Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- The Home-Computer Cage Match of 1983

- Meet the Coleco Adam: The All-In-One That Actually Meant It

- Specs That Looked Legit (Especially in a Toy-Store Aisle)

- Why the Adam Looked Like a Commodore 64 Rival

- Why the Commodore 64 Still Won the Living Room

- The “Almost” Part: Problems That Sank a Great Pitch

- January 1985: Coleco Pulls the Plug

- What Would Have Made the Adam a True Commodore 64 Challenger?

- Why People Still Love the Coleco Adam

- Modern-Day Experiences: Using a Coleco Adam Today (No Time Machine Required)

- Conclusion

In the early 1980s, home computers weren’t just “devices.” They were declarations. They were kitchen-table

arguments. They were the reason your family suddenly cared about things like “RAM” and “disk drives”

even though your dad still called the VCR “the machine.”

And right in the middle of that glorious chaos, Colecoyes, the toy company behind the

ColecoVisiondecided it could totally take on the Commodore 64. Not by nibbling around the edges,

but by swinging a full-sized, printer-in-the-box, “family computer system” haymaker.

That machine was the Coleco Adam: ambitious, surprisingly capable, and tragically famous for proving

that “cool on paper” and “works in your living room” are two different species of animal.

The Home-Computer Cage Match of 1983

To understand why the Adam mattered, you have to remember what the market felt like in 1983: crowded,

loud, and allergic to patience. New machines popped up constantly, prices dropped fast, and shoppers

wanted instant results. A computer had to be affordable, useful, and funpreferably before your kid lost

interest and went back to arcade tokens.

The Commodore 64 was the heavyweight champ

The Commodore 64 hit a sweet spot: 64 KB of RAM, strong graphics and sound for games, and an ecosystem

that ballooned into thousands of titles. Better yet, Commodore didn’t just competeit started

price wars. That matters because in the home-computer world, features are nice… but an irresistible price is

basically a cheat code.

Coleco saw an opening: “Bundle everything”

Coleco’s big idea wasn’t to out-nerd Commodore on chips and specs. It was to sell a whole solution.

Not “buy a computer, then maybe buy storage, then maybe buy a printer.” Coleco wanted you to buy one box,

take it home, and immediately do something usefullike writing a book reportthen reward yourself with a

video game.

Meet the Coleco Adam: The All-In-One That Actually Meant It

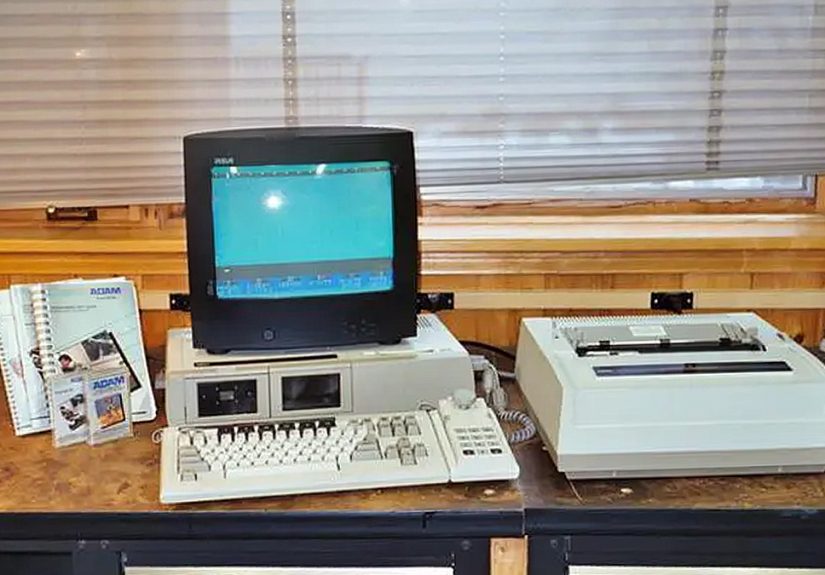

The Coleco Adam launched as a “family computer system” with a very specific pitch: value through bundling.

Depending on the package, you could buy it as a standalone computer or as an expansion that turned your

ColecoVision console into a computer. That was clever: Coleco already had gamers in the house and wanted

to convert them into “home computer families” without asking them to abandon the console they loved.

What you got in the box (and why it wowed people)

Contemporary coverage made the point plainly: the Adam arrived with a lot of hardware and software bundled

togetherkeyboard, printer, storage, controllers, and programsat a price that made competitors scramble

to announce bundles of their own. If you were new to computers, it felt like skipping the confusing “pick

your peripherals” phase and jumping straight to the part where you actually use the thing.

SmartWriter: the “instant app” before instant apps were cool

The Adam’s secret weapon was SmartWriter, a word processor built into ROM. Turn on the system, hit the right

key, and boom: you’re typing. No waiting for a program to load. No “Insert Disk 1 of 17.” No ritual dance

around a cassette deck while whispering, “Please don’t error at 99%.”

This mattered because it positioned the Adam as both a game-capable machine and a productivity toolan

8-bit computer that wanted to be taken seriously in the same conversation as the Apple II family, but at

a mass-market price.

Specs That Looked Legit (Especially in a Toy-Store Aisle)

The Adam was built around a Zilog Z80A-class CPU (a familiar workhorse in the era) and paired it with graphics

and sound hardware closely associated with the ColecoVision lineage. In plain English: it was designed to

play games well, while also giving you a “real computer” keyboard and software story.

Graphics and sound: console DNA with computer ambitions

The Adam’s graphics capabilitiescolor, sprites, and resolutions typical of early-80s home systemswere

strong enough to make it feel “arcade-adjacent,” which was Coleco’s comfort zone. For families shopping

across consoles and computers, that hybrid identity was a selling point.

Storage: the Digital Data Pack (fast-ish… and weird)

Instead of relying on a standard floppy drive as the default, the Adam shipped with a proprietary

high-speed tape system called the Digital Data Pack. The idea was to be faster and more user-friendly than

the typical cassette workflows on other home computers. In practice, it was a mixed blessing: innovative,

but finicky, and not exactly the direction the market was trending as floppy drives became more common.

The keyboard: genuinely excellent

Even critics who roasted the Adam for its problems tended to admit the keyboard felt good. And that

matters because the Adam’s “family computer” identity wasn’t just about gamesit was about typing papers,

letters, and anything else that made parents feel like the purchase was virtuous.

Why the Adam Looked Like a Commodore 64 Rival

If you line up the Adam and the Commodore 64 on a store shelf in 1983 and squint a little, you can see

why Coleco believed. The Adam had enough computing muscle to be taken seriously, plus some advantages

that were easy to explain to non-technical buyers.

1) It sold “completeness,” not components

The Adam didn’t ask you to plan a future upgrade path. It promised a ready-to-go system right away.

That’s powerful in a market where many families were buying their first computer and didn’t want to

become part-time IT managers.

2) It leaned into education and writing

SmartWriter and the included printer made the Adam feel like the “term paper machine” with a bonus game

mode. The C64 could absolutely do productivity too, but Coleco made writing feel like the default

identitylike the machine was already waiting for your book report to show up.

3) It had a built-in bridge from console to computer

The expansion approachturn your ColecoVision into a computerwas a clean narrative: “You already own the

fun part. Now add the serious part.” In an era when families were cautious about expensive electronics,

that message could have been a winner.

Why the Commodore 64 Still Won the Living Room

Here’s the hard truth: being a “Commodore 64 competitor” didn’t just mean being comparable. It meant

surviving Commodore’s pricing strategy, its software library, and its momentum. That’s like challenging

a champion who’s allowed to change the rules mid-fight.

Price pressure: the C64 got brutally affordable

The C64’s price dropped dramatically early in its life, which changed the entire buying calculus for

families. Once a powerful computer becomes “department store” affordable, the market tilts hard in its

favorand every rival suddenly looks expensive, even if it includes extra hardware.

Software and community: the snowball effect

The Commodore 64 amassed an enormous cataloggames, utilities, educational titles, creative toolsand a

thriving culture of users and developers. That volume matters because a home computer is only as exciting

as the things you can do with it. If your friends are swapping C64 disks and talking about new releases,

it’s tough to sell them a different platform with fewer titles.

Peripherals and storage: the world was going floppy

The Adam’s tape-first story was bold, but the market was steadily moving toward disks. Tape can work,

but disks feel modern. Disks feel faster. Disks feel less like you’re negotiating with a haunted

answering machine.

The “Almost” Part: Problems That Sank a Great Pitch

The Coleco Adam didn’t fail because it lacked ideas. It failed because execution matters, and early

impressions are hard to undo. In the home-computer market, reliability wasn’t a luxury featureit was

the baseline expectation.

Production delays and limited availability

The Adam arrived later than shoppers expected and in limited quantities. That’s painful during the

holiday season, when buyers are ready to spend and retailers want predictable inventory. Miss that window,

and the momentum swings to whoever is actually on the shelf.

The notorious “tape erasure” problem

One of the Adam’s most infamous flaws was a power-related electromagnetic surge that could corrupt or

erase magnetic media if it was too close at the wrong time. That’s the kind of bug that becomes legend,

because it isn’t merely annoyingit’s actively hostile to your data. Nothing kills trust faster than a

computer that feels like it might delete your homework out of spite.

The printer-as-power-supply decision

Coleco placed the system’s power supply in the printer. So if the printer failedor wasn’t connectedthe

computer was effectively out of commission. From a tidy-cabling perspective, sure, it’s elegant. From a

real-world “my printer is acting weird” perspective, it’s like your car refusing to start because the

glove compartment is stuck.

January 1985: Coleco Pulls the Plug

By early 1985, Coleco publicly discontinued the Adam line and sold off inventory in what looked a lot

like a classic electronics fire sale. Reports at the time described substantial losses and a retreat back

toward the company’s more profitable toy businessan admission, basically, that the computer fight was

expensive and brutal.

And that’s the tragedy: the Adam was a smart concept. It anticipated what many mainstream consumers

wantedbundles, usability, immediate productivityyears before “it just works” became a marketing mantra.

But it landed in a market that rewarded reliability and punished bad first impressions with extreme

prejudice.

What Would Have Made the Adam a True Commodore 64 Challenger?

Let’s play the alternate-history game for a second. In a different timeline, the Coleco Adam doesn’t

become a cautionary taleit becomes a genuine C64 rival. What changes?

1) Rock-solid quality control from day one

If Coleco had shipped a clean first waveno headline-worthy defects, no “returns flood back to stores”

storiesthe Adam’s bundle pitch could have built trust. In consumer tech, a product with a shaky launch

often spends the rest of its life trying to convince people it’s no longer shaky.

2) A clearer storage upgrade path

If the Adam had led with a more reliable disk option (or made it a core part of the mainstream bundle),

the platform would have looked less like a detour and more like a destination. The tape system was

innovative, but the market was increasingly voting for disks with its wallet.

3) A bigger third-party ecosystem faster

The Commodore 64 wasn’t just hardwareit was a software galaxy. To compete, Adam needed more developers,

more titles, and more reasons for kids to talk about it at school besides “our printer is louder than a

lawnmower.”

Why People Still Love the Coleco Adam

Here’s the twist: the Adam may have lost the 1980s market battle, but it won something elsehistorical

fascination. Collectors and retrocomputing fans keep coming back to it because it’s unusual, ambitious, and

loaded with “what were they thinking?” design decisions that are weirdly charming in hindsight.

- It’s a true hybrid: part console ecosystem, part home computer.

- It’s a bundle time capsule: printer, word processor, controllerseverything screams 1983 optimism.

- It’s a restoration challenge: a puzzle box for hardware tinkerers and preservationists.

- It’s a lesson: great ideas still need flawless execution, especially at mass-market scale.

Modern-Day Experiences: Using a Coleco Adam Today (No Time Machine Required)

You don’t have to have grown up with a Coleco Adam to enjoy it now. In fact, approaching it fresh can be

part of the funbecause you get to experience a machine that feels like it’s auditioning for two roles at

once: “serious family computer” and “video game sidekick.”

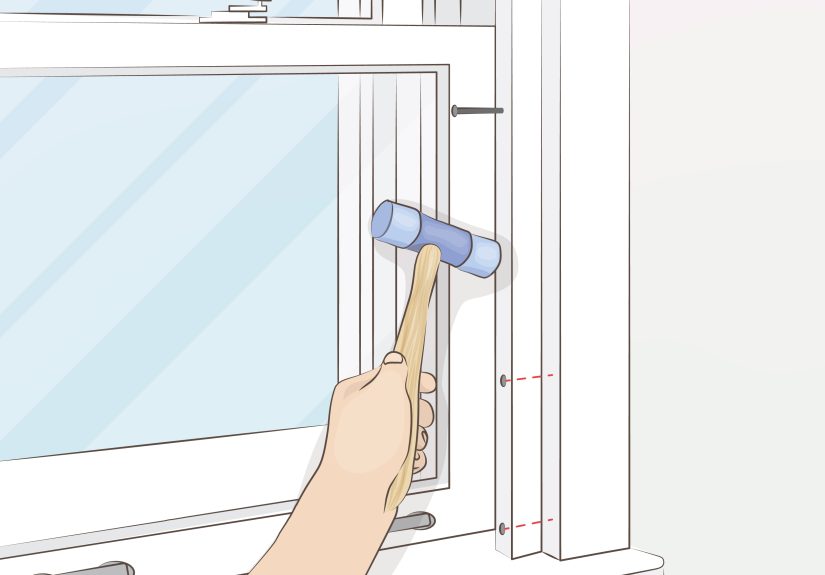

First, the setup experience is a mood. You’ll quickly learn the Adam is not a single box so much as a

polite committee of hardware: keyboard here, memory console there, printer doing double-duty as a power

station. You connect everything with a confidence that grows until you realize the printer is the

bosswithout it, the system doesn’t just lose printing. It loses existence. The Adam is basically the only home

computer that can be defeated by “paper jam.”

When you power it on, the Adam feels surprisingly immediate in its best moments. The built-in SmartWriter

word processor is the star of the show: the machine can act like an “instant typewriter,” which is

legitimately impressive for its era. You can imagine why a parent in 1983 would see this and think,

“Greatthis will help with school.” Of course, the kid is thinking, “Greatnow show me the game.”

That’s where the Adam’s identity gets charmingly conflicted. It has that ColecoVision DNA, and it wants

to reward you with arcade-style fun. But if you decide you’re a budding programmer and you want SmartBASIC,

you’ll likely experience a ritual more in line with classic home computing: loading software from tape,

waiting a bit, and hoping everything behaves. This is where modern expectations get a gentle reality check.

The Adam isn’t slow because it’s “bad.” It’s slow because it’s from an era when storage was still a

frontier and your patience was considered a valid system resource.

The sound and visuals will feel “retro console” more than “business computer,” and that’s part of the

appeal. It’s bright, it’s playful, and it makes sense that Coleco tried to sell it to families. But

you’ll also see how quickly the platform could be boxed in by practical concerns: media reliability,

hardware quirks, and the ever-present risk of troubleshooting time eating into play time. Using an Adam

today can feel like hosting a dinner party for a brilliant but temperamental guestfascinating

conversation, unpredictable behavior, and you keep the important stuff safely out of reach just in case.

And yet, when it all works, it’s easy to understand the “almost.” The Adam’s bundle concept was ahead of

its time. The keyboard feels made for real typing. SmartWriter makes productivity accessible. The console

compatibility gives it a built-in entertainment hook. If you enjoy retrocomputing for the sensation of

touching historyof seeing how designers tried to solve problems with the tools of their momentthe Adam

is a delightfully instructive machine. You don’t use it because it’s convenient; you use it because it’s

a snapshot of a bold idea that got painfully close.

Conclusion

The Coleco Adam wasn’t a joke machine. It was a real attempt to challenge the Commodore 64 with a

strategy that feels oddly modern: bundle the essentials, reduce setup friction, and make the first use

case obvious. SmartWriter-in-ROM and a printer in the box were genuinely consumer-friendly ideas.

But “almost” is doing a lot of work here. Between reliability issues, awkward design choices (hello,

printer-powered computer), and a market that was rapidly rewarding cheaper, software-rich platforms, the

Adam couldn’t recover from its earliest reputation. The Commodore 64 didn’t just compete; it

steamrolledwith price cuts, a massive library, and a thriving community.

Still, the Adam’s story is worth remembering precisely because it’s a near miss. It teaches the eternal

lesson of consumer tech: you can be visionary, you can be feature-packed, you can even be charmingbut if

you don’t ship a stable experience, the market will move on without you. Probably while you’re still

trying to load BASIC from tape.