Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What is a composite character, exactly?

- 12 figures from historical movies who are composites of multiple people

- 1) Itzhak Stern Schindler’s List (1993)

- 2) Carl Hanratty Catch Me If You Can (2002)

- 3) Captain Virgil Hilts (“The Cooler King”) The Great Escape (1963)

- 4) Peter Brand Moneyball (2011)

- 5) Alan Isaacman (as portrayed) The People vs. Larry Flynt (1996)

- 6) Ken Mattingly (as used in the film’s problem-solving arc) Apollo 13 (1995)

- 7) Commander Bolton Dunkirk (2017)

- 8) Rayon (and Dr. Eve Saks) Dallas Buyers Club (2013)

- 9) C.W. Moss Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

- 10) Bobby Ciaro Hoffa (1992)

- 11) Micky Rosa 21 (2008)

- 12) Curt Wild Velvet Goldmine (1998)

- How to spot a composite character while you’re watching

- Is using composites “wrong”?

- of viewing experiences: what composites feel like in real life

- Conclusion

Historical movies have a weird job: they’re supposed to teach you something, make you feel something, and do it all before you finish your popcorn.

Real history, unfortunately, does not come with tidy three-act structure, one-liner-ready villains, or a convenient “best friend” who explains the whole plot

while the hero stares meaningfully into the middle distance.

That’s where the composite character comes inthe cinematic equivalent of a “group project” where one person turns in the final paper.

Filmmakers blend multiple real people into a single character to streamline a crowded story, protect privacy, avoid defamation headaches, or simply keep you

from needing a flowchart and three intermissions.

Below are 12 figures from historical (and history-adjacent) films who look like one person on screenbut are actually built from multiple real people.

Sometimes they carry a real name with expanded actions; sometimes they’re fictional “stand-ins” who represent a whole team. Either way, once you notice the

trick, you’ll start spotting it everywherelike continuity errors, but with better tailoring.

What is a composite character, exactly?

A composite character is a single on-screen figure created by combining traits, experiences, and actions of multiple real people (or multiple documented

roles) into one. In “based on a true story” films, this is often done to compress timelines, simplify institutions (like the military, NASA, or courts),

and keep audiences emotionally anchored to a manageable cast.

The upside: cleaner storytelling, clearer stakes, and fewer “Wait, who is that again?” whispers. The downside: real individuals can get erased, credit can

shift, and audiences may mistake a convenient narrative shortcut for literal truth. The goal isn’t always deceptionit’s often readability. But it’s still

worth knowing when a movie is using a highlight reel instead of the full game tape.

12 figures from historical movies who are composites of multiple people

1) Itzhak Stern Schindler’s List (1993)

On screen, Itzhak Stern is Oskar Schindler’s steady moral counterweight: the person who helps translate Schindler’s ambition into lifesaving action.

Historically, the film’s Stern blends roles associated with multiple people involved in Schindler’s operations and the wider rescue effort. The result is a

single character who embodies the administrative brilliance, courage, and moral pressure that came from more than one real-world figure.

The storytelling purpose is clear: instead of introducing several key organizers (each with overlapping responsibilities), the film gives viewers one

consistent relationshipSchindler and “Stern”to carry the emotional weight and ethical arc.

2) Carl Hanratty Catch Me If You Can (2002)

Carl Hanratty is the relentless FBI agent chasing Frank Abagnale Jr.part Javert, part exhausted father figure, part “I can’t believe this kid again.”

In reality, the pursuit involved multiple investigators across agencies and jurisdictions. Hanratty is written as an amalgam, shaped especially by the

dynamic Abagnale described with agent Joseph Shea, but not limited to one person’s exact biography.

The film’s emotional engine depends on the chase becoming personal. A rotating cast of real officers would be accurate, but it would also feel like a

customer service handoff: “Hello, I’ll be your new pursuer today.”

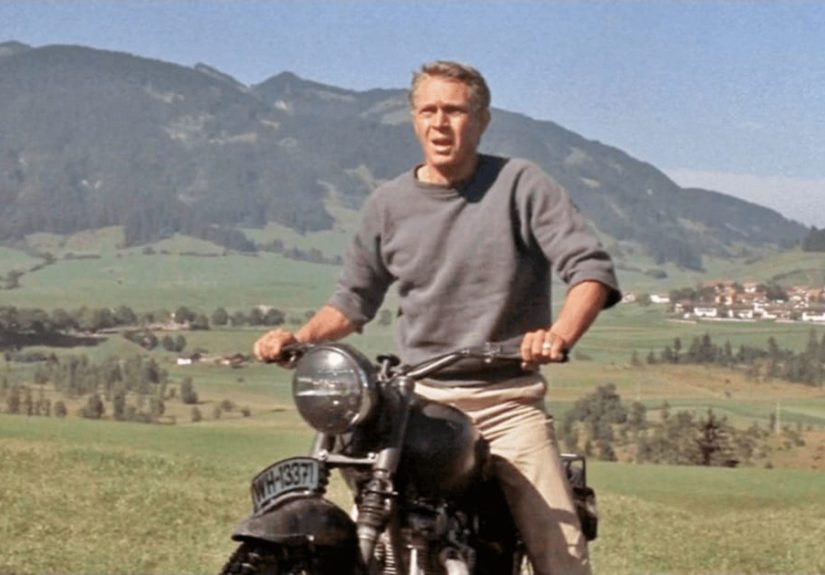

3) Captain Virgil Hilts (“The Cooler King”) The Great Escape (1963)

Hilts is the movie’s iconic escape artistcool under pressure, endlessly inventive, and seemingly born with a contraband baseball glove.

The historical escape from Stalag Luft III involved many prisoners with different specialties and repeated attempts. Hilts is commonly described as drawing

from multiple real escape-minded POWs rather than mapping cleanly onto a single man’s exact actions.

It’s a classic war-movie move: focus the “spirit” of a group into one memorable face, so audiences feel the risk and persistence without tracking a dozen

separate backstories.

4) Peter Brand Moneyball (2011)

Peter Brand is the young analytics wizard who helps Billy Beane remake the Oakland A’squietly brilliant, statistically fearless, and allergic to baseball

tradition (in the most polite way possible). Brand is fictional, inspired by Paul DePodesta, but also described as a composite representing multiple

assistants and the broader front-office shift toward data-driven decision-making.

In other words, Brand isn’t just “one guy.” He’s a narrative shortcut for a revolution: spreadsheets, debates, scouting conflicts, and the organizational

pushback that wouldn’t fit neatly into one real person’s daily calendar.

5) Alan Isaacman (as portrayed) The People vs. Larry Flynt (1996)

Alan Isaacman was a real attorney for Larry Flynt and argued a major free-speech case involving Hustler. The film, however, presents Isaacman as the

primary legal partner through events that involved multiple lawyers and assistants. One particularly notable example: the movie depicts Isaacman being

wounded during the 1978 shooting of Flynt, but that injury happened to another attorney, Gene Reeves Jr.

Courtroom stories are catnip for composites: legal work is collaborative, but movies like to give the audience one clear advocate to follow from first

filing to final verdict.

6) Ken Mattingly (as used in the film’s problem-solving arc) Apollo 13 (1995)

Ken Mattingly was absolutely real, and the key setup is true: he was removed from the mission close to launch after exposure concerns and then helped from

the ground. The film emphasizes Mattingly’s role in solving crucial technical challenges, but accounts of the real operation describe a far larger team of

astronauts and engineers contributing to the solutions shown.

This is a “composite-by-emphasis” approach: the character exists, but the movie concentrates distributed teamwork into a single, emotionally satisfying

problem-solving threadbecause watching 37 people pass checklists around doesn’t hit the same as one face racing the clock.

7) Commander Bolton Dunkirk (2017)

Kenneth Branagh’s Commander Bolton is the calm, watchful naval officer overseeing the evacuation from the beachpart coordinator, part conscience, part “the

grown-up in the room.” The character is described as a composite of several real men involved in the Dunkirk evacuation, folding multiple leadership and

logistical roles into one steady presence.

The movie’s structure is already complex (multiple timelines, shifting viewpoints). A composite commander gives viewers one stable anchor on the sand while

the film crosscuts between sea, air, and shore.

8) Rayon (and Dr. Eve Saks) Dallas Buyers Club (2013)

Rayon is the film’s emotional lightning rod: charismatic, fragile, funny, and devastatingly human. The character is presented alongside Dr. Eve Saks as a

fictional supporting figure built from interviews and experiences of multiple peoplepatients, activists, and medical perspectivesrather than one

documented individual with a single traceable biography.

The movie is telling a broader story about desperation, access, stigma, and a messy medical moment. Composites here function less like “name swaps” and

more like a collagemeant to reflect many lived experiences through one relationship the audience can actually hold onto.

9) C.W. Moss Bonnie and Clyde (1967)

C.W. Moss joins the Barrow gang as the eager, sometimes bumbling tagalong who gives the story both volatility and a kind of tragic innocence.

Historically, the gang included associates with different roles and timelines. The film’s C.W. Moss is portrayed as a composite drawing from more than one

real gang affiliate, blending traits and circumstances so the audience can track “the young recruit” as a single character rather than a changing roster.

Crime stories frequently do this because the real networks around famous outlaws are bigger (and messier) than any single screenplay wants to admit.

10) Bobby Ciaro Hoffa (1992)

Bobby Ciaro is Jimmy Hoffa’s loyal companion and fixeralways nearby, always invested, and always carrying the emotional weight of “the inner circle.”

The character is widely described as a fictional composite based primarily (though not exclusively) on real Hoffa associates, collapsing multiple roles

into one on-screen shadow.

The biopic problem is simple: real power operates through many relationships. Movies compress that complexity into a single confidant so the protagonist

has someone to talk to besides a wall of microphones.

11) Micky Rosa 21 (2008)

Micky Rosa is the brilliant, intense professor who recruits students into blackjack card countingpart mentor, part boss, part “welcome to your new life.”

The real MIT blackjack story involved multiple leaders with different styles and eras. Rosa is presented as a composite of several figures associated with

the real team’s leadership and methods, creating one recognizable architect of the operation for the film.

Whether you love or hate the movie’s changes, the composite approach makes one thing very watchable: you know exactly who is driving the bus, even when the

bus is speeding straight toward consequences.

12) Curt Wild Velvet Goldmine (1998)

Curt Wild is a glam-era punk meteordangerous, magnetic, and impossible to ignore. The film plays as a mythic remix of rock history, and Curt Wild is

described as an amalgam drawing heavily from figures like Iggy Pop and Lou Reed, with additional echoes of the broader scene and its personalities.

In a movie that’s deliberately stylized and dreamlike, the composite character isn’t a cheatit’s the point. Curt Wild isn’t meant to be a Wikipedia page.

He’s meant to feel like the sound of an era: messy, brilliant, and a little bit on fire.

How to spot a composite character while you’re watching

- They’re everywhere at once: One character attends meetings, fights battles, makes discoveries, and delivers emotional speeches that would normally require a committee.

- They’re the “translator”: They explain complex systems (law, science, war logistics) in digestible dialogueoften to the protagonist, but really to you.

- They’re the emotional bridge: They connect the hero to “the people affected,” standing in for many real individuals’ experiences.

- They have suspiciously perfect timing: They show up right when the story needs a turning point, even if history was slower and messier.

Is using composites “wrong”?

Not automatically. Sometimes composites are responsible storytelling: they protect private individuals, reduce confusion, and keep a film from turning into a

nine-hour docuseries with a cast list longer than the credits. But there’s a fair critique, too: composites can unintentionally steal credit, reshape blame,

and simplify systemic forces into a few dramatic personalities.

A healthy rule: treat movies as a gateway drug to history, not the final prescription. If a character moved you, that’s a great reason to learn who (plural)

they might represent.

of viewing experiences: what composites feel like in real life

Watching a historical movie with even one “history friend” in the room is a special kind of sport. The film starts, everyone’s happy, and thenabout

22 minutes insomeone pauses and says, “Okay, that guy didn’t do all of that. That’s, like, three guys.” This is usually followed by a gentle spiral into

Google searches, whispered debates about dates, and the inevitable comment: “I love the movie, but…”

Composites are often the reason those debates happen. They’re also the reason the movie works. A film has to build momentum; real life builds paperwork.

When a movie compresses five administrators into one commander, you feel the pressure on a single face. When it compresses a team of analysts into one

young statistician, you can track the human conflicttradition versus changewithout needing a whiteboard.

There’s also a funny emotional whiplash the first time you learn a beloved character is a narrative blend. You’re not “tricked,” exactly, but you do feel

like you’ve been introduced to someone who doesn’t existlike realizing your favorite band’s “lead singer” is actually a rotating committee of four people

in the recording studio. The feelings were real; the résumé was curated.

In classroom settings (or any environment where someone can’t resist turning movie night into a seminar), composites become teachable moments. They prompt

better questions than “Is it accurate?” Instead you ask, “What did the filmmakers prioritize?” If the answer is clarity, the composite might be doing an

honest job: representing a broader truth about how institutions function, or how movements are built by many hands. If the answer is drama, you might

notice the composite absorbing heroismor villainythat belonged to a larger system.

The most satisfying experience is when a movie sends you down a research rabbit hole and you come back with a richer understanding than the film alone

could offer. You learn the names behind the “Stern” role. You discover how many people contributed to the Apollo 13 solutions. You realize the “mentor”

figure in a gambling story represents multiple leaders across different eras. Suddenly the composite character becomes a signpost: a reminder that history is

almost always collective, even when the movie wants a single person to hold the spotlight.

And honestly? Once you start spotting composites, you become a sharper viewer. You watch the story and the storytelling at the same time. You enjoy the film

as a filmthen use it as a map to the real people who made the history happen.

Conclusion

Composite characters are one of Hollywood’s most common “true story” tools: they make complicated history watchable by turning many voices into one.

Sometimes that’s an elegant shortcut; sometimes it’s a distortion worth questioning. Either way, knowing the trick helps you enjoy historical movies with

your eyes openand your curiosity switched on.