Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Are Value Stocks (and Why Do People Keep Fighting About Them)?

- Why Higher Inflation Can Be a Tailwind for Value (and a Headwind for Growth)

- What the Historical Record Suggests (Without Pretending History Is a Crystal Ball)

- Sector Math: Why Value Often “Looks Like” Inflation Exposure

- The Big Caveat: Inflation Can Also Be Bad for Stocks (Especially the Wrong Kind)

- So…Should You “Buy Value” as an Inflation Strategy?

- How to Think About This Like a Grown-Up (Even If Markets Don’t Act Like One)

- FAQ: Quick Answers Investors Actually Want

- Conclusion: The Common-Sense Take

- Investor Experiences: What “Value Likes Higher Inflation” Looks Like in Real Life (500+ Words)

Inflation has a funny way of showing up uninvitedlike a distant cousin who “just needs to crash for a few months”

and then eats all your groceries while arguing about the thermostat. When inflation runs hotter, the investing

conversation usually turns into a dramatic group chat: “Rates are up!” “Bonds are down!” “My favorite growth stock

is acting like it tripped on its own valuation!”

In that chaos, value stocks often start looking suspiciously attractive. Not because they’re magical

inflation force fields (they’re not), but because higher inflation and higher interest rates tend to change what the

market rewards. This is the core idea behind Ben Carlson’s “Value Stocks Like Higher Inflation” theme from

A Wealth of Common Sense: in certain environments, value’s “boring” cash flows and cheaper valuations can

become a feature, not a bug.

Let’s unpack why that happens, what history actually says (with all the necessary caveats), and how to use this

insight without turning your portfolio into a one-factor reality show.

What Are Value Stocks (and Why Do People Keep Fighting About Them)?

Value stocks are generally companies trading at relatively “cheap” prices compared with fundamentals

like earnings, cash flow, or book value. They often have lower price-to-earnings (P/E) or price-to-book (P/B)

ratios than the market, and they frequently (not always) skew toward mature businesses that generate cash today

rather than promising cash “sometime after we colonize Mars.”

Growth stocks, by contrast, are priced more on expectations of future expansionrevenue growth,

profit growth, big market opportunities, and all the lovely narratives that make PowerPoint decks sparkle.

The “Value Premium” (a.k.a. why academics won’t let this go)

In factor investing research, “value” is often tracked through the HML factor (High Minus Low),

which represents the return difference between “high book-to-market” (cheaper/value) stocks and “low book-to-market”

(expensive/growth) stocks. Think of it as a long-running scoreboard for cheap vs. pricey. If you’ve ever wondered

why finance people say “HML” like it’s a normal word, that’s why.

Why Higher Inflation Can Be a Tailwind for Value (and a Headwind for Growth)

Here’s the intuitive version: when inflation is higher, interest rates often end up higher (or at least

investors expect them to be), and higher rates raise the discount rate used to value future cash flows.

When the discount rate rises, money you might receive far in the future is worth less today.

Ben Carlson put it in a way that sticks: growth stocks can act a bit like long-duration assetsnot exactly

bonds, but similarly sensitive to changes in rates because so much of their perceived value sits in the future.

Value stocks, which often have more cash flow happening now, can be less exposed to that “future cash flows just got

discounted harder” problem.

The “equity duration” ideahelpful, but not the whole story

A common explanation is that growth has longer “equity duration” than value. In plain English: growth’s payoff is

farther out, so it’s more rate-sensitive. That narrative is directionally useful, but some research argues the story is

more complicated because value and growth indexes rebalance over time, and that turnover changes their effective

sensitivities. Translation: rates matter, but they aren’t the only puppet master.

So the best mental model is this: higher inflation and higher rates can shift market preferences toward

cheaper valuations, current cash flows, and sectors that benefit from nominal growth. It’s less “value always wins”

and more “the scoreboard changes.”

What the Historical Record Suggests (Without Pretending History Is a Crystal Ball)

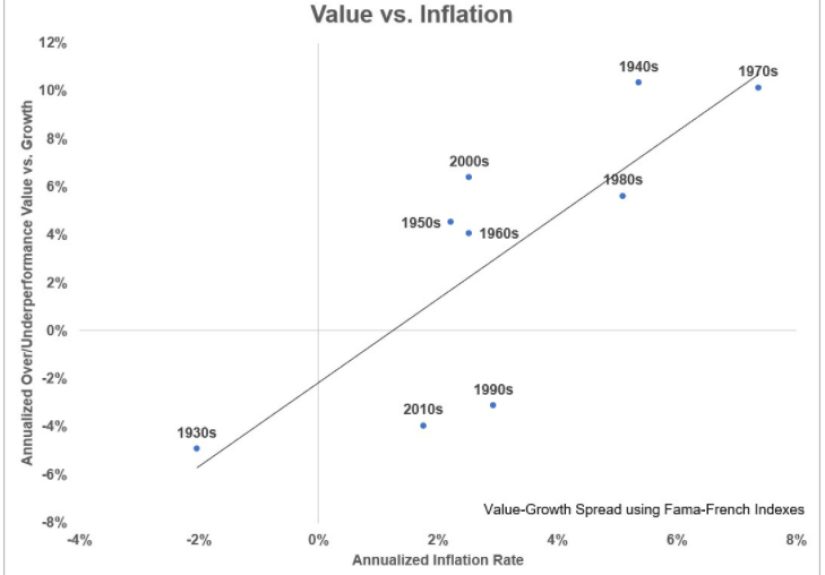

The “value likes higher inflation” claim is not that value wins every time inflation ticks up. It’s more like:

across longer regimes, value has tended to do better when inflation is higher than average, and it has tended

to struggle when inflation is low and stable.

That framing matters because markets don’t live in tidy textbook decades. They live in messy sequences of supply shocks,

policy shifts, wars, productivity booms, bubbles, crashes, and whatever else decides to show up on your news feed.

Why inflation regimes can change what “cheap” means

In low-inflation, low-rate environments, investors are often willing to pay up for long-run growth because the discount

rate is gentle. That’s one reason growth leadership has often coincided with long stretches of falling (or very low)

interest rates and tame inflation.

When inflation rises and rates follow, two things often happen at once:

- Valuation multiples compressespecially for stocks priced on far-off expectations.

-

Nominal growth picks up (not always “good” growth, but higher dollar growth), which can help certain

cyclical and value-tilted businesses.

That’s why you’ll often see value do relatively better in inflationary periodseven if the overall stock market experience

is choppier than investors would like.

Sector Math: Why Value Often “Looks Like” Inflation Exposure

Part of the value-vs.-inflation relationship is simply sector composition. Many value indexes and value

funds tend to hold more:

- Financials (banks, insurers)

- Energy (oil & gas producers, services)

- Materials (chemicals, metals)

- Industrials (manufacturing, transportation)

These groups can benefit (at least temporarily) when inflation is tied to stronger nominal demand, rising commodity prices,

or steeper rate structures. Meanwhile, growth-heavy indexes often lean toward technology and other long-duration profit

streams that can be more valuation-sensitive when rates rise.

A concrete example: when “boring” starts looking brilliant

Think about a bank versus a high-multiple software company. A bank’s business is deeply connected to interest rates and credit

conditions. Higher rates can improve net interest marginsuntil credit losses show up. A software company might have fantastic

long-term prospects, but if investors were paying a huge multiple for distant earnings, a higher discount rate can slam that

multiple down fast.

That’s the key: value often wins on valuation math and near-term cash flowsnot because value companies are

immune to inflation, but because the market’s “pricing rules” change.

The Big Caveat: Inflation Can Also Be Bad for Stocks (Especially the Wrong Kind)

Inflation isn’t automatically bullish. Moderate inflation can coexist with healthy earnings growth, but very high inflation

can squeeze consumers, destabilize margins, and force aggressive policy tightening. In other words: inflation can boost nominal

revenues while simultaneously wrecking sentiment. Finance is fun like that.

This is why serious research tends to be nuanced: stocks can do “fine” in certain inflation ranges, and they can struggle when

inflation gets extreme or when it collides with weak real growth (hello, stagflation fears).

So…Should You “Buy Value” as an Inflation Strategy?

If you’re hoping for a one-sentence answer, here it is:

Value can help diversify inflation risk, but it’s not a guaranteed hedge.

A smarter approach is to treat value as one tool in a broader toolkitespecially because the future path of inflation is

notoriously hard to predict. Even Ben Carlson’s original point wasn’t “make a macro bet,” but “notice which environments tend

to favor which styles, and diversify accordingly.”

Practical portfolio ideas (without turning this into a product pitch)

- Keep your core diversified: broad-market exposure already includes both value and growth.

- Consider a modest value tilt: a tilt is a preference, not a prophecy.

-

Rebalance instead of “react”: when value rips and growth dips (or vice versa), rebalancing forces you

to sell a little of what got expensive and buy a little of what got cheaper. - Watch for “value traps”: cheap can be a bargain, or it can be cheap for a reason.

And yes, dividends often show up more in value-y portfolios. Dividends don’t make a stock “safe,” but cash returned to investors

can feel comforting when markets are throwing tantrums.

How to Think About This Like a Grown-Up (Even If Markets Don’t Act Like One)

A durable portfolio is usually built around a few humble truths:

- You don’t control inflation.

- You don’t control interest rates.

- You definitely don’t control investor mood swings.

What you can control is your exposure to different environments. The whole “All Weather” idea in risk-parity thinking

is basically: own things that tend to do well across multiple regimes, because you don’t know what regime you’ll get next.

In a world where inflation can reappear after a long nap, value is one of the exposures that may help prevent your portfolio

from being a single-style monoculture.

FAQ: Quick Answers Investors Actually Want

Do value stocks always beat growth when inflation rises?

No. The relationship is messy. Over longer regimes, value has often looked better in higher-inflation environments, but plenty

of other forces mattervaluations, earnings cycles, policy, and whether inflation is paired with real growth or economic stress.

Are value stocks an inflation hedge like TIPS?

Not really. TIPS are designed specifically to adjust with inflation. Value stocks are still stocks: they can drop a lot, and they

can underperform for long stretches. Think “diversifier,” not “insurance policy.”

Why did growth dominate for so long?

Lower inflation and falling rates can support higher valuation multiples, which benefits long-duration cash flow stories. Add big

productivity gains and tech leadership, and growth can look unstoppableuntil the environment changes.

Conclusion: The Common-Sense Take

“Value stocks like higher inflation” is best read as a remindernot a commandment. Higher inflation can lift nominal growth and

push rates up, which often changes the market’s preferences toward cheaper valuations and current cash flows. That can create a

friendlier backdrop for value than the ultra-low inflation world that helped power growth’s dominance for years.

The most useful takeaway is not “time value perfectly.” It’s “build a portfolio that doesn’t need perfect timing.”

A little value exposure can be part of thatespecially if inflation decides to keep crashing on your couch.

Investor Experiences: What “Value Likes Higher Inflation” Looks Like in Real Life (500+ Words)

If you’ve lived through even one inflation scare, you know the experience isn’t just a chartit’s a vibe. It starts quietly:

coffee costs more, your streaming subscription “updates pricing,” and suddenly your grocery receipt looks like it’s applying for

a mortgage. You don’t need a CPI print to feel it; your wallet becomes the early-warning system.

In markets, the emotional arc often goes something like this:

first, investors argue about whether inflation is “transitory,” then they argue about whether the Fed is “behind the curve,”

and eventually they argue about whether anyone has ever truly known anything at all. During that phase, portfolios that are

loaded with high-multiple growth names can feel like they’re riding a roller coaster built by a committee of caffeinated

engineers.

This is where many investors notice the behavioral benefit of valuesometimes before they even notice the

performance benefit. Value holdings often look less exciting in booms, but in inflation-and-rate-up periods, they can feel

psychologically stabilizing because:

- They usually start cheaper, so there’s less “multiple air” underneath them.

- They often generate cash today, which makes the story easier to believe when the future gets discounted harder.

- Dividends and buybacks can act like a small reminder that you’re owning businesses, not just renting a narrative.

Another common experience: value rallies can feel “wrong” at first. If you got used to a decade where the market

rewarded long-horizon disruption stories, watching banks, industrials, energy, or “unsexy” cash-generators outperform can feel

like the market has lost its mind. It hasn’t. It’s just re-pricing risk and time. In an inflationary regime, time becomes more

expensive.

Investors also run into a practical challenge: value leadership is rarely neat. It often arrives alongside

volatility, recession chatter, and policy uncertainty. That means you can be “right” about value benefiting from inflation and

still feel uncomfortable holding it, because the headlines are screaming while your portfolio is whispering, “Please stop

checking me every 12 minutes.”

One of the most useful real-world habits people develop in these periods is rebalancing discipline. When growth

runs hot for years, it’s easy to drift into accidental concentrationyour winners become your identity. Then inflation rises,

rates rise, and suddenly the market reminds you that concentration has a personality: it’s dramatic. Rebalancingwhether quarterly,

annually, or with bandsforces a small, consistent behavior: trim what got expensive, add to what got cheaper. It’s not exciting,

but it’s how you avoid turning “value vs. growth” into a lifelong feud inside your brokerage account.

Finally, there’s the humbling experience that inflation teaches almost everyone: you don’t get to pick the regime.

You can have the world’s best thesis and still be early, late, or sideways for years. That’s why the most common “experienced”

conclusion isn’t “I’m going 100% value forever.” It’s: “I want a portfolio that can survive multiple climates.” Value exposure can

help, especially when inflation is higherbut the real win is building a plan you’ll actually stick with when the economic weather

changes again.