Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- When Visiting an Asylum Was a Respectable Day Out

- Why 19th-Century Tourists Flocked to Mental Asylums

- What Tourists Actually Saw Inside 19th-Century Asylums

- The View from the Inside: How Patients Experienced Asylum Tourism

- Could Asylum Tourism Have Any “Benefits”?

- Why the Theme-Park Atmosphere Eventually Faded

- From Victorian Day Trip to Modern Dark Tourism

- Experiences and Thought Experiments: Walking Through a 19th-Century Asylum

- Conclusion: What 19th-Century Asylum Tourism Says About Us

If you could time-travel back to the 19th century, your souvenir selfie might not be in front of a famous cathedral or a scenic waterfall.

Instead, you might find yourself strolling through the landscaped grounds of a state-of-the-art mental asylum,

politely peeking into wards while a superintendent proudly explains his “scientific” methods. For many middle-class travelers,

asylum tourism was a perfectly respectable day trip, advertised almost like a visit to a zoo, museum, orby our standardsa very dark theme park.

The idea feels shocking today, but it made sense in the context of the time. Asylums were marketed as modern, hopeful places filled with light,

air, and moral reform. Visitors weren’t just there to gawk (although many clearly did); they came for education, entertainment, and reassurance

that society was dealing with “madness” in an orderly, humane way. This article explores why 19th-century tourists visited mental asylums,

what they actually saw, how patients experienced this unwanted attention, and how the whole phenomenon shaped modern attitudes toward mental health.

When Visiting an Asylum Was a Respectable Day Out

By the early 1800s, many countries in Europe and North America were building new, purpose-designed psychiatric hospitals to replace

chaotic city madhouses and workhouses. Reformers argued that people with mental illness needed clean environments, fresh air, and

structurenot chains and filth. Large public asylums, often located on hills outside cities, became symbols of modern medicine and

state responsibility.

At the same time, the 19th century saw an explosion in leisure travel. Railways made it easier for middle-class families to take

day trips, and guidebooks encouraged them to visit factories, prisons, and hospitals as part of an “educational” itinerary.

Touring institutions became a way to see the machinery of progress up close. Asylums were folded into that mix: a curious blend of

science lesson, social commentary, and slightly morbid entertainment.

Many hospitals actually welcomed visitors. Administrators believed that opening their doors would reassure the public that these

new institutions were clean, orderly, and not the horror shows people feared. Some asylums scheduled regular visiting hours,

especially on Sundays, when the middle classes were free to promenade through the grounds in their best clothes.

Why 19th-Century Tourists Flocked to Mental Asylums

Curiosity and the Pull of the “Other”

Let’s be honest: a big part of the draw was curiosity. To Victorian tourists, the asylum promised a safe way to get close to something

they found frightening and fascinatingmental illnesswithout ever being truly threatened by it. Newspaper accounts and travel writing

describe visitors watching patients from a distance, swapping whispered comments about their behavior the way you might today after a

particularly intense episode of a true-crime podcast.

In some earlier institutions, especially private madhouses, spectators literally paid admission to watch people with mental illness,

in scenes that sounded disturbingly like a human zoo. Later 19th-century “reformed” asylums were more controlled and respectable,

but the interest in seeing “the insane” up close never entirely went away.

Faith in Science, Progress, and Moral Reform

At the same time, there was a genuine belief that visiting an asylum was morally improving. Psychiatry was still in its infancy,

but doctors promoted asylums as laboratories of the minda place where cutting-edge treatment and careful management could transform

chaos into calm. Middle-class visitors were told that these institutions were curing people who would otherwise be chained in garrets

or paraded on the streets.

Touring an asylum let visitors see this supposed progress with their own eyes. They could walk along spotless corridors,

observe patients engaged in quiet activities, and leave convinced that modern medicine and benevolent government were making the world

a safer, more rational place. In a culture obsessed with self-control and respectability, watching “disorder” being domesticated was

oddly reassuring.

Architecture and Landscaped Grounds as Attractions

These institutions also looked impressive. Many 19th-century asylums were built on grand scales, with symmetrical facades,

high ceilings, and carefully designed gardens. Architects and reformers believed that beautiful surroundings could soothe troubled minds.

The buildings were often described in language you would expect for country estates or resort hotels: airy, harmonious, and uplifting.

For visitors, that meant plenty of picturesque views and good walking paths. Guidebooks sometimes noted the asylum’s architecture or

gardens as sights in their own right. Some sites were so scenic that tourists could easily forget they were strolling through a place of

confinementuntil a barred window or a locked door snapped them back to reality.

Charity, Morality, and Social Signaling

Visiting an asylum also allowed people to perform compassion. Tourists might bring small gifts, donate money, or praise the staff

for their “humane” treatment. These gestures reassured visitors that they were kind, modern, and on the right side of history.

Of course, there was often a strong dose of class and moral judgment mixed in. Many patients were poor, marginalized, or simply

didn’t fit social norms. For some visitors, the asylum affirmed a comforting hierarchy: the sane looking after the “insane,”

the respectable observing those who had lost their place in polite society.

What Tourists Actually Saw Inside 19th-Century Asylums

Guided Tours Through the Wards

A typical visit might begin with a warm welcome from the superintendent or a senior nurse, followed by a guided walk through selected areas.

Visitors might see dining halls, workshops, dormitories, and perhaps a chapel or recreation room. Staff often chose the calmest wards and

most presentable patients for these toursthink “best behavior only.”

Descriptions from the time mention orderly rows of beds, patients quietly sewing or reading, and large day rooms with pianos and games.

Tourists were meant to leave impressed by discipline and cleanliness, not traumatized by restraint or overcrowding (although both were

common behind the scenes in many institutions).

Patients as Unwilling Performers

Even when there were no explicit “shows,” visitors inevitably treated patients like exhibits. Some wrote about particular individuals

whose delusions or behaviors seemed especially dramatic. Others commented on how “normal” many patients looked, expressing surprise that

people who seemed so ordinary could be locked away.

In some places, patients gave musical performances or displayed crafts they had made in occupational therapy workshops.

These activities were partly therapeutic and partly public relations: they reassured visitors that the asylum was busy, productive,

and not a mere human warehouse.

The Sanitized Version Versus Harsh Reality

It’s important to remember that tourists usually saw the curated version. Many 19th-century asylums were severely overcrowded,

understaffed, and underfunded. Patients might endure physical restraints, isolation, or experimental treatments that ranged from

misguided to outright abusive.

Reformers and investigative journalists occasionally used their visits to expose these harsh realities. In some cases,

they reported filth, neglect, or cruel discipline that administrators had tried to hide. So while tourism could be a form of

voyeurism, it also sometimes provided outsiders with glimpses of conditions that needed urgent change.

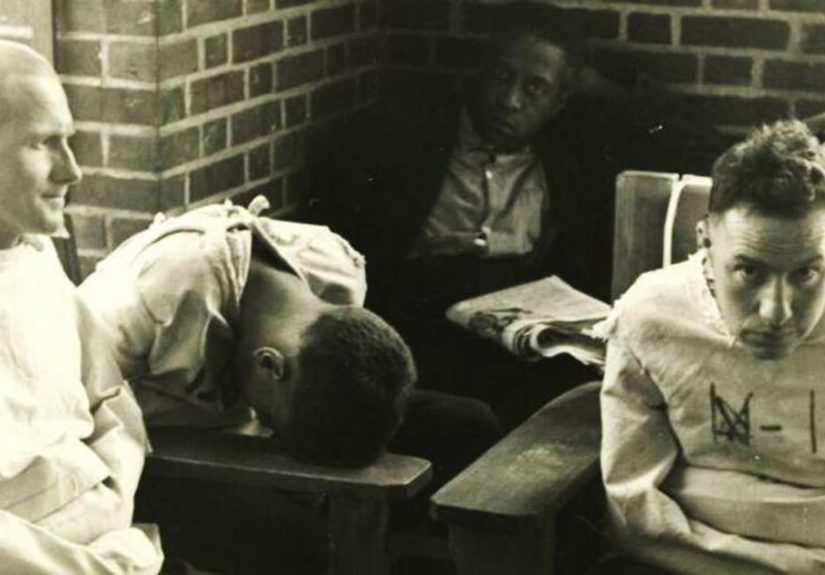

The View from the Inside: How Patients Experienced Asylum Tourism

Unsurprisingly, many patients did not enjoy being part of a tourist attraction. Accounts from former patients and sympathetic staff

describe visits as intrusive, humiliating, and dehumanizing. Imagine trying to recover from a serious mental health crisis while

strangers file past your bed, whispering and staring.

Some patients tried to ignore visitors; others reacted with agitation or distress. A few used the opportunity to plead their cases,

insisting they were wrongly confined or begging for help in contacting family or lawyers. For them, tourists were not harmless observers

but potential lifelinesor at least witnesses who might tell the outside world what really went on behind closed doors.

Over time, criticism of these visits grew. Reformers argued that if asylums were truly meant to be therapeutic, patients needed privacy

and stability, not constant exposure to strangers treating them like curiosities. By the late 19th and early 20th centuries,

professional ethics and new privacy standards began to push open-house tourism out of fashion.

Could Asylum Tourism Have Any “Benefits”?

It might feel wrong to talk about benefits when people were being treated as exhibits, but historically, the picture is complicated.

Opening asylums to the public allowed some visitors to see people with mental illness not as monsters but as human beings who laughed,

worked, and suffered like anyone else. For a few, that exposure chipped away at stigma.

Public access also created opportunities for scrutiny. Reporters, reformers, and visiting physicians didn’t always accept the official tour

at face value. They sometimes noticed overcrowding, underfeeding, or harsh discipline and used their observations to push for change.

Later investigative workincluding famous exposés of asylum abusesbuilt on this tradition of outsiders walking the wards and asking

uncomfortable questions.

Finally, tourism helped secure funding and political support. When wealthy donors or influential citizens visited a well-run asylum,

they were more likely to back expansions, new buildings, or improved staff training. That doesn’t erase the ethical issues,

but it shows how intertwined spectacle and reform could be.

Why the Theme-Park Atmosphere Eventually Faded

Several forces combined to make asylum tourism less acceptable over time. Psychiatry professionalized, and doctors increasingly emphasized

confidentiality and therapeutic environments. New laws and regulations restricted public access to patients’ lives, reflecting broader

changes in medical ethics.

At the same time, the public image of asylums shifted. As overcrowding and neglect worsened, these institutions looked less like uplifting

monuments to progress and more like embarrassing failures. By the mid-20th century, many large state hospitals were synonymous with

cruelty and warehousing. They were not places respectable tourists wanted to be seen touring anymore.

Deinstitutionalization in the later 20th century emptied many of these buildings. Some were demolished; others became offices, apartments,

or museums. The tourism didn’t stop, exactlyit just changed shape, turning into ghost tours, historical exhibits, and online photo essays

about “abandoned asylums.”

From Victorian Day Trip to Modern Dark Tourism

Today, you can still visit many former asylums, especially in Europe and North America. Some operate as museums dedicated to the history

of psychiatry; others appear in travel blogs as eerie ruins perfect for urban explorers and amateur photographers. This modern form of

dark tourism is different from 19th-century asylum visits, but it raises similar questions.

Are we learning from history, or just consuming other people’s suffering as entertainment? When we walk through crumbling wards or pose

for photos under peeling paint, do we remember the individuals who lived and died theretheir fears, hopes, and moments of joy?

Or are they still being reduced to background scenery in someone else’s story?

A more ethical approach is possible. Good museums and tours explain both the ideals and the failures of historical mental health care,

foregrounding patient voices wherever possible. They remind visitors that what once looked like enlightened reform often contained serious

blind spotsand that our current systems will almost certainly look flawed to future generations, too.

Experiences and Thought Experiments: Walking Through a 19th-Century Asylum

To understand the strange mix of curiosity, hope, and harm that defined asylum tourism, it helps to imagine what a visit may have felt like.

Picture yourself as a respectable 19th-century travelera schoolteacher, perhaps, or a merchant passing through town on business.

Your guidebook lists the local asylum as a recommended attraction: “A model institution, well worth a visit for those interested in

the latest advances in moral treatment.” Intrigued, you take a carriage ride out of town. The building appears on a hill,

framed by trees and broad lawns. It looks less like a prison and more like a grand country estate.

At the gate, you sign a visitor book in looping script. The superintendent greets you warmlypublic opinion matters to him, after all.

He leads your small group along wide corridors, pointing out high windows, ventilation systems, and bright day rooms.

You nod in approval; everything seems orderly, almost peaceful.

As you pass one ward, patients look up from their sewing or card games. Some avoid your gaze. Others stare directly at you with expressions

that are hard to readcuriosity, resentment, confusion, or maybe just boredom. You shift uncomfortably but reassure yourself:

the doctor said they are better off here than on the streets.

In the dining hall, you admire the long tables laid out with simple, decent meals. “We believe in regularity and wholesome food,”

the superintendent explains. In the workshop, you watch patients making shoes or weaving baskets. Your guide praises the moral value

of productive labor; you are impressed by how calm everyone appears.

Then something disrupts the script. A woman in a corner begins to cry and call out for her children.

A male patient approaches your group, insisting he has been wrongfully confined and begging you to speak to a magistrate on his behalf.

Staff step in gently but firmly, guiding him away. The tour moves on. You tell yourself you have just witnessed symptoms of illness,

not evidence of injustice. Still, the encounter lingers in your mind during the carriage ride back to town.

Now, fast-forward to the present and imagine walking through the same building as a 21st-century visitor.

The lawns are overgrown, the windows boarded up or broken. Your guide is a local historian or museum curator,

not a superintendent. They tell stories about overcrowded wards, underfunded staff, and treatments that ranged from rational

but ineffective to actively harmful.

In a former dormitory, panels display photographs of patients and excerpts from case files. One is the woman who cried for her children.

Another is the man who begged visitors to believe his story. You realize that 19th-century tourists walked past these same people,

sometimes with sympathy, sometimes with morbid curiosity, but rarely with true understanding.

Standing in the quiet, you feel a mix of emotionssadness, anger, and maybe a hint of guilt, even though you were born long after

these events. It’s the uneasy awareness that our desire to look at suffering is still with us, even when we call it education,

history, or “dark tourism.” The challenge is to turn that gaze into something more responsible: a prompt to support humane mental health care

today, rather than just another thrill.

Conclusion: What 19th-Century Asylum Tourism Says About Us

The fact that 19th-century tourists visited mental asylums like theme parks tells us as much about the visitors as it does about the institutions.

They wanted reassurance that science and government were managing the problems that frightened them. They wanted to feel compassionate without

surrendering their sense of superiority. And, yes, they wanted a little shock and drama to brighten an otherwise ordinary Sunday.

From our perspective, the whole practice looks deeply unethical. Yet it also helped expose abuses, raise funds, andoccasionallyhumanize people

who had long been dismissed as hopeless or dangerous. As with many parts of history, asylum tourism is a tangled mix of progress and harm,

idealism and exploitation.

Today, when we visit former asylums, share photos of abandoned wards, or binge-watch shows about psychiatric institutions,

we’re still grappling with the same questions. Are we using these stories to better understand mental health and advocate for

compassionate careor just to entertain ourselves? If nothing else, the history of asylum tourism should make us a little more thoughtful

about how we look at other people’s pain, past and present.

![23 Sales Email Templates With 60% or Higher Open Rates [+ Bonus Templates]](https://2quotes.net/wp-content/uploads/2026/03/23-sales-email-templates-with-60-or-higher-open-rates-bonus-templates-6ws5F7Yp-thumb.jpg)