Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What the Cornell Cup Is (and why it’s a big deal)

- The 2019 winners at a glance

- First Place: S.S. MAPR an autonomous boat that treats rivers like a lab

- Second Place: TerraNova a leaping rover designed for lunar caves

- Third Place: FWMAV (Quadflappers) a drone that chose flapping wings over propellers

- People’s Choice: Vulcan IoT sensors aimed at early wildfire risk detection

- The bigger takeaway: movement gets attention, but embedded systems do the real work

- How to borrow inspiration from these projects (without copying them)

- Real-world experiences from building Cornell Cup-style robots (extra)

- Conclusion

- SEO tags (JSON)

If you want a snapshot of where engineering brains were headed in 2019, you could do worse than watching the Cornell Cup finals.

In one weekend, student teams rolled out a robot boat that treats a river like a moving laboratory, a drone that ditched propellers

for flapping wings, and a rover that can hop its way into places wheels usually fear to tread (like the entrances to lunar caves).

The charm of the Cornell Cup is that it rewards what real-world engineering actually demands: a clear problem, a working prototype,

and a credible story about how the tech would survive outside a slideshow. The 2019 winners nailed that formulawhile also proving

that “embedded systems” doesn’t have to mean “embedded boredom.”

What the Cornell Cup Is (and why it’s a big deal)

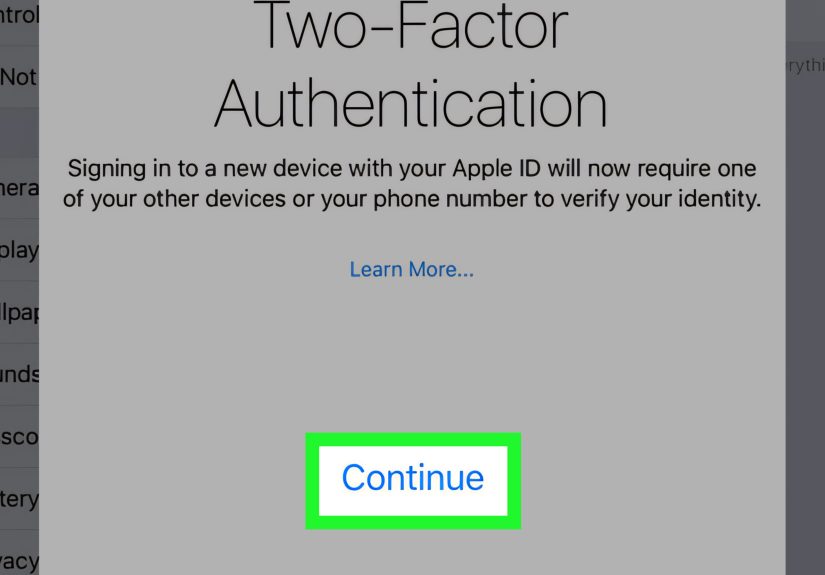

The Cornell Cup is an embedded design competition for college teams, built around one simple idea: give students an excuse (and a deadline)

to turn ambitious prototypes into something you can demo to judges and the public. The finals format pushes teams to do two different kinds of

communication well: hands-on demonstration at an expo booth and a formal presentation that explains the engineering choices and tradeoffs.

In 2019, finalists brought their projects to the NASA Kennedy Space Center Visitor Center in Florida for the final eventan appropriately dramatic

setting for anyone trying to convince a panel of judges that their robot belongs in the world. Rockets in the background are basically the ultimate

“no pressure” environment.

The 2019 winners at a glance

- First Place: S.S. MAPR an autonomous surface vehicle that measures water quality and collects samples at different depths.

- Second Place: TerraNova a leaping rover concept designed to explore lunar caves.

- Third Place: FWMAV (Quadflappers) a flapping-wing micro air vehicle that swaps rotors for ornithopter-style wings.

- People’s Choice: Vulcan IoT a sensor-network concept aimed at spotting wildfire risk early using environmental data.

First Place: S.S. MAPR an autonomous boat that treats rivers like a lab

The real-world problem: water data is precious, and rivers don’t wait

Rivers are dynamic systems: temperature changes, runoff spikes after storms, pollution events happen fast, and conditions can shift significantly

from one stretch of water to the next. Traditional samplingsending people out with handheld instruments and grab bottlesworks, but it’s slow,

labor-intensive, and doesn’t scale well if you want frequent measurements across a wide area.

S.S. MAPR attacked that gap with an autonomous surface vehicle (ASV) designed to gather water quality measurements and collect samples at varying

depths. In other words: the team didn’t just build a robot boat. They built a “field technician” that can be deployed repeatedly without needing a

full expedition every time.

What it did (and why that matters)

The S.S. MAPR concept focused on two things resource managers care about: reliable measurements and repeatable sampling. The boat was designed to

measure water quality metrics like dissolved oxygen and temperature, and it included a sampling mechanism capable of pumping water from selected

depthsso users could capture data (and samples) that reflect what’s happening below the surface, not just at the top.

That “varying depths” detail is easy to skim past, but it’s a big deal. Water conditions can stratify, especially in slower sections or where

temperature and flow differ. A system that can measure and sample at multiple depths gives a much more truthful picture of a waterway.

A quick, practical sidebar: why dissolved oxygen keeps showing up in water-tech projects

Dissolved oxygen (DO) is one of the most useful “at a glance” indicators of aquatic health. When DO drops too low, fish and other organisms can get

stressed or die off, and low oxygen often signals other problems (like too much organic matter decaying in the water, which consumes oxygen).

Engineers love DO because it’s measurable, comparable over time, and directly connected to real outcomes. In other words, it’s the kind of number

that turns a robotics demo into something a city, watershed group, or environmental agency can actually use.

Why S.S. MAPR won: a strong “systems story”

The best embedded projects aren’t just cleverthey’re coherent. S.S. MAPR had a complete loop:

(1) autonomous movement to cover more ground, (2) sensing and sampling to gather credible information, and (3) a use case that’s easy to explain:

help monitor waterways efficiently and respond faster when conditions change.

It’s the kind of project that makes judges think, “Yes, this could leave the lab,” which is basically the highest compliment in applied engineering.

Second Place: TerraNova a leaping rover designed for lunar caves

Why lunar caves are worth the hassle

Lunar pits and cavesoften discussed in the context of lava tubesare fascinating because they may offer more stable temperatures and protection from

hazards like radiation and micrometeorites compared with the exposed lunar surface. That makes caves interesting targets for future exploration and,

potentially, future habitation concepts.

But “interesting” does not mean “easy.” Caves are exactly the kind of terrain that punishes conventional rover designs: steep entrances, broken rock,

unpredictable geometry, and limited lighting. Wheels are greatuntil they aren’t.

The TerraNova idea: when wheels aren’t enough, add a jump

TerraNova earned second place with a rover concept built around a jumping (or hopping) mechanism aimed at handling rubble-filled cave entrances.

The point wasn’t to do parkour for fun (though, admittedly, it’s excellent marketing). The point was mobility: if a rover can hop over obstacles that

stop a wheeled vehicle, it can access environments that have been effectively off-limits.

A leaping rover also changes how you think about navigation. Instead of continuously rolling, you’re planning discrete “moves” where the rover must

land safely, recover its orientation, and build a map from partial views. It’s a harder control problem, but it’s also a powerful way to expand what

robotic exploration can reach.

Engineering tradeoffs: mobility, energy, and reliability

Hopping sounds simple until you remember physics is undefeated. Every jump costs energy, every landing introduces impact forces, and the rover has to

avoid turning into a very expensive paperweight after a bad bounce. So the design challenge becomes a balancing act:

- Energy budget: Can the rover hop enough times to do meaningful work?

- Landing stability: Can it land without tipping or damaging itself?

- Sensing and mapping: Can it build a usable model of the environment in low-light, occluded spaces?

- Mechanical durability: Can the mechanism survive repeated impacts?

TerraNova stood out because it treated lunar-cave exploration as a full mission problem, not a gimmickmobility was the enabling technology for a

genuinely challenging environment.

Third Place: FWMAV (Quadflappers) a drone that chose flapping wings over propellers

Bio-inspired flight, with an engineering twist

The Flapping-Wing Micro Air Vehicle (FWMAV), built by students at the University of California, Irvine, grabbed third place by doing something that

immediately makes people lean forward: it looked like a quadcopter, but the propellers were replaced with flapping wings. Instead of the familiar

“whirrrr,” you get a mechanical rhythm that feels more like a tiny robotic birdexcept with the stubborn determination of a machine that refuses to

be poetic on command.

Why flapping wings are interesting (and difficult)

Flapping-wing flight is attractive because it hints at capabilities nature already solved: agile maneuvering at small scales, potentially different

efficiency characteristics, and a form factor that could be useful in constrained environments. But it’s hard because the forces are oscillatory and

coupledmeaning the same motion that creates lift can also create vibrations and control challenges.

A traditional quadcopter gets to rely on smooth thrust and well-understood control models. A flapping system has to deal with repeating motion cycles,

mechanical tolerances, and rapid changes in aerodynamic forces. It’s like trying to write neat handwriting while someone gently shakes your elbow

several times per second.

Why FWMAV placed: it made an ambitious concept demo-worthy

Plenty of student projects have big ideas. FWMAV stood out because it turned a big idea into a presentable system: a recognizable platform (quadcopter

layout) paired with an unconventional propulsion method (ornithopter-style wings). It was a strong example of how to innovate without making your

whole design impossible to test.

People’s Choice: Vulcan IoT sensors aimed at early wildfire risk detection

Wildfires don’t need your calendar invite

Wildfire risk can change quickly with weather, dryness, and local conditions. In the real world, early detection and situational awareness save time,

money, ecosystems, and lives. That’s why monitoring tools range from satellites to aircraft to ground systemsand why “more data, sooner” is a powerful

goal.

The Vulcan IoT concept: low-cost sensor networks for environmental signals

Vulcan IoT won People’s Choice by focusing on an idea that feels immediately practical: deploy a network of low-cost sensors to watch variables tied to

wildfire risk and share that data in a way people can act on. The project’s pitch emphasized environmental inputs like air temperature and soil moisture,

using those signals to help forecast or flag risky conditions.

The appeal is obvious. A distributed sensor network can fill the gaps between big-picture tools (like satellites) and on-the-ground observationespecially

in remote areas. And because it’s a network, it’s not just one sensor that must be perfect; it’s many sensors building a pattern.

What makes this hard (and therefore worth applauding)

IoT systems live and die by the unglamorous details: power, connectivity, ruggedization, maintenance, and false alarms. You need to keep sensors running

for long periods, keep data flowing when networks are unreliable, and distinguish meaningful changes from noise (because “it’s hot in July” is not the

same as “a fire is starting”).

People’s Choice awards often go to projects that communicate well to non-experts. Vulcan IoT hit that sweet spot: a socially relevant problem, a plausible

approach, and a story that makes sense to anyone who has seen wildfire smoke on the horizon and thought, “This can’t be the earliest moment we notice.”

The bigger takeaway: movement gets attention, but embedded systems do the real work

The 2019 winners are easy to remember because they move in memorable ways: a boat that cruises, a drone that flaps, a rover that hops. But what really

made them Cornell Cup winners is the embedded-systems backbone underneath the motion:

- Sensing: collecting measurements that matter (water quality metrics, environmental signals, navigation inputs).

- Autonomy and control: keeping the system stable and purposeful in a messy environment.

- Integration: making mechanical, electrical, and software decisions that don’t fight each other.

- Storytelling with data: explaining why the prototype is not just cool, but useful.

Put differently: the “wow” factor gets someone to your booth. The system design convinces them you deserve a prize.

How to borrow inspiration from these projects (without copying them)

If you’re building your own robotics or embedded project, the 2019 Cornell Cup winners offer a blueprint that’s more about process than parts:

- Start with a user story: “Who uses this, when, and what problem disappears?”

- Prototype the riskiest piece first: sampling at depth, stable flapping flight, or repeatable hopping mechanicswhatever is most likely to break.

- Design for testing: build in logs, calibration procedures, and quick-swap components so failures teach you something.

- Plan your demo like a product: judges and visitors remember a clear narrative and a reliable demonstration.

And yes, it helps if your robot does something that looks like it belongs in a movie trailer. But even the best trailer needs a plot.

Real-world experiences from building Cornell Cup-style robots (extra)

You don’t have to be on a Cornell Cup team to recognize the “lived reality” of projects like these. Across student competitions, the same experiences

show up again and againand they’re especially relevant when your robot must move through water, air, or broken terrain.

First: integration always takes longer than the individual parts. A sensor might work perfectly on a bench, a motor might spin beautifully

on its own, and your code might pass every test in simulation. Then you bolt everything together and discover that the pump’s electrical noise is

confusing your readings, the vibration loosens a connector, or the vehicle’s center of gravity turned your “stable platform” into a drama student that

faints at the slightest inconvenience. The practical lesson is boring but powerful: design your wiring, mounts, and enclosures as if they matterbecause

they do.

Second: field testing is a different sport than lab testing. For an autonomous boat, real water adds wind, current, waves, floating debris,

and the occasional curious duck who did not consent to being part of your experiment. For an aerial vehicle, airflow and turbulence expose control issues

that a calm indoor space politely hides. For a hopping rover concept, every landing is a reminder that impacts don’t care about your PowerPoint.

Teams that do well tend to treat early tests as data collection, not as a pass/fail judgment on the whole project.

Third: calibration and repeatability are the “adult supervision” of engineering. Measuring dissolved oxygen and temperature sounds straightforward

until you realize the value of a measurement is only as good as the procedure behind it. What’s your calibration plan? How do you confirm your readings

haven’t drifted? How do you avoid contaminating a sample? These questions turn a cool prototype into something credible. The most successful teams build

routines: calibrate before runs, validate after runs, and log everything so you can explain surprises instead of arguing with them.

Fourth: demos reward reliability, not perfection. Competitions are full of “best version” prototypes that are brilliantright up until the moment

they don’t boot. A dependable demonstration often beats a fragile masterpiece. That’s why you’ll see experienced teams simplify, add redundancy, and create

“safe modes.” If your drone can’t flap perfectly for five minutes, can it flap steadily for thirty seconds and prove the concept? If your boat can’t run the

full autonomous route every time, can it complete a shorter path while still collecting valid data? Reliability is not a compromise; it’s a strategy.

Fifth: communication is part of the build. Events like the Cornell Cup require teams to explain tradeoffs under time pressure, to judges with different

backgrounds, while also impressing visitors who just want to see the robot do the thing. Teams learn to translate: “We chose this design because it reduces

cost” becomes “This could be deployed more often.” “We used a jumping mechanism” becomes “We can cross obstacles wheels can’t.” The best teams don’t hide

limitations; they frame them as engineering realities with a plan for iteration.

If there’s one universal experience behind projects like S.S. MAPR, TerraNova, and FWMAV, it’s this: the breakthrough moment rarely looks like a eureka

scene. It looks like a checklist, a tool kit, a pile of zip ties, and a team that learned to keep going when the prototype decided to develop a personality.

Conclusion

The 2019 Cornell Cup winners weren’t just clever gadgetsthey were strong examples of applied engineering with real stakes. S.S. MAPR showed how autonomy

and sensing can make water monitoring more scalable. TerraNova made a case for novel mobility in extreme environments like lunar caves. FWMAV proved that

bio-inspired flight can be built into a demo-ready system. And Vulcan IoT reminded everyone that embedded networks can tackle urgent, human problems like

wildfire risk.

Together, they captured what makes engineering exciting: not the parts on their own, but the way those parts become a system that can survive reality.

Or at least survive long enough to win a trophy in front of a rocket.