Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Quick snapshot: the main COVID vaccine types (and what you’ll see in the U.S.)

- How COVID vaccines work (no lab coat required)

- mRNA COVID vaccines (Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech)

- Protein subunit COVID vaccine (Novavax)

- Where the U.S. vaccine landscape is right now

- How to think about “which vaccine type should I get?”

- Conclusion

COVID vaccines aren’t one-size-fits-all. They’re more like different teaching styles for the same lesson:

“Hey, immune systemif you see that virus again, don’t be polite. Be prepared.”

Some vaccines hand your cells a short-lived set of instructions (mRNA). Others show your immune system a

ready-made “most-wanted poster” (protein subunit). Either way, the goal is the same: build immune memory

so your body can respond faster and stronger the next time SARS-CoV-2 shows up uninvited.

This guide breaks down the major types of COVID vaccines, how each works, what “effectiveness”

really means in 2025–2026 (spoiler: preventing severe illness matters most), and the most common

COVID vaccine side effectsplus the rare ones you should actually know by name.

Quick snapshot: the main COVID vaccine types (and what you’ll see in the U.S.)

| Vaccine type | How it “teaches” immunity | Examples (U.S.) | Big-picture notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA | Gives your cells temporary instructions to make a harmless piece of spike protein. | Moderna (Spikevax / mNexspike), Pfizer-BioNTech (Comirnaty) | Quick to update for new variants; strong protection against severe outcomes. |

| Protein subunit | Delivers pre-made spike protein plus an adjuvant to boost the immune response. | Novavax (Nuvaxovid) | More “traditional” platform; still targets spike; also updated over time. |

| Viral vector | Uses a harmless virus as a delivery vehicle for spike instructions. | (Not currently available in the U.S. for COVID) | Historically important; rare clotting syndrome was a key safety topic for some products. |

| Inactivated / whole-virus | Uses a killed version of the virus to train immune recognition. | Common globally; not a main U.S. option | Long-used approach in vaccinology; availability varies by country. |

| Live attenuated / intranasal | Uses a weakened form (or nasal approach) designed to mimic infection more closely. | Not a standard U.S. COVID option | In theory, could help mucosal immunity; depends on product approvals. |

How COVID vaccines work (no lab coat required)

They train your immune system to recognize “spike”

Most COVID vaccines focus on the virus’s spike protein because it’s the part the virus uses to latch onto

and enter human cells. Vaccination teaches your immune system to recognize spike so it can respond quickly

if you’re exposed later. That response includes:

- Antibodies that can block infection by binding to the virus.

- T cells that help coordinate the response and destroy infected cells.

- Immune memory that speeds up the whole process the next time around.

Why “breakthrough infections” can still happen

If you’ve ever thought, “Wait, I got vaccinated and still caught COVIDwhat gives?” you’re not alone.

Two big realities explain it:

-

Variants change the target. The virus keeps evolving. Updated vaccines aim to match

what’s circulating, but the match is never perfect forever. -

Protection against infection tends to wane faster than protection against severe illness.

Antibody levels decline over time (normal biology, not a betrayal), while memory responses still help

reduce the risk of hospitalization and death.

In other words: vaccines are not a magical force field. They’re more like a really good alarm system and

response team. Sometimes a burglar gets in; the goal is making sure the situation doesn’t turn into a disaster.

mRNA COVID vaccines (Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech)

How mRNA vaccines work

An mRNA COVID vaccine delivers a tiny piece of genetic code (messenger RNA) that tells your cells

how to make a harmless fragment of the spike protein. Your immune system sees that spike fragment, practices

responding to it, and builds memory.

Key detail that clears up a lot of internet chaos: mRNA is temporary. Your body breaks it down after it delivers

its message. It does not change your DNA. Think of it as a disposable recipe card, not a permanent edit to

the family cookbook.

Effectiveness: what the numbers really mean (then vs. now)

Early clinical trials for the original mRNA vaccines showed very high efficacy against symptomatic COVID in a world

where most people had no prior immunity and the virus hadn’t yet rolled out a dozen plot twists. Those results were

a big reason mRNA became the headline act.

In 2024–2025 and into 2025–2026, “effectiveness” is more nuanced because most people have some combination of

vaccine- and infection-derived immunity, and variants are different. Real-world studies commonly focus on outcomes like

emergency visits, hospitalization, and deathbecause those are the stakes that actually keep doctors up at night.

-

Against severe outcomes: Updated vaccines continue to provide additional protection against hospitalization,

especially in older adults and people at higher risk. -

Against getting infected at all: Protection is usually lower than it was in 2021 and it wanes with timeespecially

as the virus evolves.

Practical takeaway: when you hear “33% effectiveness,” that doesn’t mean “the vaccine failed 67% of the time.”

It means, in that study and time window, the vaccinated group had about one-third fewer of the measured outcome

than a comparable unvaccinated group. Different outcomes (infection vs. hospitalization), different time windows,

and different populations can produce very different numbers.

Side effects: common, expected, and rare-but-important

Most COVID vaccine side effects are short-lived signs your immune system noticed the assignment.

Common ones include:

- Sore arm, redness, or swelling at the injection site

- Fatigue, headache, muscle aches

- Fever or chills (often more noticeable after a dose that “refreshes” immunity)

Rare side effects get more attention (because they’re rare and scary-sounding), but they’re worth understanding accurately:

-

Myocarditis/pericarditis: Rarely observed after mRNA vaccination, with the highest observed risk in males

in the teen/young adult range. Many reported cases have improved with treatment and rest. -

Severe allergic reactions (anaphylaxis): Uncommon, typically happens soon after vaccinationthis is why

clinics monitor people briefly after the shot. - Syncope (fainting): Can occur with injections in general (the body’s dramatic way of saying, “Needles are a lot.”).

If you ever have chest pain, shortness of breath, or a racing/pounding heartbeat after vaccinationespecially within the first week

seek medical care. Most people will never experience this, but it’s a “don’t ignore it” category.

Protein subunit COVID vaccine (Novavax)

How protein subunit vaccines work

A protein subunit COVID vaccine skips the instruction step and brings the immune system a pre-made piece of

the spike protein. It also includes an adjuvantan ingredient that boosts the immune response so your body

treats the lesson as worth remembering.

If mRNA is a recipe card, a protein subunit vaccine is the sample tray at the grocery store:

“Try this. Recognize it. Next time you see it, act accordingly.”

Effectiveness: what we know

Novavax demonstrated strong efficacy in its major clinical trials during earlier waves of the pandemic, and its updated versions are

designed to better match circulating variants over time. Like mRNA vaccines, the most consistent value across variants is usually in

reducing the risk of severe outcomesespecially for people at increased risk.

Side effects and safety notes

Common side effects overlap with other vaccines: arm soreness, fatigue, headache, muscle aches, and sometimes fever/chills.

Novavax also includes warnings about rare myocarditis/pericarditis reports and the possibility of allergic reactionsso the same

“pay attention to chest symptoms and seek care if they occur” guidance applies here too.

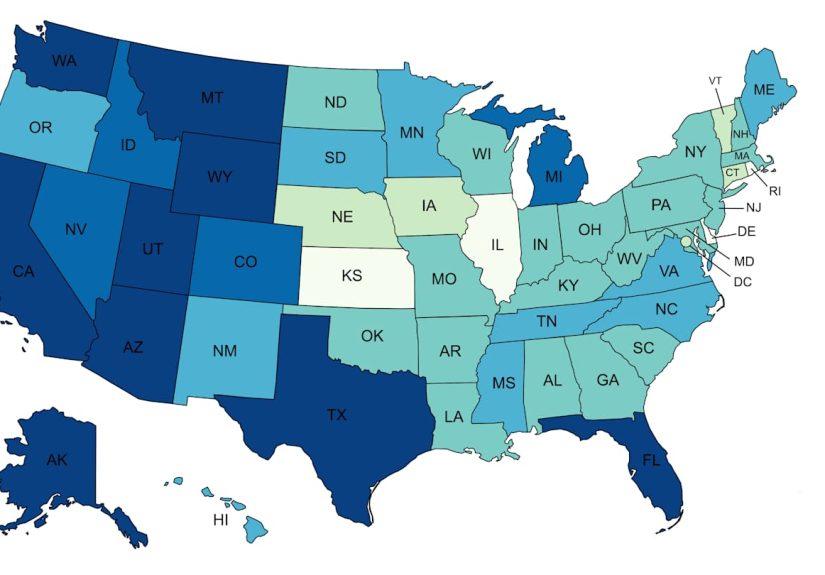

Where the U.S. vaccine landscape is right now

In the United States, current guidance centers on mRNA vaccines (Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech) and a

protein subunit vaccine (Novavax). Recommendations are framed around

individual-based decision-making, with the risk-benefit balance most favorable for people at increased risk of severe disease.

Vaccine formulations are updated to better match what’s circulating. For the 2025–2026 season, U.S. formulations are based on the

Omicron JN.1 lineage (with specific strain selections depending on product). That update process is one reason you may hear COVID

vaccines discussed more like “seasonal respiratory protection” nowsimilar in spirit (not identical) to how we think about flu shots.

How to think about “which vaccine type should I get?”

Your best choice is usually the one that’s recommended for your age/risk group and actually available to you.

Still, people commonly weigh factors like:

- Age eligibility and whether a product is approved/available for your age group.

- Medical history (e.g., prior severe allergic reaction to a component).

- Previous side effects and personal risk tolerance (especially for rare events).

- Timing: upcoming travel, caregiving responsibilities, big work deadlines (nobody wants “booster fatigue” on presentation day).

If you’re immunocompromised, pregnant, or have a history of myocarditis/pericarditis, a clinician can help you interpret the latest guidance

and make a plan that fits your specific situation. That’s not a cop-outit’s what “shared decision-making” is supposed to look like.

Conclusion

The big idea is simple: different types of COVID vaccines use different delivery methods, but they aim to teach your immune system

the same lessonrecognize spike fast, respond hard, and reduce your chances of severe outcomes. In today’s variant-rich reality,

“effectiveness” is less about never getting infected and more about keeping you out of the hospital (and off the worst parts of the internet at 2 a.m.).

If you remember nothing else, remember this: vaccines are a risk-and-benefit calculation, and the calculation shifts based on age, immune status,

and what’s circulating. That’s why updated formulations, boosters, and individualized recommendations exist.

Real-world experiences: what people commonly report (the human side of the science)

Beyond the charts and acronyms, vaccination is a lived experienceusually a very ordinary one. Most people describe the appointment itself as quick:

a check-in, a few screening questions, a small pinch, and then the classic “sit here for a bit” observation period. If you’re needle-neutral, it’s a

minor errand. If you’re needle-avoidant, it can feel like a boss battlebut a short one, and the kind where a deep breath and a distraction tactic

(music, scrolling, intense focus on the ceiling tile pattern) actually helps.

The most common “experience” is simply a sore arm that shows up a few hours later. People often compare it to a mild workout achelike your deltoid

did one push-up too many and is now filing a complaint. Fatigue and headache are also frequent characters in the post-shot story. Some people feel

totally normal; others feel like their body requested an early bedtime. Neither reaction is a scorecard for whether the vaccine “worked.”

Immune systems are quirky, and they don’t all narrate their activity the same way.

Another pattern people report is timing: symptoms, if they happen, often peak within a day or two and then fade. That’s why many people schedule

their vaccine when they have flexibilitylike a Friday afternoon, a day off, or a weekend where “plans” can be downgraded to “snacks and streaming.”

Caregivers and parents commonly plan ahead as well, lining up easy meals and lighter schedules just in case a kid (or an adult) is cranky, achy,

or unusually sleepy the next day.

People also talk about the mental side: relief, annoyance, pride, or all three in a rotating carousel. Relief because it feels proactive. Annoyance

because nobody asked for a multi-year respiratory saga. Pride because doing something small for your health can feel like reclaiming a tiny bit of

control. And yes, there’s a special category of experience reserved for the “I’m fine” crowd who still tells everyone they got the shot because their

immune system is apparently a quiet professional who doesn’t need applause.

Finally, there’s the practical reality that “getting vaccinated” is sometimes less about science and more about logistics: figuring out availability,

insurance questions, pharmacy appointments, anddepending on where you livewhether you need a clinician’s sign-off. Many people describe the process

as smoother now than in the earliest vaccine rollout, but still occasionally confusing when recommendations change or product names update. If you’ve ever

stared at “Spikevax,” “Comirnaty,” and “Nuvaxovid” and thought, “Are these vaccines or spaceship models?”congratulations, you’re having the most normal

modern-healthcare reaction imaginable.