Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Does “Four Billion If Statements” Actually Mean?

- Checking Even vs. Odd the Normal Way (aka The Sane Way)

- How Compilers React to Absurd Code

- Time–Memory Tradeoffs: When “Precomputation” Goes Off the Rails

- Why Long Chains of if Statements Are a Code Smell

- What We Learn About Compilers from This Experiment

- Practical Takeaways for Everyday Code

- Hands-On Experiences & Lessons from the “Four Billion Ifs” Mindset

- Conclusion: A Giant Joke with Serious Lessons

Somewhere on the internet, a programmer asked a simple question with a gloriously chaotic twist:

“What if, instead of using % 2 or a bitwise trick to check if a number is even…

I just wrote an if statement for every possible 32-bit integer?”

That thought experiment turned into a very real project: generating and compiling

four billion if statements to decide whether a number is odd or even.

Hackaday picked up the story, highlighting how modern compilers, linkers, and operating systems

react when you throw something this absurd at them.

It’s the kind of experiment that makes every CS instructor groan, every systems programmer

raise an eyebrow, and every performance nerd secretly smile. It’s also a surprisingly good way

to learn about compiler optimization, time–memory tradeoffs, and the limits of “doing

something stupid on purpose.”

What Does “Four Billion If Statements” Actually Mean?

A 32-bit unsigned int can represent values from 0 to

4,294,967,295. That’s a state space of about 4.29 billion distinct values. The

project, originally described by Andreas Karlsson and later featured on Hackaday, tried to cover

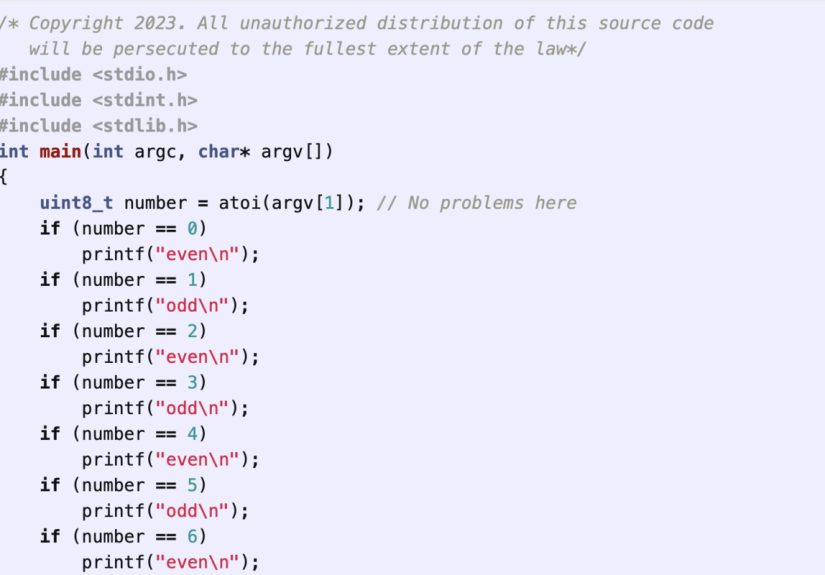

that entire range with straight-line code: essentially a giant sequence like:

Of course, no one sat down and typed this out by hand. A generator program emitted C code that

expanded into billions of comparisons, producing a source file on the order of tens of gigabytes

and a final binary around 40 GB once all those comparisons were assembled into machine code.

At that point, your compilation pipeline stops being “just another build” and starts becoming

an experiment in how far you can push:

- Compiler front ends that need to parse and analyze a mountain of code

- Optimizers that try (and often fail) to make sense of the giant chain of conditionals

- Linkers and loaders trying to wrestle a 40 GB blob into something executable

- The operating system, which has to map that monster into virtual memory and pretend

life is normal

Checking Even vs. Odd the Normal Way (aka The Sane Way)

Before we go deeper into the madness, it’s worth remembering that the original problemchecking

if a number is even or oddis trivial in normal code. You have at least two standard, fast,

battle-tested options:

1. Using the modulo operator

This is clear, readable, and supported in every programming language you’re likely to touch.

You’ll find this approach in classic tutorials, textbooks, and beginner programming guides

everywhere.

2. Using a bitwise AND

Under the hood, being even or odd is all about the least significant bit. If that bit is 0, the

number is even; if it’s 1, the number is odd. Using n & 1 is a classic low-level

trick often recommended on Q&A forums and in systems programming discussions when you want

to be explicit about what the CPU is actually doing.

Both of these approaches compile down to a handful of instructions and take effectively constant,

negligible time on modern hardware. That’s why the four-billion-ifs approach is intentionally

“wrong”: it’s not supposed to be a better solution. It’s a stress test for the tooling.

How Compilers React to Absurd Code

Modern optimizing compilers are very good at taming messy code. They routinely:

- Inline small functions

- Reorder instructions to better use the pipeline

- Turn predictable branches into efficient machine instructions

- Transform

switchand if/else chains into jump tables or decision trees

Conditional logic is a prime target for these optimizations. Compilers estimate branch

behaviors, hoist invariants, and, when possible, collapse long chains of conditions into more

efficient structures.

But four billion if statements? That’s not “challenging,” that’s “please don’t.”

You’re asking the compiler to:

- Parse and store an enormous abstract syntax tree (AST)

- Run optimization passes over a control flow graph with billions of branches

- Emit machine code for every single comparison in sequence if it can’t simplify it away

In practice, different toolchains react differently. Some compilers may:

- Run out of memory or hit internal limits

- Take an extremely long time just to get through the front-end parsing stage

- Generate an enormous, barely executable binary

Hackaday notes that getting this monstrosity to compile was a fight: modern tools do their best

to protect you from yourself, but at some scale, they just throw up their hands and walk away.

Time–Memory Tradeoffs: When “Precomputation” Goes Off the Rails

On paper, you can think of four billion if statements as an extreme sort of

precomputation. Instead of doing work at runtime, you:

- Generate all the logic ahead of time.

- Compile it into a huge binary.

- Ship that binary and let it “just” run comparisons.

Andreas Karlsson’s original write-up describes this explicitly as a

time–memory tradeoff: spend enormous disk and memory resources so that checking

even/odd conceptually becomes “just” following a path in a huge block of compiled instructions.

The end result? A file on the order of 40 GB, mapped into virtual memory so the host program can

treat it as if it’s all there and let the operating system decide which parts actually live in

RAM at any moment. It’s a clever abuse of memory mapping, but it’s also hilariously impractical

for any real-world problem.

Several blog posts and discussion threads that reacted to this experiment point out the obvious:

if you’re going to precompute, at least use a data structure tuned for lookuplike a table in

memory, a compressed bitmap, or some compact encodingrather than a giant wall of branching

instructions.

Why Long Chains of if Statements Are a Code Smell

Most developers will never write billions of conditions, but many of us have seen (or written)

functions that are suspiciously long sequences of if / else if

/ else. That’s not just an aesthetic problem; it’s usually a sign there’s a better

abstraction lurking nearby.

Software engineering discussions consistently recommend avoiding both giant switch

blocks and massive if/else ladders when you can replace them with data-driven designs or

dispatch tables.

Some healthier patterns include:

- Lookup tables: Map from keys to function pointers, lambdas, handlers, or

configuration structs. - State machines: Represent behavior as explicit states and transitions

instead of ad-hoc branching everywhere. - Polymorphism / strategy objects: Let each implementation handle its own

behavior and remove the central “god” function. - Pattern matching (in languages that support it): Express conditions in a

more structured, declarative way.

So while the four-billion-if experiment is intentionally extreme, it’s really just a giant,

neon-lit version of a common design smell.

What We Learn About Compilers from This Experiment

As silly as it seems, compiling four billion if statements teaches a few serious lessons about

how compilers and modern hardware work:

1. Compilers are powerful, not magical

Optimizers are great at cleaning up messy but reasonable code. They’re not designed for

pathological inputs that blow up their internal data structures. At a certain size, even linear

passes over your code become prohibitively expensive.

2. Control flow matters for performance

Long chains of unpredictable branches are the enemy of modern CPUs, which thrive on predictable

branch patterns and tight loops. Billions of sequential comparisons with highly varied outcomes

murder branch predictors and instruction caches.

3. Time–memory tradeoffs have limits

Precomputation is a powerful technique, but it has to respect reality: storage costs, I/O time,

and memory bandwidth. A lookup that requires paging in chunks of a 40 GB binary will always

struggle to compete with a two-cycle bitwise operation.

4. “Because we can” is a valid learning strategy

Nobody is going to ship four-billion-if production code (or at least we all deeply hope not).

But as a teaching tool, it’s fantastic. It forces you to confront:

- Where your toolchain breaks down

- Which assumptions you make about “infinite” resources

- Whether your mental model of compilers matches reality

Practical Takeaways for Everyday Code

You probably won’t generate billions of conditionals, but you will face design

decisions where your code is slowly drifting toward “branch spaghetti.” Some practical rules of

thumb:

- If your function is more

ifthan logic, it’s time to refactor. - If you’re encoding data in code (like a giant list of special cases), consider a table or

configuration file instead. - If you’re nesting conditions more than three or four levels deep, a clearer abstraction

probably exists. - If performance matters, think about branch predictability and cache behavior, not just the

number of lines of code.

The moral of the Hackaday story isn’t “don’t ever write if statements.”

It’s respect algorithms, respect data structures, and don’t try to brute-force your way

past basic math.

Hands-On Experiences & Lessons from the “Four Billion Ifs” Mindset

You don’t need a 40 GB binary to feel the pain of bad branching. Most of us meet a smaller,

more relatable version of this problem early in our careers.

Maybe it’s a “menu handler” function in a desktop app. It starts out clean:

Then new features land. Every sprint adds a couple more options. Months later you’re staring at

a 300-line function with a hundred branches, each one subtly different. Every bug report sounds

like: “When I do X after Y but before Z in dark mode, the app crashes.” Congratulations, you’ve

built the small-business version of four billion if statements.

The debugging experience is always the same: you drop breakpoints, step through a forest of

branches, and keep asking yourself, “Why is this logic even here?” It’s not that any single

if is wrong; it’s that the entire structure no longer fits in your head.

On the performance side, I’ve seen embedded teams obsess over shaving cycles off a loop, only to

discover that the real bottleneck was a giant decision tree running on every packet. The code

had grown organically: “Just add another if for that edge case.” Years later,

nobody dared touch it, and everyone was afraid to delete a branch because “that might be for a

legacy customer.”

The turning point usually comes when someone finally says, “What if we treated this as data?”

Instead of a giant if/else ladder, the logic gets rewritten as a table:

Now adding a feature is as simple as inserting a row. Testing gets easier tooyour “four billion

ifs” collapse into a data-driven pattern. The underlying lesson is the same one the Hackaday

story dramatizes: if you’re encoding a decision space, there’s almost always a smarter way than

writing every case as raw control flow.

Another common experience is seeing someone avoid “expensive” operations like modulo based on

outdated folklore. They’ll bend over backwards to avoid % 2, inventing elaborate

(“clever”) alternatives that are harder to reason about and often no faster in practice. Modern

compilers are very good at turning simple, clear expressions into efficient machine code, and

CPUs are optimized around common patterns like division by constants.

That’s where experiments like compiling four billion if statements are oddly healthy. They

shake you out of micro-optimizing individual instructions and force you to zoom out:

- What is the simplest correct algorithm?

- Can the compiler already optimize this pattern well?

- Am I trading clarity for imaginary speed?

- Is my “optimization” actually making the system harder to maintain?

Once you’ve seen what it takes to brute-force a trivial problem into a 40 GB executable, it gets

a lot easier to justify the boring, mathematically sound solution. You learn to trust simple

primitiveslike % 2 or n & 1and to save your creativity for the

higher-level design where it really matters.

In the end, the four-billion-if saga is a love letter to both curiosity and restraint. It shows

how far you can push your tools for funand why, in production code, you almost never should.

Conclusion: A Giant Joke with Serious Lessons

Compiling four billion if statements is a beautiful, ridiculous demonstration of just how

over-the-top you can get when you ignore basic computer science principles. It abuses

compilers, terrifies RAM, and dramatically loses to a single line of code using modulo or a

bitwise check.

But that’s exactly why the story is so compelling. It turns a tiny problemchecking if a number

is eveninto a microscope slide that reveals how compilers, linkers, operating systems, and

hardware behave at the extremes. You walk away with more respect for algorithms, more sympathy

for your toolchain, and a healthy suspicion of any design that feels like “a billion special

cases.”

The next time you’re tempted to bolt just one more if onto an already huge branch

ladder, remember: somewhere out there is a 40 GB binary that exists so you don’t have to go

down that path yourself.