Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- First, What Are We Even Talking About?

- Why Stocks Can Fall During a Boom (Without the Economy “Breaking”)

- 1) The stock market is a forecast, not a report card

- 2) “The economy” isn’t the same thing as “public company profits”

- 3) Interest rates can be the market’s “gravity switch”

- 4) Valuations don’t cause crashes… but they can make them easier

- 5) Leverage, positioning, and “everyone’s on the same side of the boat”

- History: When Markets Dropped Hard Even Without an Immediate Recession

- Why Booms Can Be a Breeding Ground for Crashes

- So… How Rare Is a Crash in a Boom?

- A Practical Investor’s Checklist for Boom-Time Risk

- 1) Separate “good economy” from “safe market”

- 2) Use diversification like it’s boring on purpose

- 3) Rebalance when you can, not when you’re panicking

- 4) Don’t treat valuation as a crash clock

- 5) Keep an emergency fund (so you don’t sell stocks at the worst time)

- 6) Respect leverage (especially when everything feels easy)

- If the Market Crashes During a Boom, What Should You Actually Do?

- The Bottom Line

- Real-World Investor Experiences: What This Feels Like (and What People Learn)

Picture this: the economy is humming, unemployment is low, consumers are spending, and the headlines are basically doing jazz hands. And thenbamthe stock market decides to swan-dive off a perfectly good cliff. It feels unfair, like getting dumped on your birthday by text message.

So, can the stock market crash during an economic boom? Yes. It’s not the most common combo, but it’s absolutely possible. The market and the economy are related… the way cousins are related: same family, totally different personalities, and occasionally they show up to Thanksgiving with dramatically different vibes.

In this article, we’ll break down what “boom” and “crash” really mean, why stocks can fall hard even when the economy looks strong, and what history says about the situations where “everything is fine” right up until it isn’t. We’ll finish with practical steps to keep your plan intactbecause predicting crashes is hard, but preparing for volatility is a skill you can actually learn.

First, What Are We Even Talking About?

What counts as an “economic boom”?

People use “boom” casually, but it usually means a period of strong economic growth: rising output (GDP), solid job creation, healthy consumer spending, and generally upbeat business conditions. “Boom” can also imply optimism is highsometimes a little too high.

Crash vs. correction vs. bear market

Investors toss around scary words like confetti. Let’s define them in plain English:

- Market correction: typically a drop of 10% to 20% from a recent high.

- Bear market: usually a drop of 20% or more.

- Crash: not a strict technical term, but commonly means a sharp, fast decline (often concentrated in days or weeks) that feels like the market stepped on a rake.

Important note: the economy can look “booming” while the market is correcting, and the economy can look “fine” right until it isn’tbecause economic data tends to move slower and get revised later. Stocks, meanwhile, are moody and forward-looking.

Why Stocks Can Fall During a Boom (Without the Economy “Breaking”)

1) The stock market is a forecast, not a report card

GDP and employment are backward-looking measurements of what already happened. Stocks reflect what investors think will happen next: future earnings, future interest rates, future demand, future competition, future “uh-oh” moments. That’s why the market can start dropping even while economic indicators still look great.

If the market suspects the good times are peakingmaybe profit growth will slow, or borrowing costs will riseit can reprice quickly. Think of stocks as a crowd that leaves the party early because they heard the neighbors called the cops.

2) “The economy” isn’t the same thing as “public company profits”

A booming economy doesn’t guarantee booming earnings for the companies in major indexes. Large U.S. public companies often have global revenue, exposure to currency swings, supply chain constraints, and sector-specific problems. Meanwhile, a lot of economic activity comes from areas that don’t show up neatly in stock market indexes (private businesses, nonprofits, government spending, small services).

So you can have strong GDP growth while certain sectors (or the handful of mega-companies driving the index) hit a profit wall. The economy can be jogging while the market is doing burpees in a thunderstorm.

3) Interest rates can be the market’s “gravity switch”

Even in a strong economy, markets can struggle if interest rates rise. Higher rates can:

- Increase borrowing costs for companies and consumers

- Reduce how much investors are willing to pay for future earnings (especially for high-growth stocks)

- Make safer assets like Treasuries more competitive versus stocks

Sometimes the economy is strong because conditions were easy for a whileand the natural next chapter is tighter policy. The market often reacts before the economy fully feels it.

4) Valuations don’t cause crashes… but they can make them easier

High valuations don’t automatically trigger a crash. Markets can stay expensive longer than your patience. But elevated valuations can make the market more sensitive to surprises. When expectations are sky-high, reality only needs to be slightly less perfect to create a big sell-off.

In other words: if prices already assume “everything will be amazing forever,” then “amazing but slightly less forever” can still be a problem.

5) Leverage, positioning, and “everyone’s on the same side of the boat”

Crashes often involve forced selling: margin calls, leveraged bets going wrong, risk-parity funds adjusting exposure, volatility strategies unwinding, or investors rushing for the exits at once. The economy can be fine, but the market structure can still create a stampede.

That’s one reason sudden declines can happen even without an obvious economic triggerbecause the trigger might be inside the market itself.

History: When Markets Dropped Hard Even Without an Immediate Recession

Let’s zoom in on a few examples that illustrate how markets can fall sharply even when the economy isn’t obviously falling apart at that moment.

Example #1: The 1987 crash (Black Monday) during an expansion

On October 19, 1987, the Dow fell more than 22% in a single daystill one of the most dramatic one-day drops in U.S. market history. What’s crucial for our question: this didn’t happen in the middle of a classic deep recession. The broader economy wasn’t simultaneously collapsing in real time the way many people assume when they hear the word “crash.”

This episode reminds investors that markets can have violent air pockets driven by trading dynamics, fear, and positioning. A strong economy does not provide crash insurance.

Example #2: Late 1990s strength, turbulence underneath

The late 1990s featured strong growth, surging tech optimism, and very low unemployment. Yet markets still experienced episodes of stresslike the 1998 turmoil around Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM), when a highly leveraged hedge fund’s near failure contributed to broader market instability.

That’s a “boom-with-fragility” setup: economic conditions can look healthy while financial plumbing gets risky.

Example #3: The dot-com unwind started before the economy fully rolled over

Equities peaked in 2000 and then fell sharply as the tech bubble deflated. The recession that followed (in 2001) did not begin the exact same day the market peaked. That timing gap matters: the market can fall first, and the economy can weaken lateror the economy can stay okay-ish while a wildly overvalued segment gets repriced.

The lesson: the stock market can punish overconfidence even when macro headlines still sound upbeat.

Why Booms Can Be a Breeding Ground for Crashes

Booms often come with “quiet” risk-taking

During good times, risk tends to build slowly and politelylike a cat pushing a glass toward the edge of the table. Credit expands, leverage increases, speculative narratives get louder, and people start using phrases like “this time is different” without immediately hearing alarm bells.

Policy changes can flip the mood fast

In hot economies, central banks may fight inflation by tightening financial conditions. Even if growth is still strong, markets can reprice because the future path of rates (and future earnings multiples) changes.

Expectations become brittle

When everything looks great, investors often pay up for perfection. That’s not inherently irrationaloptimism is part of markets. But perfection is fragile. A mild earnings disappointment, a sudden geopolitical shock, or a liquidity event can cause a much larger market response than you’d expect from “pretty good” economic conditions.

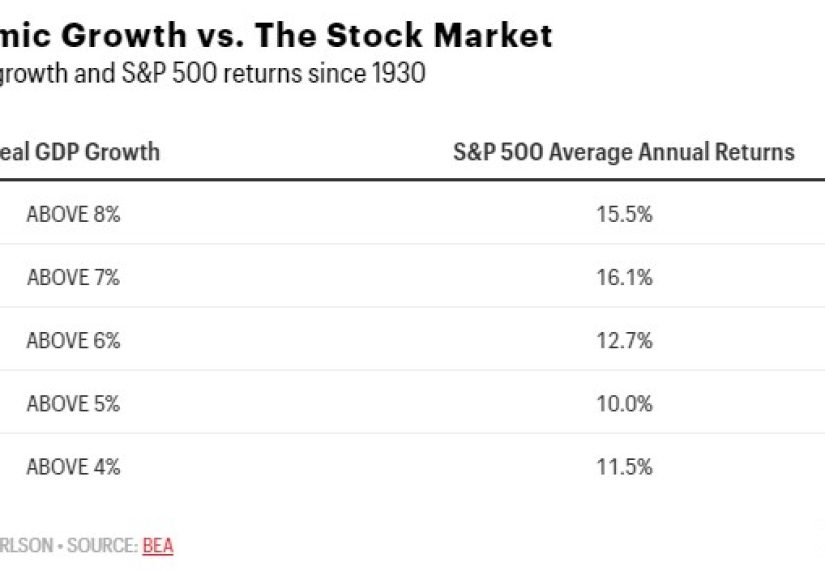

So… How Rare Is a Crash in a Boom?

It’s less common for stocks to crater while the economy is roaring, but “less common” is not “impossible.” Also, the market doesn’t need a full-blown crash to ruin your moodcorrections happen fairly regularly, even in long bull markets.

And there’s a weird twist: the market can struggle even when the economy is fine because the market was already priced for something better than fine. Stocks don’t just react to reality. They react to reality versus expectations.

A Practical Investor’s Checklist for Boom-Time Risk

1) Separate “good economy” from “safe market”

A strong economy can coexist with a fully-capable market pullback. Your plan should not assume that good GDP automatically means smooth stock returns.

2) Use diversification like it’s boring on purpose

Diversification is the broccoli of investing: not exciting, often mocked, and quietly responsible for preventing future regret. Mix across:

- U.S. and international stocks

- Large and small companies

- Stocks and high-quality bonds (based on your risk tolerance)

- Different sectors (so one trend doesn’t drive your whole outcome)

3) Rebalance when you can, not when you’re panicking

In boom times, your stock allocation can creep up because stocks are doing well. Rebalancing is the polite way of saying, “I’ll take some chips off the table.” It’s not market timing; it’s risk management.

4) Don’t treat valuation as a crash clock

Valuations can matter a lot for long-term returns, but they’re not a precise timing tool. High valuations can mean lower expected returns and more vulnerability to shocksyet markets can remain expensive for long stretches.

5) Keep an emergency fund (so you don’t sell stocks at the worst time)

The most common “forced seller” isn’t a hedge fundit’s a household hit by job loss, medical bills, or a surprise expense. An emergency fund helps you avoid turning a market dip into a permanent loss.

6) Respect leverage (especially when everything feels easy)

Leverage makes gains feel fasteruntil it makes losses feel like a trapdoor. If you’re using margin, concentrated bets, or anything that can trigger forced selling, a boom is exactly when risk hides in plain sight.

If the Market Crashes During a Boom, What Should You Actually Do?

Here’s a simple, non-dramatic response planbecause drama is expensive in investing:

- Pause: a crash makes your brain want to “do something.” Breathe first.

- Check your time horizon: money needed soon shouldn’t be in volatile assets.

- Stick to your process: keep contributing if you’re a long-term investor (dollar-cost averaging works best when it feels emotionally dumb).

- Rebalance thoughtfully: if you have a plan, a crash can be a rebalancing opportunity.

- Ignore the loudest forecast: the most confident prediction is often the least useful.

Translation: you don’t need to predict the crash; you need a plan that survives one.

The Bottom Line

Yes, the stock market can crash during an economic boom. It’s not the most common pattern, but it happens because stocks are forward-looking, valuations can be stretched, interest rates can shift, and market structure can amplify fear into a fast drop.

The most “common sense” approach is to assume that volatility can show up at inconvenient timeslike a flat tire in the rainand build your strategy around that reality: diversify, rebalance, keep cash for emergencies, avoid fragile leverage, and stay focused on the long term.

Standard disclaimer: This is educational information, not personalized financial advice. If you’re making major investment decisions, consider your goals, risk tolerance, and time horizonor talk with a qualified professional.

Real-World Investor Experiences: What This Feels Like (and What People Learn)

Even if the concept makes sense on paper, living through a market drop during “good times” is a special kind of confusing. Many investors describe it as cognitive whiplash: the economy looks fine, friends are getting promotions, restaurants are busy, and yet your portfolio is acting like it just saw a ghost.

Experience #1: “I thought good news meant stocks go up.”

A common first-time realization is that markets don’t rise because the news is goodthey rise when reality is better than expected. In boom periods, expectations often get inflated. So even a small disappointment (a company guiding slightly lower, a surprise uptick in inflation, a central bank sounding tougher) can hit stock prices hard. Investors often learn to stop treating headlines like a remote control for markets. The market isn’t a light switchit’s a crowd.

Experience #2: “I panicked, sold, and then watched it rebound.”

This is the classic painful lesson. The emotional sequence usually goes: denial (“it’s just a dip”), anxiety (“why is this still falling?”), panic (“I can’t take it”), relief-by-selling (“finally, I’m out”), and then disbelief (“why is it going back up now?”). Investors who go through this once often decide to build a clearer plan: how much risk they can tolerate, what their rebalancing rules are, and which money is truly long-term. The rebound doesn’t always happen immediately, but markets have a long history of recoveringoften before the economy “feels” fully recovered.

Experience #3: “My ‘diversified’ portfolio wasn’t actually diversified.”

In boom times, it’s easy to accidentally become concentratedespecially if one sector or a handful of mega-stocks dominate returns. Many people only discover their hidden concentration after a pullback. The practical takeaway is simple: diversification should be built intentionally (across sectors, styles, geographies, and asset types), not assumed because you own “a bunch of funds.”

Experience #4: “My emergency fund saved my investments.”

This is the underrated hero story. When markets drop, the worst-case scenario is being forced to sell due to a life expense. Investors who keep a solid cash cushion often report a surprising benefit: they feel calmer, because they’re not depending on the market to behave nicely in order to pay next month’s bills. That calm makes it easier to stay invested, keep contributing, or rebalance when prices are lower.

Experience #5: “I stopped trying to predict and started trying to endure.”

Over time, many investors shift from prediction to preparation. They accept that drawdowns happen in bull markets, corrections can appear without a recession, and “booming economy” doesn’t equal “no volatility.” The mindset change is powerful: instead of asking, “When is the crash coming?” they ask, “If a crash happens, will I be okay?” That question leads to better behavior, better planning, and fewer expensive emotional decisions.

In the end, the most useful experience investors share is this: you don’t need a perfect forecast. You need a portfolio and a process that can take a punch without you abandoning the plan.