Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “Best Practices” Means in Breast Cancer Care

- Factor 1: Screening and Time to Diagnosis

- Factor 2: Tumor Biology (Because “Breast Cancer” Isn’t One Thing)

- Factor 3: Stage, Lymph Nodes, and “Where We Start”

- Factor 4: Treatment Options and Sequencing

- Factor 5: Genomic Testing and Personalized Risk

- Factor 6: Genetics and Family History

- Factor 7: Age, Menopausal Status, Fertility, and Life Timing

- Factor 8: Other Health Conditions and Treatment Tolerance

- Factor 9: Access to Care, Insurance, and Geography

- Factor 10: Multidisciplinary Care and Shared Decision-Making

- Factor 11: Survivorship, Follow-Up, and Staying on Track

- Putting It All Together: A Best-Practices Checklist for Patients

- Conclusion

- Real-World Experiences: What People Commonly Encounter (Extra)

Breast cancer care is one of the most “choose-your-own-adventure” experiences in modern medicineexcept the

plot twists are written by biology, logistics, and real life. Two people can both have “breast cancer” and

still need totally different tests, treatments, and timelines. That’s not because doctors are indecisive;

it’s because breast cancer isn’t one single disease, and best practices are built to match the details.

This article breaks down the most important factors that can affect breast cancer carewhat they mean,

why they matter, and how patients and caregivers can use them to ask sharper questions (the kind that

make appointments more productive and less “I forgot everything the moment I sat down”).

Quick note: This is educational content, not personal medical advice. If you’re making decisions

about diagnosis or treatment, use this as a roadmap for conversations with your care team.

What “Best Practices” Means in Breast Cancer Care

“Best practices” isn’t code for “one-size-fits-all.” It’s code for “the most evidence-backed approach for

someone with your specific situation.” In breast cancer, that means following well-studied pathways:

appropriate screening, accurate staging, testing the tumor’s key features, and selecting treatments based

on risk/benefitideally through a coordinated team rather than a medical game of telephone.

Best practices usually include:

- Getting the right imaging and biopsy (so you treat the right problem).

- Confirming stage and tumor biology (so treatment fits the cancer’s “personality”).

- Using guideline-driven options (so decisions aren’t based on vibes).

- Coordinating care across specialties (so timing and sequencing actually make sense).

- Planning survivorship follow-up (because “done with treatment” is not the same as “done with care”).

Factor 1: Screening and Time to Diagnosis

The earlier breast cancer is found, the more options you typically haveand the more likely treatment can

be less intense. Screening isn’t just a checkbox; it’s a doorway to catching disease before symptoms show up.

Screening recommendations can differso be clear which guideline you’re following

For average-risk women, a widely cited U.S. recommendation is biennial screening mammography from

age 40 through 74. Other organizations may recommend annual screening or different intervals

depending on risk and values (benefits vs. false positives), but the big takeaway is: have a plan, and

don’t let “I’ll do it later” become “I found a lump.”

Dense breasts and “Why does the report sound like a warning label?”

Breast density matters for two reasons: dense tissue can make cancers harder to see on mammograms, and it’s

associated with higher risk. Many patients now receive density notifications after mammography, which can

trigger conversations about whether additional imaging (like ultrasound or MRI) is appropriateespecially

for people with higher-than-average risk.

Best-practice move: reduce delays

If an abnormal screen happens, the best practice is timely follow-up imaging andwhen neededbiopsy.

Navigation programs (more on that later) can help patients move from “suspicious finding” to “clear plan”

without months of scheduling chaos.

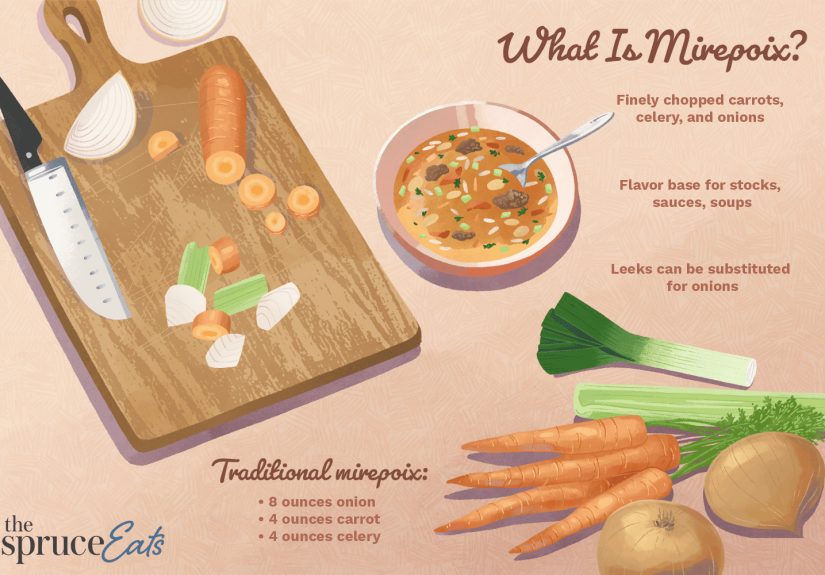

Factor 2: Tumor Biology (Because “Breast Cancer” Isn’t One Thing)

Two tumors can be the same size and in the same breast, but behave very differently based on biology.

That’s why modern care depends heavily on testing for markers that predict how a cancer grows and which

therapies can work.

The headline trio: ER, PR, and HER2

- Hormone receptor–positive (ER/PR+): Often responsive to endocrine (hormone) therapy.

- HER2-positive: Often responsive to HER2-targeted therapies.

- Triple-negative (ER-, PR-, HER2-): No hormone/HER2 targets; chemotherapy and, in some cases, immunotherapy may play a bigger role.

For hormone receptor–positive disease, endocrine therapy is a cornerstone because it can reduce the risk of

recurrence over time. Duration can varysome people take therapy for 5 years, and some may be advised to

extend longer depending on risk and tolerance. This is a classic “best practice is individualized” situation:

the goal is maximum benefit with manageable side effects.

Factor 3: Stage, Lymph Nodes, and “Where We Start”

Staging describes how much cancer is in the breast and whether it has spread to lymph nodes or beyond.

Stage influences the intensity of treatment and whether therapy should start with surgery or medication.

Why lymph nodes matter

Node involvement often raises recurrence risk and can change recommendations for chemotherapy, radiation,

and the type/length of systemic therapy. But “nodes positive” isn’t automatically “maximum chemo forever.”

Today, biology + genomic tests can refine decisions, especially for certain hormone receptor–positive cancers.

Neoadjuvant therapy (treatment before surgery) is sometimes best practice

For some subtypes (like certain HER2-positive or triple-negative cancers), starting with systemic therapy

can shrink tumors, improve surgical options, and provide early feedback on how well treatment is working.

Factor 4: Treatment Options and Sequencing

Breast cancer treatment usually combines local therapy (surgery and/or radiation) and

systemic therapy (medications that treat the whole body).

Local therapy

- Surgery: Lumpectomy or mastectomy, sometimes with lymph node evaluation.

- Radiation: Often used after lumpectomy; sometimes after mastectomy depending on risk features.

Systemic therapy

- Endocrine therapy: For hormone receptor–positive cancers (e.g., tamoxifen or aromatase inhibitors).

- Chemotherapy: More common in higher-risk disease and certain aggressive subtypes.

- Targeted therapy: Such as HER2-directed drugs when HER2 is overexpressed.

- Immunotherapy: Used in select settings, especially for some triple-negative cancers.

Sequencing is part science, part choreography. A best-practice plan considers not only what treatments are

needed, but when they should happen to maximize effectiveness and minimize complications (for example,

coordinating surgery timing with chemotherapy, or aligning radiation with reconstruction decisions).

Factor 5: Genomic Testing and Personalized Risk

For many people with early-stage, hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative breast cancer, genomic assays can

estimate recurrence risk and help predict whether chemotherapy is likely to add meaningful benefit beyond

endocrine therapy.

A common example: the Oncotype DX Recurrence Score

The Oncotype DX test analyzes gene activity in tumor tissue and returns a Recurrence Score (0–100).

Clinicians use this scorealong with age/menopausal status, node status, and other clinical factorsto guide

decisions about adjuvant chemotherapy in appropriate patients.

Best-practice mindset: avoid overtreatment when it’s unlikely to help, and don’t undertreat when risk is

truly high. Genomic tests are one of the tools that make that balancing act less guessy.

Factor 6: Genetics and Family History

Most breast cancers are not caused by inherited mutations, but a meaningful minority areoften involving

genes like BRCA1, BRCA2, and PALB2. Identifying a hereditary

mutation can influence:

- Screening strategy (e.g., earlier or MRI-added screening for high-risk individuals).

- Surgical decisions (some choose risk-reducing approaches depending on mutation and personal values).

- Systemic therapy options in certain scenarios.

- Family counseling (because genetics is a group project whether you asked for it or not).

Best practice here includes offering genetic counseling/testing when clinical criteria suggest higher risk,

and ensuring results are explained clearlybecause a lab report without guidance is just anxiety in PDF form.

Factor 7: Age, Menopausal Status, Fertility, and Life Timing

The “right” plan for a 35-year-old who wants children can look very different from the “right” plan for a

healthy 72-year-oldwithout either plan being better or worse. It’s simply context-driven medicine.

Fertility preservation is time-sensitive

For patients who want future fertility (or aren’t sure yet), best practices include discussing fertility risk

early and referring promptly to reproductive specialists when appropriate. Some fertility preservation options

need to happen before chemotherapy or certain treatments beginso delaying the conversation can reduce choices.

Menopausal status can change medication decisions

Endocrine therapy selection and supportive strategies (bone health, symptom management) often depend on whether

someone is pre- or postmenopausal.

Factor 8: Other Health Conditions and Treatment Tolerance

Best practices don’t treat the cancer in isolation. They treat the person who has the cancer. Heart disease,

diabetes, prior blood clots, osteoporosis risk, and medication interactions can influence therapy choices.

Example: Some targeted therapies have cardiac considerations, and some endocrine therapies can affect bone density.

A good plan includes baseline checks and ongoing monitoringnot to be dramatic, but because side effects are easier

to prevent than to apologize for later.

Factor 9: Access to Care, Insurance, and Geography

This is the part nobody wants to talk about, but it matters: outcomes can be influenced by access to high-quality

screening, timely diagnosis, and guideline-concordant treatment. Differences by geography, insurance coverage, and

systemic barriers contribute to cancer disparities in the U.S.

Common access issues that affect care

- Long travel distances to specialty centers (especially in rural areas).

- Delays in imaging, biopsy, or oncology appointments.

- Limited availability of genetic counseling, reconstruction, or clinical trials.

- Out-of-pocket costs that lead to skipped meds or missed follow-ups.

Patient navigation can be a best-practice “force multiplier”

Navigation programsoften led by nurses or trained navigatorscan improve timeliness and help patients complete

recommended follow-up steps. In real-world systems, this can mean fewer missed appointments, faster consults, and

less “I got bounced between five departments like a pinball.”

Factor 10: Multidisciplinary Care and Shared Decision-Making

Breast cancer care is rarely a solo sport. Best practices often involve a multidisciplinary team:

surgeons, medical oncologists, radiation oncologists, radiologists, pathologists, genetic counselors, and supportive

care professionals.

Why tumor boards exist (and why you should love that they do)

Many centers use tumor boards to review cases and align treatment recommendations across specialties. This approach

can reduce contradictory advice, improve coordination, and ensure tumor- and patient-specific factors are considered

together.

Shared decision-making: the best plan is one you can actually live with

Some decisions have “correct” answers; others have multiple reasonable options. For example:

- Lumpectomy + radiation vs. mastectomy in certain early-stage cases.

- Whether to extend endocrine therapy beyond 5 years in selected patients.

- Reconstruction timing and type.

Best practices include aligning treatment intensity with medical risk and patient preferencesbecause the

best outcomes happen when the plan makes sense clinically and fits the person’s priorities.

Factor 11: Survivorship, Follow-Up, and Staying on Track

Finishing treatment is a milestonenot an exit ramp. Follow-up care includes surveillance, managing long-term

side effects, and supporting physical and emotional recovery.

A survivorship care plan is underrated (and should not be optional)

A strong survivorship plan typically summarizes diagnosis and treatments received, outlines recommended follow-up

visits and mammograms, flags potential late effects, and clarifies who manages what (oncology vs. primary care).

Best practices also discourage unnecessary routine imaging for metastatic disease in asymptomatic early-stage survivors,

while emphasizing appropriate surveillance mammography and symptom-driven evaluation. In other words: don’t under-follow,

but also don’t over-scan out of sheer panic.

Putting It All Together: A Best-Practices Checklist for Patients

Use this as a conversation starter with your team:

- Diagnosis clarity: Do I understand my pathology (ER/PR, HER2, grade) and stage?

- Risk context: Would a genomic test help refine my chemo decision?

- Team coordination: Is my case reviewed by a multidisciplinary group or tumor board?

- Genetics: Should I meet with genetic counseling/testing based on my history?

- Life planning: Do we need to discuss fertility, menopause symptoms, work, caregiving, or travel logistics?

- Supportive care: Who helps with symptom control, mental health, nutrition, and rehab?

- Follow-up plan: Do I have a survivorship care plan in writing?

Conclusion

Best practices in breast cancer care are less about “the one perfect protocol” and more about getting the

fundamentals right: timely screening and diagnosis, accurate staging, biology-driven treatment choices,

coordinated multidisciplinary care, and a survivorship plan that supports the long game.

If there’s one power move patients can make, it’s this: ask questions that connect your diagnosis to your plan.

When you understand why a recommendation fits your specific cancer and your specific life, decisions get

clearerand the whole process becomes a little less overwhelming.

Real-World Experiences: What People Commonly Encounter (Extra)

The textbook version of breast cancer care looks clean: scan, biopsy, stage, treat, follow up. Real life is messier.

Below are experiences patients and clinicians commonly describeshared here as composite, anonymized scenarios to help

readers recognize patterns and prepare practical next steps.

1) “The waiting is worse than the test.”

Many people say the hardest stretch is the time between an abnormal mammogram and a definitive plan. It’s not just

anxietyit’s also logistics: callbacks, additional imaging, biopsies, pathology, then the first oncology appointment.

Best-practice systems try to shorten this runway, but delays still happen. What helps in the real world is treating

scheduling like a part-time job for a short season: ask for the soonest available slot, request to be placed on a

cancellation list, and don’t be shy about saying, “If there’s an opening earlier, I can come with an hour’s notice.”

2) “I got three opinions and three different plans.”

This surprises patients, but it’s often normalespecially when there are multiple reasonable options. One surgeon may

emphasize breast-conserving surgery; another may focus on reconstruction strategy; a medical oncologist may prioritize

systemic risk reduction; and a radiation oncologist will (understandably) have thoughts about radiation. A useful way

to bring order to the chaos is to ask each clinician the same three questions:

- What is the goal of this treatment (cure, risk reduction, symptom control)?

- How much benefit do you expect for someone with my stage and biology?

- What would you recommend if I were your family memberand why?

When answers are framed in goals and expected benefit, differences become easier to interpret. Sometimes the “different

plans” are just different routes to the same destination.

3) “Side effects weren’t the problem. Managing them was.”

Patients frequently report that they were warned about side effectsbut not always given a concrete plan for what to do

when side effects show up at 2 a.m. Best practices increasingly include supportive care early (not as an afterthought),

but you can advocate for it yourself. Before starting treatment, ask:

“What are the top three side effects you expect for this medication, and what’s the first-line fix for each?”

For endocrine therapy, for example, symptom management strategies can make the difference between “I quit after six

weeks” and “I stayed on therapy long enough to get the benefit.” The same goes for fatigue, nausea, neuropathy, sleep

changes, and hot flashesmany are treatable, but only if they’re addressed.

4) “Follow-up felt like falling off a cliff.”

A common emotional whiplash happens when active treatment ends. During chemo/radiation, there are frequent visits,

labs, check-ins. Then suddenly: fewer appointments, more uncertainty, and lingering side effects. People often describe

this as, “Everyone cheered, and then I went home and got scared.”

This is exactly why survivorship planning matters. Patients who do best long-term often have a written follow-up plan

(what tests happen when, what symptoms should trigger a call, who manages which medications, and how to handle bone and

heart health). If you don’t receive a survivorship care plan, ask for one explicitly. It’s not “being difficult.”

It’s being appropriately organized about your future.

5) “The most helpful person wasn’t always the doctor.”

Many patients say the turning point was meeting a nurse navigator, social worker, pharmacist, or financial counselor

someone who could translate the system, not just the science. Best practices recognize that excellent care includes

access to support for transportation, medication costs, mental health, and workplace accommodations. If your center

has navigation services, ask to be connected early. If it doesn’t, consider asking your clinic who can help coordinate

referrals and paperwork. It’s not glamorous, but it can keep treatment on track.

Real-world care is part medicine and part management. When systems are strong, they carry patients. When systems are

strained, informed patients and caregivers can still reduce friction by asking targeted questions and requesting the

right support early. The goal isn’t perfection; it’s momentumone clear next step at a time.