Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Who Paul Boyd Was to Ed, Edd n Eddy Fans

- The Night Everything Went Wrong on Granville Street

- Investigations, Inquests, and a System That Cleared Itself

- Why Cartoon Network Fans Still Can’t Let the Case Go

- Remembering Paul Boyd Beyond the Headlines

- What the Case Reveals About Police Accountability

- How Fans Are Turning Grief Into Something Constructive

- Living With the Story: Experiences From the Fandom (18 Years On)

- Conclusion: Why the Questions Still Matter

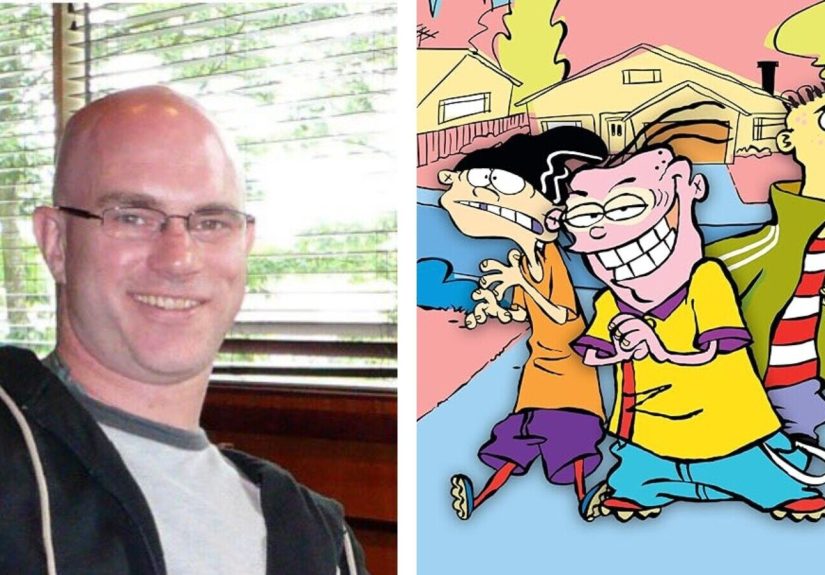

For a certain slice of Cartoon Network kids, the opening credits of Ed, Edd n Eddy are basically a core memory: the sketchy lines, the wobbly animation, the chaotic energy that promised another round of cul-de-sac mayhem. What a lot of those fans didn’t know back then is that the man who helped bring that iconic title sequence to life animator and director Paul Boyd would later die in a police shooting on a Vancouver street in 2007.

Eighteen years later, that tragedy still refuses to fade into the background. A recent feature on Cracked.com revisits the case and taps into a deep well of fan anger and confusion over why an unarmed, mentally ill animator ended up shot nine times by police and why no criminal charges were ever filed. The headline even calls Boyd the “creator” of Ed, Edd n Eddy, which isn’t technically accurate, but it does reflect how personally viewers have wrapped him into the show’s legacy.

The details of Boyd’s death, the investigations that cleared the officer, and the persistent online outrage form a story that’s part true crime, part media criticism, and part fandom grief. It’s also a painful example of how police encounters with people experiencing mental health crises can spiral into irreversible violence and how the internet can keep asking questions long after the official answers have been filed away.

Who Paul Boyd Was to Ed, Edd n Eddy Fans

First, some reality-checking. Paul G. Boyd was not the sole creator of Ed, Edd n Eddy that title belongs to animator Danny Antonucci but Boyd played a crucial role in the series’ look and feel. Born in Pasadena in 1967 and later based in Canada, he became a respected animator and director who worked at studios around Vancouver and taught at Vancouver Film School.

Boyd was a member of a.k.a. Cartoon, the team that produced Ed, Edd n Eddy for Cartoon Network. He directed and animated the show’s opening titles and contributed to its distinctive visual identity that jittery, hand-drawn vibe that made the cul-de-sac feel like it was vibrating with sugar-fueled chaos. For aspiring animators, he wasn’t just a name in the credits; he was a teacher, a mentor, and a working pro in a notoriously tough industry.

It’s telling that when Boyd died, one of the series’ episodes, “May I Have This Ed? / Look Before You Ed,” ended with a memorial card: “Paul Boyd 1967–2007. We miss you, you big lug!” That simple dedication cemented his connection to the show for a generation of viewers and it’s one reason so many Cartoon Network fans still take his death personally.

The Night Everything Went Wrong on Granville Street

On August 13, 2007, Vancouver police responded to multiple 911 calls about a disturbance on Granville Street involving a man reportedly behaving erratically and assaulting a passerby. That man was Paul Boyd. He had lived for nearly two decades with bipolar disorder, a condition those close to him say he usually managed with treatment and support.

Accounts differ on the exact sequence of events, but the broad outline is consistent across official reports and news coverage. Officers confronted Boyd, who was said to be holding an object initially described as a bicycle chain. Witnesses later disputed that description, with some saying it appeared to be a chain of paperclips hardly the classic “deadly weapon” image conjured by police narratives.

During the confrontation, Constable Lee Chipperfield fired his gun nine times. Boyd was hit repeatedly, with the final shot striking him as he lay on the ground. He died at the scene. The officer returned to work almost immediately, and, as fans would learn years later, no charges were filed.

Investigations, Inquests, and a System That Cleared Itself

If the shooting itself reads like a horrible split-second failure, the aftermath reads like a slow-motion civics lesson in how police oversight often works or doesn’t.

The Vancouver Police Department conducted the original investigation into the shooting and handed its findings off to the Criminal Justice Branch of British Columbia. In 2009, the Branch announced that no criminal charges would be approved against Chipperfield, citing insufficient evidence that he’d acted outside the law given what he claimed to perceive in the moment.

A coroner’s inquest in 2010 ruled Boyd’s death a homicide which in coroner-speak simply means “death at the hands of another,” not necessarily “murder” and issued recommendations aimed at preventing similar tragedies, including changes in training and better handling of mental health crises. Civil liberties groups and Boyd’s family argued that the inquest highlighted gaps and contradictions that hadn’t fully factored into the original decision not to prosecute.

Then, in 2012, everything flared up again. A tourist video surfaced showing the final moments of the shooting, including the ninth shot fired while Boyd appeared to be on the ground. The clip quickly circulated online and on animation sites like Cartoon Brew, igniting fresh outrage and media scrutiny.

Public pressure eventually led to the appointment of a special prosecutor to re-review the case. But in 2013, that review while critical of aspects of the shooting once again concluded there was no reasonable prospect of conviction, and no charges were laid. For Boyd’s colleagues, his family, and many fans, that outcome felt like the justice system shrugging at the death of a mentally ill animator on a public street.

Why Cartoon Network Fans Still Can’t Let the Case Go

So why is this particular police shooting still echoing around the internet nearly two decades later, resurfacing in think pieces, forum threads, and now a Cracked.com article with a headline that sounds like it was written in all-caps?

Partly, it’s because Ed, Edd n Eddy occupies a strange, beloved corner of late-’90s and early-2000s animation. It was one of Cartoon Network’s longest-running original shows, a series that never quite fit the tidy molds: ugly-cute character designs, surreal slapstick, and a tone that swung between absurd and surprisingly heartfelt. Boyd helped draw the visual door that kids walked through every time the theme song kicked in.

When fans eventually discovered that someone tied so closely to that show had been killed by police and that the case involved mental illness, multiple shots, and no charges it felt like a betrayal of the safe, silly world the series represented. Social posts memorializing Boyd still circulate every August, often emphasizing his work on the show and his struggles with bipolar disorder.

And then there’s the “creator” label. Strictly speaking, it’s incorrect Boyd was a director and animator, not the series’ creator. But in everyday fan language, the people whose work shapes a show’s identity often get folded into that term. The Cracked headline plays on that shorthand: it’s less a legal credit and more an emotional statement about how much of the show’s DNA fans see in his work.

Mental Illness, Policing, and the Gaps in Training

Another reason the case won’t die online is that it sits squarely at the intersection of two big, ongoing conversations: how police respond to mental health crises, and how many chances an officer gets before the law says, “Okay, that was too much.”

Boyd’s family has been very open about his bipolar disorder, emphasizing that he generally managed it and that the night of his death was a severe episode the kind of crisis that, ideally, would trigger specialized de-escalation tactics, not a hail of bullets. Critics argue that the number of shots fired and the final shot delivered while he was on the ground suggest a breakdown not just of tactics, but of basic proportionality.

Cases like this fuel calls for better crisis intervention training, more mental health response teams, and genuine alternatives to sending armed officers as the default option. For many readers, that broader debate is exactly why revisiting Boyd’s story still feels urgent, not just tragic.

How a 10-Second Clip Rewrote the Narrative

The late arrival of the tourist video added another layer of unease. For years, the public had essentially been asked to accept the official narrative of a dangerous suspect and a necessary use of force. Then, suddenly, grainy footage suggested a different story one where the final shot looked a lot less like “self-defense” and a lot more like overkill.

By the time that clip surfaced, no charges had been laid, and the legal machinery had mostly wrapped up its work. The re-review acknowledged the video while still landing on “no prosecution.” For fans watching from afar, it felt like a glitch in the matrix: new, disturbing evidence appears, and the system shrugs and carries on.

The Internet Refuses to Forget

The internet has a short attention span unless you give it a story that combines childhood nostalgia, unanswered questions, and a sense of injustice. Then it can hang on like a dog with a chew toy.

Boyd’s death has been discussed in YouTube retrospectives, subreddits, Facebook memorial posts, niche animation blogs, and now mainstream entertainment sites that frame it for readers who grew up on Cartoon Network. Every few years, a new wave of fans discovers the story and reacts with a familiar mix of shock, sadness, and, “How did I never hear about this?”

That recurring cycle is part of why Cracked’s 18-year retrospective hits so hard. It’s not just an article; it’s the latest chapter in a long-running, crowd-sourced investigation that lives in comment sections and social feeds as much as in official documents.

Remembering Paul Boyd Beyond the Headlines

Focusing solely on the horror of Boyd’s final moments risks flattening him into a victim and nothing more. His colleagues and family have tried to push against that, sharing stories about his humor, his work ethic, and his generosity to younger artists.

A scholarship at Vancouver Film School now honors the top student in Classical Animation, funded by his family as a way to keep his passion for the craft alive. And that episode dedication on Ed, Edd n Eddy ensures that anyone who watches through to the end is reminded that a real person, not just a name in a credit crawl, helped draw their childhood.

Fans have done their part too, creating tribute art, videos, and posts that remember Boyd as more than a headline. DeviantArt memorial pieces, social tributes marking the anniversary of his death, and fan essays about his influence on the show all add human texture to a story that official reports can’t fully capture.

What the Case Reveals About Police Accountability

Boyd’s death is far from the only controversial police shooting involving mental illness, but it’s a particularly stark example of how questions about accountability can linger long after the paperwork is done.

Supporters of the officer emphasize the chaos of the scene, the reports of assault, and the difficulty of making split-second decisions under stress. Critics point to the number of shots fired, the final shot to a prone man, the conflicting descriptions of the “weapon,” and the fact that he was in the midst of a mental health crisis. The official investigations acknowledged mistakes and raised concerns but ultimately found those problems did not meet the legal threshold for criminal charges.

For many fans reading Cracked’s coverage or diving into archived news stories, that gap between what feels obviously wrong and what the law is willing to prosecute is exactly what keeps their questions alive. It’s not just “Why did this happen?” It’s “Why did everyone who could have stopped this or punished it decide that, officially, it was acceptable?”

That frustration isn’t limited to one fandom. It speaks to a broader skepticism about whether systems designed to oversee police behavior are truly independent or are structured to give officers the benefit of every possible doubt, especially when the person who died was mentally ill, marginalized, or, in Boyd’s case, simply unlucky enough to have a breakdown in public.

How Fans Are Turning Grief Into Something Constructive

The story of Paul Boyd is unavoidably tragic, but some fans and advocates have tried to channel their anger into something more than comments and quote-tweets.

Online discussions about his death often veer into calls for better funding for mental health services, stronger crisis intervention training, and the use of unarmed response teams for non-violent calls. Some viewers who only learned about bipolar disorder through Boyd’s story have gone on to share resources, support friends, or rethink their own assumptions about “strange” behavior in public spaces.

Others have found inspiration in the way the animation community rallied around Boyd’s legacy using scholarships, tributes, and teaching to keep his work alive. For people who grew up watching Ed, Edd n Eddy, that collective response offers a model of how to mourn someone you never met: by making room for nuance, honoring their art, and refusing to let the most violent moment of their life become the only thing they’re remembered for.

Living With the Story: Experiences From the Fandom (18 Years On)

Spend enough time in the corners of the internet where Cartoon Network nostalgia lives, and you start to see the same pattern of discovery repeat like a rerun block.

It usually starts with a casual post: a screenshot of the Ed, Edd n Eddy dedication card, or a fan saying, “I just learned what happened to one of the show’s animators and I’m messed up about it.” Someone drops a link to an article or a video essay. Someone else adds a local news clip. Before long, a thread that began with “Remember this goofy show?” has turned into a kind of impromptu teach-in on mental illness, police use of force, and the thin line between “disturbance” and tragedy.

For some fans, learning about Boyd’s death becomes a privately heavy moment. One person might remember watching Cartoon Network after school as a kid, then later, as an adult, reading through legal documents and coroner’s findings on their lunch break. The cognitive dissonance is real: the same name attached to bouncy title cards is now tied to terms like “homicide ruling” and “no reasonable prospect of conviction.”

Others respond by making things. An artist might sketch the three Eds standing in front of a simple gravestone marked “Paul Boyd,” using thick, wobbling lines that echo the show’s style. A YouTube creator might splice together clips of the opening sequence with slow pans of newspaper headlines, adding a voiceover that walks viewers through what happened. A fan writer might pen a short essay about how they grew up loving the show’s chaos and now can’t watch it without thinking about who helped draw that chaos into existence and how he died.

There are also more complicated reactions. Not everyone is comfortable with the Cracked-style framing of the story, which mixes genuine outrage with punchy humor and a big, sensational headline. Some fans appreciate that tone; it feels honest to how people talk online and helps pull the story out of the dry language of official reports. Others worry that the memes and jokes might dull the seriousness of what happened, especially for readers who click away after the first paragraph.

In between those poles are people who admit, sometimes sheepishly, that they used to assume “police must have had their reasons” and only changed their minds after seeing the tourist video or reading a breakdown of the inquest findings. For them, Boyd’s case becomes a kind of mental bookmark the moment they started questioning official narratives a little harder, or looking for the perspective of families and witnesses before settling on what they believed.

Fans who live with bipolar disorder or other mental health conditions often describe a sharper, more personal reaction. The idea that a bad episode, a missed dose, or a public breakdown could end not in help but in bullets hits very close to home. For some, Boyd’s story pushes them to tell friends and family more clearly how they’d want a crisis handled: who to call, what to say, what not to do. Others say it’s the first time they saw someone like them not a criminal, not a villain, just a person with an illness framed as the victim of a system that wasn’t built to understand them.

And then there are the educators: art teachers who mention Boyd when they talk about credits and crews; media studies professors who assign articles about his death alongside episodes of the show; parents who sit down with their now-older kids and say, “Hey, you remember that cartoon you loved? Let me tell you about one of the people who worked on it, and about how the world failed him.” Those conversations don’t fix anything that happened on Granville Street in 2007. But they do something small and stubborn: they ensure that Boyd’s story continues to move forward, instead of being frozen forever in that final, horrible frame.

In that sense, the fans who can’t stop questioning what happened aren’t just rehashing old outrage. They’re doing what animation has always done best: taking a static image a memorial card, a headline, a grainy still from a tourist video and breathing movement into it. They’re letting the story keep going, not because they enjoy the pain of it, but because they recognize that letting it quietly fade out would be one more injustice layered on top of all the others.

Conclusion: Why the Questions Still Matter

Eighteen years after Paul Boyd’s death, the official story is basically complete: the reports filed, the decisions explained, the case closed. But for Cartoon Network fans, animation nerds, and anyone who has ever watched a loved one struggle with mental illness, the emotional story is very much unfinished.

Cracked’s decision to revisit the shooting isn’t just nostalgia bait or outrage fuel. It’s a reminder that the people behind our favorite shows live in the same flawed systems we do systems that often respond to crisis with force first and questions later, if at all. Remembering Boyd doesn’t mean pretending he was perfect, or turning him into a martyr. It means insisting that his life and death deserve more than a shrug and a footnote.

The kids who grew up watching Ed, Edd n Eddy are adults now. Some of them are animators, cops, therapists, lawyers, journalists, or just people who try to be slightly better bystanders than the world gave Boyd that night. If they keep asking why he died the way he did and whether our institutions could have done better that’s not obsession. That’s the bare minimum of honoring a man whose job was to breathe motion into drawings and joy into after-school TV slots.