Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “key” means in plain English

- Before you start: collect clues in 60 seconds

- Way 1: Read the key signature (the “written music” method)

- Way 2: Analyze the chords (the “home chord” method)

- Way 3: Use the melody and your ear (the “tonal center” method)

- When it’s not that simple (and you’re not doing anything wrong)

- Fast troubleshooting checklist

- Conclusion

- Musician Experiences

- SEO Tags

Every song lives somewhere. Not emotionally (though yes, also that), but musicallyinside a key.

If you can figure out what key a song is in, you can play along faster, write better harmonies, transpose for a singer,

and stop guessing random chords like you’re throwing darts in the dark.

This guide breaks it down into three reliable, musician-tested approaches:

(1) read the key signature, (2) analyze the chords, and (3) listen for the tonal “home base”.

Use one method when you’re in a hurry, or combine them when the song is being sneaky.

What “key” means in plain English

A key is basically a song’s home: the note (the tonic) the music wants to land on, plus the

most common set of notes used around it (the scale). Most modern songs are in a major key

(brighter, “happy-ish”) or a minor key (darker, moodieraka “indie film soundtrack at 2 a.m.”).

Important detail: the same collection of notes can belong to a relative major/minor pair

(for example, C major and A minor share the same key signature). That’s why the best key-finding strategies look for

the “home” feeling, not just a list of notes.

Before you start: collect clues in 60 seconds

- If you have sheet music: check the key signature (sharps/flats at the beginning).

- If you have chords: write down the chords used in the verse/chorus (even a short loop helps).

- If you only have audio: listen for the note/chord that sounds like “done” or “home.”

- Bonus clue: pay attention to the bassbass notes often outline the tonal center clearly.

Way 1: Read the key signature (the “written music” method)

If you’ve got sheet music (or a lead sheet that includes a key signature), congratulationsyou have a cheat code.

The key signature narrows your options immediately, usually to a major key and its relative minor.

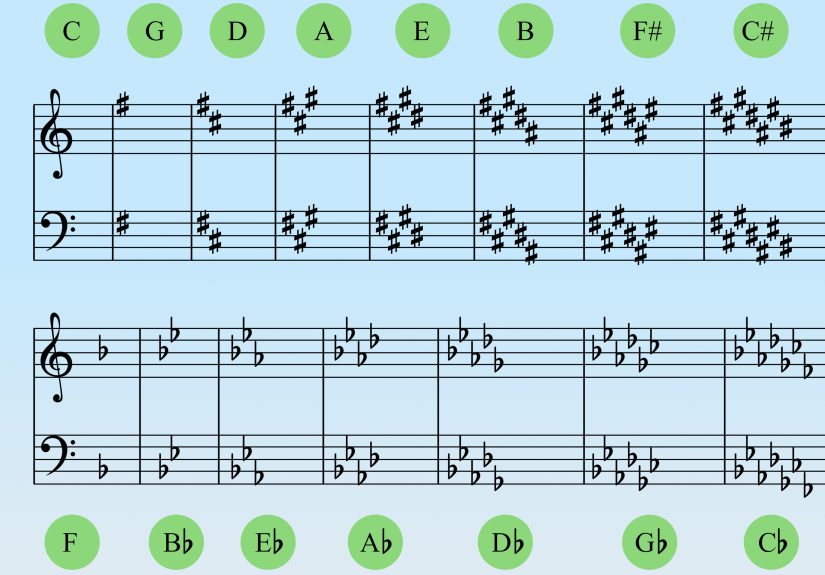

Step 1: Count the sharps or flats

Look right after the clef at the start of each staff. If you see sharps (♯) or flats (♭), count them.

No sharps/flats? That’s the easiest one: it’s either C major or A minor.

Step 2: Convert the key signature to a major key quickly

Use these two fast rules:

- Sharps: find the last sharp in the key signature, then go up one half step. That note is the major key.

- Flats: the second-to-last flat is the major key (except for one flatsee below).

Special case: one flat means F major (and its relative minor, D minor).

Two flats? The second-to-last flat is B♭, so the major key is B♭ major. You get the idea.

Step 3: Decide: major key or relative minor?

Key signature alone doesn’t tell you whether the song is in the major key or its relative minor.

To choose correctly, look for one (or more) of these:

- Ending tone/chord: does the music feel resolved on the major tonic or the relative minor tonic?

- Melody emphasis: which note sounds like “home” in the melody (held longer, repeated, placed at phrase endings)?

- Chords: does the harmony strongly point to a major I chord or a minor i chord?

Example: no sharps or flats

If your key signature has no sharps or flats, your “note set” matches both C major and A minor.

If the chords keep landing on C (or the song ends on C), you’re probably in C major. If it gravitates toward Am (or uses E or E7 as a strong pull back to Am),

you’re probably in A minor.

Helpful tool (still human-powered): the circle of fifths

The circle of fifths is a simple map of key signatures. If you memorize even a few landmarks (0 sharps/flats = C major/A minor; 1 sharp = G major/E minor; 1 flat = F major/D minor),

you’ll speed up your key ID dramatically.

Way 2: Analyze the chords (the “home chord” method)

If you don’t have a key signature (common in guitar tabs, chord charts, and “here are the chords, good luck” internet posts),

your best friend is harmonic function: how chords create tension and release.

Step 1: Write down the chords and look for the “big three”

In most major keys, the most common functional chords are:

I (tonic, home), IV (predominant/subdominant, “going somewhere”), and V (dominant, “we must return home now”).

If you can identify a likely I, IV, and V, you can usually identify the key.

Quick pattern: if you see three chords that could be I–IV–V in some key, that key is often your answer.

Example: A, D, and E show up together constantlythose are I, IV, and V in A major.

Step 2: Hunt for cadences (the musical equivalent of a period)

A cadence is a harmonic landing point. In tonal music, cadences are a huge clue because they often spell out the key.

Listen for these classic “resolution moves”:

- V → I (authentic cadence): the strongest “we’re home” sound in major keys.

- IV → I (plagal cadence): the “Amen” vibestill home, but softer.

- V → vi (deceptive cadence): feels like it dodges home at the last second (still useful data!).

Step 3: Use the bass line like a detective uses fingerprints

Bass notes often outline roots clearly. If you’re stuck between two possible keys, pay attention to which note the bass returns to

at phrase endings or section transitions. The bass “doesn’t always tell the truth,” but it lies less often than the rest of the band.

Worked example: G – D – Em – C

This progression is everywhere in pop/rock. It contains chords that fit neatly in G major:

G (I), D (V), Em (vi), C (IV).

If the song tends to resolve from D back to G, or starts/ends sections on G, you’re very likely in G major.

But notice: the same chord set also relates closely to E minor (the relative minor of G major).

To decide, ask: does Em feel like the true “home” chord? Do phrases land on Em with a sense of completion?

If yes, you might be in E minor with a very major-friendly chord palette.

Minor-key clue: look for the “raised 7th” behavior

Many minor-key songs use a dominant chord that strongly pushes back to the minor tonic.

That push often comes from the leading tone (scale degree 7) resolving up to the tonic.

In practice, you might hear a V chord in minor that sounds especially “urgent” (often a major V chord in an otherwise minor context).

That kind of tension-and-release is a loud hint that you’re in minor.

Way 3: Use the melody and your ear (the “tonal center” method)

This is the method you use when you don’t have sheet music, don’t have a chord chart, and the internet has only supplied

a blurry video titled “SONG??? help pls.” You can still find the keybecause your ear can detect tonal gravity.

Step 1: Find the note that feels like “home”

Play the song and pause at the end of a phrase. Hum a note that feels stablelike the music could stop there without sounding unfinished.

Then find that note on your instrument. That note is a strong candidate for the tonic.

Pro tip: don’t choose the flashiest note. Choose the note that feels like it owns the couch and pays rent.

Step 2: Listen for “pull” notes (especially 7 → 1 and 2 → 1)

In many melodies, the sense of key is reinforced by tendency tones:

- 7 → 1: the leading tone resolving to tonic has a strong “magnet” feeling.

- 2 → 1: a step down into the tonic often closes melodic phrases cleanly.

If you repeatedly hear a melody leaning into the same “arrival” note at the ends of lines, that arrival note is probably the tonic.

Step 3: Check the melody notes against a likely scale

Once you suspect a tonic, collect a handful of melody notes (even 5–8 notes is enough). Ask:

do these notes fit better in a major scale, a natural minor scale, or something else (like a mode)?

Example: if your tonic candidate is A and the melody frequently uses C natural and G natural, you might be hearing A minor (A–B–C–D–E–F–G).

If it uses C♯ and G♯ instead, you’re more likely in A major. If it uses C♯ but G natural, you may be in a modal situation (hello, Mixolydian neighbors).

Ear-training drills that actually help (and won’t ruin your afternoon)

- Cadence loop: play V–I in a few keys and sing the tonic note after it resolves.

- Scale-degree labeling: hear a short progression, then identify whether a melody note feels like 1, 3, 5, etc.

- One-song-per-week challenge: pick a simple tune and find the tonal center by humming first, then confirming on an instrument.

Optional tech help: key-detection tools (use with skepticism)

Tuner apps, DAWs, and key-detection plugins can suggest a key quicklyespecially for simple, diatonic material.

But they can struggle with:

- songs that modulate (change key),

- songs that borrow chords outside the key,

- blues-based music, and

- modal music where “major/minor” labels don’t tell the whole story.

Use the software as a second opinion, not as a judge, jury, and executioner of your music theory grade.

When it’s not that simple (and you’re not doing anything wrong)

1) Relative major vs. relative minor ambiguity

If the chords and notes fit two keys (like C major vs. A minor), the deciding factor is usually the tonal center:

what feels resolved at section endings, what gets emphasized melodically, and what chord feels like “home base.”

2) Modes (the “same notes, different home” situation)

Sometimes a song uses the notes of a major scale but treats a different note as the centerthis is modal writing.

Example conceptually: music can use the notes of C major while centering on D (D Dorian).

If your “key signature method” says one thing but your ear says another, modes might be the reason.

3) Borrowed chords and “spicy” harmony

Pop and film music often borrow chords from parallel keys (like borrowing from the minor while in major).

One or two outside chords doesn’t necessarily mean the key changed. It might just mean the songwriter likes drama.

4) Key changes and modulations

Some songs genuinely change keys between sections (verse in one key, chorus in another, bridge goes sightseeing).

In that case, your job isn’t to find the keyit’s to find the key for each section.

5) Loop-based music with no clear ending

If a song loops four bars forever (common in electronic and hip-hop), “the last chord” may not exist.

Focus on where the loop feels like it resets, what the bass treats as home, and which chord sounds most stable.

Fast troubleshooting checklist

- If you have sheet music: start with the key signature, then confirm with the ending chord.

- If you have chords: look for I/IV/V relationships and cadence behavior (tension → release).

- If you only have audio: hum the “home” note, find it on your instrument, then test major vs. minor.

- If two keys seem possible: decide by tonal center (what feels finished?).

- If nothing feels finished: consider modes, borrowed chords, or modulation.

Conclusion

Finding a song’s key isn’t magicit’s pattern recognition.

Start with the clearest clue available: key signature (if you have it), chords (if you can list them), or your ear (if you’re working from audio).

The more you practice, the faster your brain will spot “home.”

And when you get it wrong? Congratulationsyou just did ear training. That’s how it works.

Music theory is less about being perfect and more about getting better at asking the right questions.

Musician Experiences

Here are some real-world, totally normal experiences musicians run into while learning to identify keysbecause the skill usually develops

in the messy middle of rehearsals, open mics, and “wait, what chord is that?” moments.

Experience 1: The cover-band scramble

A guitarist gets called up to sit in on a song they “kind of know.” There’s no chart, the singer counts it off, and the band launches.

The guitarist’s survival move is to watch the bassist’s left hand (or listen to the lowest notes) and hunt for a chord that feels like “home.”

Often, that home chord shows up at the end of the chorus or right before the next versewhere the music resets emotionally and harmonically.

Once the guitarist finds that center, the next step is quick: test whether the vibe is major or minor by trying a major third versus a minor third

over that home note. If the major third sounds like sunshine and the minor third sounds like a plot twist, the key is basically solved.

Experience 2: The “tabs lied to me” lesson

A beginner learns a song from tabs and later tries to play along with the recordingonly to discover everything sounds slightly off.

That moment often introduces two key concepts at once: transposition (the band recorded in a different key, or the tab is wrong)

and relative keys (the chords might “fit” but not feel resolved).

A helpful fix is to stop trusting the printed chord names for a second and instead identify the tonal center by ear:

hum the note that feels finished, find it on the instrument, then rebuild the likely diatonic chord family around it.

Suddenly the song becomes playable, and the musician learns a powerful truth: the key is in the sound, not the screenshot.

Experience 3: The piano-player’s shortcut (and why it works)

Pianists often learn key-finding quickly because the keyboard makes patterns visible. When noodling along to a track,

they’ll test a handful of notes until they find a set that doesn’t clash. Then they’ll play a basic I–IV–V–I in a suspected key

to see whether it “locks in” with the song’s harmony. If it locks in, greatnow they can build chords, bass motion, and fills.

If it mostly locks in but a couple notes feel “wrong,” that usually points to borrowed chords, blues language, or a modal center.

In other words: even the “wrong” notes become useful clues.

Experience 4: The ear-training glow-up

Many musicians describe a tipping point where key detection stops feeling like math and starts feeling like gravity.

Early on, everything is slow: pause the song, guess the tonic, test a scale, change your mind, test again.

With repetition, the brain starts recognizing the sound of cadencesespecially the dominant-to-tonic pullalmost instantly.

That’s why practicing cadences and tonal centers helps so much: it teaches the ear what “home” sounds like across different keys.

Over time, musicians don’t just identify keys faster; they also improvise more musically, because they feel where phrases want to land.

It’s less “What key is this?” and more “Oh, we’re going therecool.”

The common thread across these experiences is that key identification improves fastest when it’s attached to a practical goal:

joining a jam, transposing for a vocalist, improvising a solo, or writing harmony that actually supports the melody.

The theory is the mapbut the experience of listening, testing, and confirming is how the map becomes second nature.