Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- First, what heart failure actually is (and what it isn’t)

- Types of heart failure (AKA: “Which part of the pump is complaining?”)

- Symptoms: the clues your body drops (sometimes loudly)

- Common causes and risk factors

- How doctors diagnose heart failure

- Treatment options: getting the heart some backup

- Stages and classes: why your doctor uses letters and Roman numerals

- When to seek urgent help

- Living with heart failure: a practical, hopeful reality

- Frequently asked questions

- Real-life experiences: what people often go through (and what helps)

- Wrap-up

“Heart failure” is one of those phrases that sounds like a horror-movie jump scare. But medically, it doesn’t mean

your heart has stopped. It means your heart isn’t pumping (or filling) well enough to meet your body’s needs.

In other words: the pump is still running, but it’s not keeping up with demandlike a delivery driver stuck in traffic

during the holiday rush.

The good news: there are many ways to treat heart failure, reduce symptoms, and help people live longer and better.

The not-so-fun news: heart failure is common, serious, and usually chronicso it’s something you manage, not something

you “power through” with positive vibes and a third espresso.

First, what heart failure actually is (and what it isn’t)

Heart failure happens when the heart can’t pump enough oxygen-rich blood to support the body’s organs. Sometimes the

heart muscle becomes weak and can’t squeeze effectively. Other times it becomes stiff and can’t relax enough to fill

properly between beats. Both problems can lead to the same result: congestion (fluid buildup), fatigue, and reduced

exercise tolerance.

You’ll also hear the term congestive heart failure (CHF). That’s not a different diseaseit’s heart

failure that involves fluid backup and swelling (congestion), often in the lungs and lower body.

Types of heart failure (AKA: “Which part of the pump is complaining?”)

1) Left-sided heart failure

This is the most common type. The left side of the heart is responsible for pumping blood out to the entire body.

When the left side can’t keep up, blood can back up into the lungs, leading to breathing problemsespecially when

lying down or during activity.

2) Right-sided heart failure

The right side pumps blood to the lungs to pick up oxygen. When it weakens, blood backs up in the veins, often causing

swelling in the feet, ankles, legs, and sometimes the abdomen. Right-sided failure can happen on its own, but it often

develops because left-sided failure increases pressure in the lungs, which then strains the right side.

3) Biventricular (both sides) heart failure

When both sides are affected, symptoms can include a mash-up of lung congestion (shortness of breath) plus systemic

fluid retention (leg swelling, abdominal bloating), along with fatigue and weakness.

4) Heart failure by ejection fraction: HFrEF, HFpEF, and HFmrEF

Clinicians often classify heart failure by ejection fraction (EF), which is the percentage of blood

the left ventricle pumps out with each beat.

-

HFrEF (Heart Failure with reduced Ejection Fraction):

the heart’s squeeze is weaker (often called “systolic” failure). -

HFpEF (Heart Failure with preserved Ejection Fraction):

the heart’s squeeze may look “normal,” but the muscle is stiff and doesn’t fill properly (often called “diastolic” failure). -

HFmrEF (Heart Failure with mildly reduced Ejection Fraction):

a middle zone where EF is mildly reducedclinically useful because it can influence treatment decisions.

Why this matters: treatments can differ depending on the type, so it’s not just medical alphabet soup. It’s more like

picking the right toolbecause “just tighten the screw” doesn’t help if the problem is actually a leaky pipe.

5) Acute vs. chronic, and “decompensated” flare-ups

Chronic heart failure develops over time and persists long-term. Acute heart failure

can occur suddenly, or it can be a sudden worsening of chronic heart failure. A common phrase you’ll hear is

“decompensated heart failure”, which basically means the body’s coping mechanisms are overwhelmed

often showing up as rapid weight gain, swelling, and worsening shortness of breath.

Symptoms: the clues your body drops (sometimes loudly)

Heart failure symptoms can range from subtle to dramatic. Some people notice slow changes over months; others feel

worse over days. Here are common symptomsalong with what they can look like in real life:

Breathing symptoms

- Shortness of breath with activity (you’re winded on stairs that used to be easy).

- Shortness of breath when lying flat (you suddenly need extra pillows to sleep).

- Waking up gasping after a couple hours of sleep (a classic nighttime pattern for some people).

- Persistent cough, sometimes worse at night, or a “wet” cough if fluid is involved.

Fluid buildup (congestion) symptoms

- Swelling in ankles, feet, legs, or abdomen.

- Rapid weight gain over a few days (often from fluid, not “mysterious pizza weight”).

- Tight shoes or rings that suddenly feel like they shrank in the wash.

Low-perfusion / “not enough forward flow” symptoms

- Fatigue and low stamina (your “battery” feels stuck at 12%).

- Weakness or lightheadedness.

- Brain fog or trouble concentrating, especially if symptoms worsen.

- Reduced appetite, nausea, or feeling full quickly (sometimes from abdominal congestion).

Important note: these symptoms can overlap with other conditions (asthma, kidney disease, anemia, lung problems).

That’s exactly why it’s worth getting evaluated rather than self-diagnosing via vibes and an internet quiz.

Common causes and risk factors

Heart failure isn’t a single “one cause” condition. It’s usually the end result of other heart or systemic problems

that strain or damage the heart over time.

Common causes

- Coronary artery disease and prior heart attacks (damage reduces pumping strength).

- High blood pressure (the heart has to pump against higher resistance for years).

- Diabetes (affects blood vessels and heart muscle health).

- Cardiomyopathy (disease of the heart muscle).

- Heart valve disease (leaky or narrowed valves force the heart to work harder).

- Arrhythmias (irregular rhythms can weaken heart function over time).

- Congenital heart disease (structural issues present at birth).

Risk factors you can influence

- Smoking

- High sodium diet (especially if you already have risk factors)

- Physical inactivity

- Obesity

- Excess alcohol use

Not every case is preventable, but many are modifiable. Think of it like car maintenance: you can’t control every

pothole in life, but you can check the oil, rotate the tires, and avoid driving through a lake.

How doctors diagnose heart failure

Diagnosis usually combines symptom history, physical exam, and tests that assess heart structure and function.

A typical evaluation might include:

What clinicians look for on exam

- Swelling in legs/ankles

- Fluid sounds in the lungs

- Weight changes and signs of fluid retention

- Abnormal heart sounds or murmurs suggesting valve disease

Common tests

- Echocardiogram (ultrasound of the heart): evaluates EF, valve function, chamber size, wall motion.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG/EKG): checks rhythm and prior heart damage clues.

- Blood tests: may include markers that rise when the heart is under strain, plus kidney function and electrolytes.

- Chest X-ray: can show fluid in lungs or an enlarged heart silhouette.

- Stress testing or imaging: evaluates how the heart performs under load or looks for blocked arteries.

- Coronary angiography (in selected cases): checks for significant blockages.

The goal isn’t just to label “heart failure.” It’s to identify the type and the cause, because treating

what’s driving the problem can change the entire trajectory.

Treatment options: getting the heart some backup

Treatment depends on the type of heart failure, the cause, symptom severity, and other health conditions. Most plans

combine medications, lifestyle changes, and sometimes devices or procedures.

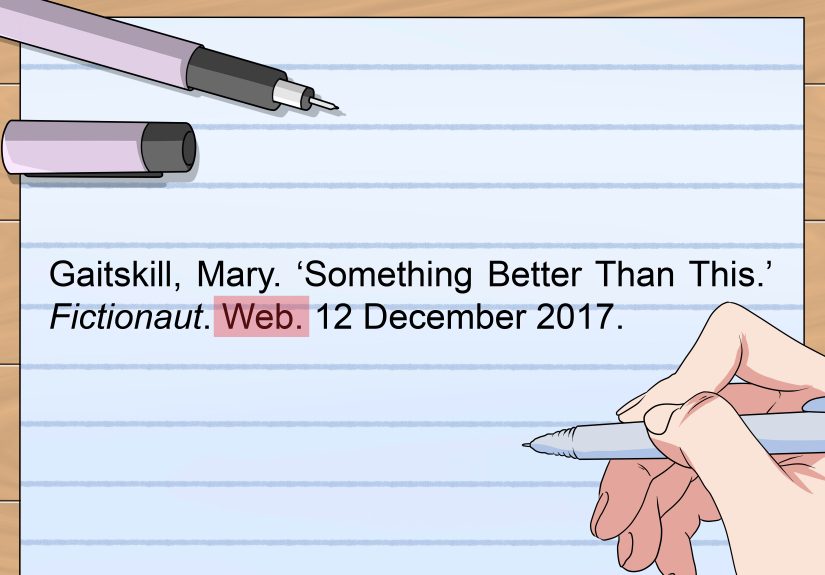

Medications (the everyday MVPs)

For many peopleespecially with HFrEFguideline-based therapy often includes several medication classes that work

together to reduce symptoms, prevent hospitalizations, and improve survival. Common categories include:

- Diuretics (“water pills”) to reduce fluid overload and ease swelling and breathlessness.

- ACE inhibitors or ARBs, and sometimes ARNIs, to reduce strain on the heart and improve outcomes.

- Beta blockers to slow the heart rate, reduce stress hormones, and support long-term heart function.

- Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) to help with fluid balance and outcomes in appropriate patients.

- SGLT2 inhibitors, originally for diabetes, now used in many heart failure patients to improve outcomes.

- Other options depending on individual needs (for example, medications for blood pressure, rhythm control, or specific populations).

Medication plans are highly individualizedso this isn’t a “pick your favorite from the list” situation. It’s a

“your clinician builds the playlist based on your heart’s genre” situation.

Devices and procedures

- ICD (implantable cardioverter-defibrillator): helps prevent sudden cardiac death in certain patients.

- CRT (cardiac resynchronization therapy): helps coordinate heart pumping when electrical timing is off.

- Revascularization (stents or bypass surgery): may help when blocked arteries are a major contributor.

- Valve repair/replacement: when valve disease is driving heart failure.

- LVAD (mechanical assist device) or heart transplant: for advanced cases when other treatments aren’t enough.

Lifestyle and self-care (small habits, big impact)

Lifestyle changes aren’t “extra credit.” They’re part of the core treatment plan. Common recommendations include:

- Tracking daily weight to catch fluid retention early.

- Managing sodium intake (salt can pull water into the bloodstream and worsen congestion).

- Staying active safely (often with cardiac rehab or a clinician-approved plan).

- Taking meds consistently (skipping doses can trigger symptom flares).

- Addressing sleep (sleep apnea is common and treatable).

- Quitting smoking and limiting alcohol.

- Controlling blood pressure, cholesterol, and diabetes.

Stages and classes: why your doctor uses letters and Roman numerals

Heart failure is often described using two overlapping systems:

Stages (A–D): the “disease progression” view

- Stage A: high risk (like high blood pressure or diabetes) but no structural heart disease yet.

- Stage B: structural heart disease present, but no symptoms yet.

- Stage C: structural heart disease with current or prior symptoms.

- Stage D: advanced symptoms despite treatment; may require specialized interventions.

NYHA Classes (I–IV): the “how limited do you feel?” view

- Class I: no limitation with ordinary activity.

- Class II: mild limitation; symptoms with ordinary activity.

- Class III: marked limitation; symptoms with less-than-ordinary activity.

- Class IV: symptoms even at rest.

These classifications help guide treatment intensity and track whether you’re improving. They’re not a personality test.

(Though if they were, Class IV would definitely be “Please stop making me walk to the mailbox.”)

When to seek urgent help

Heart failure symptoms can worsen quickly. Get urgent medical care if you have:

- Severe shortness of breath at rest, especially if it’s new or rapidly worsening

- Chest pain or pressure

- Fainting, severe dizziness, or confusion

- Pink, frothy sputum or a sudden feeling of “drowning” when breathing

- Fast, new swelling or rapid weight gain over a day or two

If you’re unsure, err on the side of getting evaluated. The “wait and see” approach is great for deciding on paint colors,

not great for breathing problems.

Living with heart failure: a practical, hopeful reality

Many people live full lives with heart failureworking, traveling, exercising, spending time with family, and doing the

things that make life feel like life. A few practical strategies often make a big difference:

- Know your baseline: weight, energy level, usual breathing tolerance.

- Have an action plan: what to do if weight jumps, swelling increases, or breathing worsens.

- Bring a buddy to appointments (another set of ears helps with medication changes).

- Protect your mood: anxiety and depression are common and treatable.

Frequently asked questions

Is heart failure the same as a heart attack?

No. A heart attack is usually caused by a sudden blockage in a coronary artery, which can damage heart muscle.

That damage can lead to heart failure, but they’re not the same condition.

Can heart failure improve?

Symptoms often improve with the right treatment plan. Sometimes, treating an underlying cause can significantly improve

heart function. Even when heart failure is chronic, many people experience long stretches of stability with good care.

Does heart failure always involve swelling?

Not always. Some people notice mostly breathing problems and fatigue. Others have prominent swelling. Symptoms depend on

the type of heart failure and how the body responds.

Why do symptoms get worse at night?

Lying flat can shift fluid back toward the chest, and the lungs may become more congested. That’s why some people need

extra pillows or wake up short of breath.

What’s the single most useful “at-home” habit?

Many clinicians point to daily weight tracking (same time each day) because sudden increases often signal

fluid retention before you feel dramatically worse.

Real-life experiences: what people often go through (and what helps)

The stories below are illustrative, anonymized composites based on common experiences people report when

they’re navigating heart failure. If you’ve never dealt with it, heart failure can feel like your body quietly changed

the rules without telling youlike you woke up to a software update and now the stairs are “premium content.”

The “Why are the stairs suddenly personal?” moment

A lot of people describe the earliest sign as a creeping loss of stamina. First it’s “I’m just out of shape,” then it’s

“Okay, I need to pause halfway up,” and then it becomes “I’m avoiding stairs like they owe me money.” What often helps

here is learning the difference between normal exertion and new shortness of breathespecially if it shows up

with mild activity or you need more pillows to breathe at night. Getting evaluated sooner can mean fewer scary moments

later, because treatment is most effective when it’s started before symptoms snowball.

The scale that tells the truth (sometimes too loudly)

One of the most practical “aha” experiences people report is realizing that fluid can show up on the scale before it

shows up in the mirror. Someone may feel fine on Monday, notice their shoes feel tight on Tuesday, and by Wednesday

they’re up several poundswithout changing what they ate. That’s often fluid retention. People who do best long-term

tend to treat the scale like an early-warning system, not a judgmental robot. Weighing daily (same time, similar clothes)

and reporting sudden gains to the care team can prevent full-blown flare-ups and ER visits.

Becoming a “salt detective” without meaning to

Many folks are surprised by how much sodium hides in everyday foodssoups, sauces, deli meats, “healthy” packaged meals,

and restaurant dishes. The experience can be frustrating at first: you feel like you need a law degree to decode labels.

Over time, people often develop a rhythmfinding lower-sodium staples they actually like, cooking a few go-to meals, and

using flavor boosters like herbs, citrus, garlic, and spices instead of salt. The win isn’t perfection; it’s consistency.

The payoff is real: less fluid retention, fewer symptoms, and fewer “why do my ankles look like they’re wearing invisible socks?” days.

Medication routines: the surprisingly emotional part

Starting multiple medications can feel overwhelming. People sometimes describe it as “my kitchen turned into a tiny

pharmacy.” A common experience is worry about side effects or frustration with frequent adjustments. What helps is

building a simple routine (pill organizer, phone reminders, linking meds to daily habits like brushing teeth) and asking

questions without embarrassment. It’s also normal for a clinician to tweak doses as your body respondsespecially with

diuretics and blood pressure–affecting meds. The emotional shift often comes when symptoms improve and the meds stop

feeling like “bad news” and start feeling like “tools that give me my life back.”

The caregiver calendar (and why support matters)

Heart failure rarely affects only one person. Partners, adult children, friendssomeone often becomes the “calendar

keeper,” tracking appointments, symptoms, and medication changes. People frequently say the best support isn’t dramatic

heroics; it’s small, steady help: driving to visits, writing down instructions, noticing subtle symptom changes, and

making sure the patient isn’t carrying the stress alone. It also helps caregivers set boundaries and avoid burnout

(because a burned-out helper is like a phone at 1% batterypresent, but one notification away from shutting down).

Many families do better when they treat management as a team sport.

If there’s a common thread across these experiences, it’s this: heart failure management works best when it’s proactive,

not reactive. Tracking symptoms, staying consistent with treatment, and communicating early with a care team can turn

“crisis cycles” into “stable stretches.” And stability is underratedit’s the quiet foundation that lets people plan,

travel, laugh, and live.

Wrap-up

Heart failure is serious, but it’s not a sentenceit’s a condition with many effective treatments and strategies.

Understanding the type (HFrEF vs HFpEF, left vs right), recognizing symptoms early, and following a tailored care plan

can dramatically improve quality of life. If you’re noticing red-flag symptomsespecially worsening shortness of breath,

swelling, or rapid weight changesgetting evaluated can be one of the most important steps you take.