalyst for unrest and conflict in Bohemia, showing how punishing an idea can be harder than punishing a person.

4) Giordano Bruno (Executed 1600)

Giordano Bruno’s life reads like a warning about being too intellectually loud in an age that demanded intellectual obedience. He explored philosophy and cosmology, argued about theology, and refused to neatly fit into acceptable boundaries. After years of legal and religious conflict, he was condemned as a heretic and executed in Rome in 1600.

Bruno’s execution is often discussed as part of the larger story of free thought versus institutional authority. Historians still debate which parts of his beliefs were most central to his condemnationhis theological positions, his philosophical arguments, or the way he challenged accepted doctrine. Either way, the message sent to the public was chillingly straightforward: some ideas are not allowed.

What makes it “horrible” beyond the method

It represents how a society can criminalize thoughtespecially when thought threatens the legitimacy of powerful institutions.

5) Sir Thomas More (Executed 1535)

Sir Thomas More was a celebrated English humanist and statesmanuntil politics and conscience collided. When Henry VIII broke with the Catholic Church and asserted royal supremacy over the Church of England, More refused to endorse it. That refusal became treason in the eyes of the state.

More was convicted and executed in 1535. His story is a sharp example of how governments can turn disagreement into disloyalty. When the law becomes a tool to demand public agreement, silence can be treated as rebellion.

Why this execution stuck in cultural memory

Because it’s not just about a beheadingit’s about an ethical line someone refused to cross, even when crossing it would have saved his life.

6) William Tyndale (Executed 1536)

William Tyndale is remembered for helping shape the English language through Bible translation. He translated scripture directly from Hebrew and Greek sources, producing work that would influence later English Bibles for generations.

But translation was never just a language project. In a Europe fractured by religious conflict, putting scripture into the hands of ordinary readers was politically explosive. Tyndale was condemned for heresy and executed in 1536 near Vilvoorde.

The grim irony

Authorities tried to stop his words. The words survivedprinted, copied, and absorbed into the DNA of English religious and literary history.

7) King Charles I (Executed 1649)

It’s one thing for a government to execute a rebel. It’s another thing for a government to execute a king. Charles I’s execution in 1649 was the culmination of civil war, political breakdown, and a profound conflict over who held ultimate authority in Britain.

After being tried and condemned, Charles I was publicly executed in London. Even today, it’s hard to overstate how shocking that was for a world accustomed to monarchy as an almost sacred institution. This wasn’t just a deathit was a declaration: the ruler could be judged by the ruled.

Why his execution felt especially “horrible” to contemporaries

Because it destabilized the entire idea of legitimacy. If a king could die by legal decree, what did that mean for every other throne in Europe?

8) King Louis XVI (Executed 1793)

Louis XVI became the human symbol of a collapsing system. During the French Revolution, the monarchy was abolished, and Louis was tried and convicted of treason. He was executed by guillotine on January 21, 1793, in Paris.

The guillotine was promoted as a “modern,” standardized methodfast, consistent, less dependent on the executioner’s skill. But the public nature of Revolutionary executions still carried the old logic: display the consequences, harden the new order, and prove the revolution meant business.

What made this execution infamous

It was a turning point. A nation didn’t just punish a man; it ended a centuries-old idea of monarchy with a single, irreversible act.

9) Maximilien Robespierre (Executed 1794)

Robespierre is one of history’s clearest examples of political gravity reversing directionfast. As a leading figure during the Reign of Terror, he helped shape a system where suspicion could be deadly. In 1794, the system turned on him. He was arrested and executed by guillotine on July 28, 1794.

Robespierre’s story is horrifying because it shows how violent political machinery can become self-consuming. When fear becomes policy, it rarely stays neatly aimed at “the enemy.” Eventually, the definition of enemy expands until it includes yesterday’s heroes.

The cautionary takeaway

Executions used as instruments of political cleansing tend to multiply. And once they multiply, nobody is truly safenot even the architects.

10) John Brown (Executed 1859)

John Brown believed slavery was a moral emergency that demanded action, not polite conversation. In 1859, he led a raid on the federal armory at Harpers Ferry, hoping to spark a larger uprising against slavery. The plan failed. Brown was tried for treason against Virginia (among other charges) and executed by hanging on December 2, 1859.

Brown’s execution horrified people for different reasons depending on where they stood. To some, he was a terrorist. To others, a martyr. What’s undeniable is that his death intensified national tension. It didn’t settle the argument; it sharpened ithelping push the United States closer to civil war.

Why his execution still resonates

Because it raises a hard question with no easy answers: when laws protect injustice, what does “justice” require?

Bonus: Sacco & Vanzetti and Julius Rosenberg (Why “modern” executions still haunt us)

You might notice that many of the most infamous executions happened centuries ago, when public punishment was openly theatrical. But the modern era has its own “horrible” executionshorrible not because they were medieval, but because they remain controversial, contested, and deeply tied to fear-driven politics.

Sacco and Vanzetti (Executed 1927)

Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were Italian-born anarchists convicted of murder during a time of intense anxiety about immigration and radical politics. Despite worldwide protests and decades of debate about the fairness of their trial, they were executed in Massachusetts on August 23, 1927.

The horror here is the possibility of injustice. Whether one believes they were guilty or not, their case became a cultural symbol of how prejudice and political fear can influence legal outcomes.

Julius Rosenberg (Executed 1953)

Julius Rosenberg (along with his wife, Ethel) was convicted of conspiracy to commit espionage during the Cold War and executed at Sing Sing on June 19, 1953. The case remains one of the most debated legal and moral controversies of the era, especially regarding proportional punishment and the political climate surrounding the trial.

Modern executions can be “horrible” in a different way: they often happen behind walls, but the arguments about fairness, evidence, and motive live for generations.

Reader Experiences: What These Stories Feel Like Up Close (About )

Even when you avoid graphic detail, the emotional weight of execution history can hit hardespecially when people encounter it in the real world. Museums, historic sites, court documents, and even old newspaper archives have a way of turning “a fact” into “a moment.” And that shift is where many readers say the experience becomes unsettling in the most memorable way.

1) The strange quiet of historical sites. Visitors often describe a surprising silence at places linked to executionsformer prison grounds, courthouse squares, or city landmarks that look ordinary until you learn what happened there. A patch of pavement becomes a story. A tourist photo spot becomes a moral question. The contrast is the point: society moves on, but the record doesn’t. When people learn that a king was executed outside a building that still stands, or that a prisoner died in a facility whose name they’ve heard in movies, history stops feeling “old” and starts feeling “close.”

2) The paperwork is the scariest part. Many readers report that the most chilling “experience” isn’t the execution methodit’s the calm language around it. Trial summaries, sentencing documents, and official notices often read like the state is ordering office supplies. That’s not a joke; it’s genuinely unsettling. Words like “hereby,” “sentence,” and “shall be” turn a human life into procedure. When you see how ordinary the language is, you understand how easily a society can normalize extreme outcomes.

3) You start noticing the politics of fear. In controversial casesespecially in the 1920s and 1950speople say they recognize a pattern: public anxiety gets translated into policy, and policy into punishment. Even if you don’t know every detail, the vibe is familiar. “The enemy is everywhere.” “We must be tough.” “We can’t look weak.” Readers often connect this to modern debates about criminal justice, national security, and the death penalty. It’s not just historyit’s a mirror.

4) The emotional whiplash of “hero” vs. “villain.” A huge part of the experience is discovering that the same executed person can be remembered in opposite ways. John Brown can look like a terrorist or a moral prophet depending on perspective. Robespierre can look like a defender of revolution or an avatar of political paranoia. This ambiguity frustrates some readers at firstbecause we love tidy storiesbut it also makes the past feel more honest. History rarely hands you a single label and walks away.

5) The takeaway most people don’t expect: empathy. Not “approval,” not “excuse-making”just the basic human recognition that an execution is always final, and that finality deserves seriousness. Many readers describe finishing these stories with a new awareness of how quickly power can harden, how easily crowds can be stirred, and how important fairness becomes when the consequences can’t be undone.

In other words: the “experience” of reading about horrible executions isn’t just learning how people died. It’s learning what societies were trying to say when they made death into a messageand asking whether we’ve truly stopped doing that.

Conclusion

These ten stories span centuries and continents, but they share a pattern: executions often reveal more about the society doing the killing than the individual being killed. Sometimes the goal was vengeance. Sometimes it was deterrence. Sometimes it was to silence an idea. And sometimes it was wrapped in legal language that looked orderly while producing something irreversible.

History can’t undo these deaths. But it can help us recognize the conditions that made them possible: fear, polarization, propaganda, scapegoating, and the temptation to treat punishment as performance. If there’s a lasting lesson here, it’s that justice is not just about outcomesit’s about process, restraint, and the humility to admit that power can be wrong.