Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why do real Ancient Egypt facts sound fake?

- Ancient Egypt had Egyptology (yes, really)

- 81 Real Facts That Sound Absurd (But Aren’t)

- Time, history, and the ancient world’s most stubborn calendar

- Megaprojects, payroll, and the world’s earliest workplace protest

- Politics and society: Cleopatra, contracts, and an ancient peace deal

- Fun, fashion, and the ancient Egyptian talent for turning everything into symbolism

- Medicine, math, and “wait, that sounds like a textbook”

- Meteorites, mummies, and the animal afterlife economy

- Time philosophy, writing systems, and the fact that they studied their own past

- What these “absurd” facts reveal about Ancient Egypt

- Experiences: How to Get the Ancient “Wait, Really?” Feeling in Real Life

- Conclusion

If your mental image of Ancient Egypt is “pyramids, pharaohs, and a lot of sand,” you’re not wrong—you’re just

under-informed. Ancient Egypt was also: project management, workplace drama, beauty routines with surprising science,

board-game rivalries, and a calendar system that stubbornly refused to stay on time. In other words, it was a real

civilization full of real people—and that’s exactly why the most accurate facts can sound the most ridiculous.

This article rounds up 81 true Ancient Egypt facts that are documented by archaeology, museum collections,

and scholarly research—then explains why they seem absurd to modern ears. You’ll also see the big picture:

what these facts reveal about the ancient Egyptian civilization, from the Nile River economy to

mummification, hieroglyphs, and the surprisingly relatable human habit of being obsessed

with “the good old days.”

Why do real Ancient Egypt facts sound fake?

Two reasons. First, Ancient Egypt lasted so long that it’s basically multiple civilizations stacked in a trench coat.

The Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom, New Kingdom, Late Period—different eras, different rules, different vibes.

Second, we tend to imagine ancient societies as “primitive,” when they were actually specialized:

skilled administrators, engineers, artists, doctors, and scribes solving problems with the tools they had.

The result is a lot of moments that feel like time-travel whiplash:

“Wait, they had that?” and “Wait, they did that for that reason?”

Ancient Egypt had Egyptology (yes, really)

The line “Ancient Egypt itself had Egyptology” isn’t just a clever headline—it’s a real idea historians discuss.

Later Egyptians looked back at earlier monuments, repaired them, copied older texts, reused ancient styles, and sometimes

left inscriptions that amount to: “We restored this because it mattered.” One of the most famous examples is

Khaemwaset, a son of Ramesses II, remembered for restoring older monuments and later celebrated as a kind of

early “antiquities expert.” If you’ve ever fallen down a rabbit hole about the past, congratulations:

you have something in common with a royal from the New Kingdom.

81 Real Facts That Sound Absurd (But Aren’t)

Time, history, and the ancient world’s most stubborn calendar

- Ramesses II’s son Khaemwaset restored ancient monuments and became famous later as a prototype “Egyptologist.”

- Ancient Egyptians often dated documents by a king’s reign: “Year X of King Y,” like a national timestamp system.

- Early on, some years weren’t numbered at all—they were named after major events (because why be normal?).

- A national “counting” (a kind of census/tax event) helped label years: “Year of the Nth Counting.”

- They ran more than one calendar idea (civil vs. lunar tracking), because even then people argued about dates.

- The civil calendar was 12 months of 30 days plus 5 extra days tacked on at the end.

- They divided the year into three seasons: Inundation, Emergence, and Harvest.

- New Year’s Day was likely tied (originally) to the heliacal rising of Sirius and the Nile flood season.

- Because they didn’t add leap days, the civil calendar slowly drifted away from the seasons over time.

- They divided the day into 24 hours: 12 hours of daylight and 12 hours of night.

- Night “hours” were tracked using star groups called decans (astronomy as a clock face).

- There’s no clear evidence they tracked minutes or seconds the way we do—hours were the main unit.

- They used tools like sundials, shadow clocks, and water clocks to measure hours.

- Some water clocks were decorated with baboons, making “time-keeping baboons” a historically accurate phrase.

Megaprojects, payroll, and the world’s earliest workplace protest

- Huge state projects used rotating crews rather than one endless group of exhausted workers.

- Evidence suggests the Giza pyramids were built largely by paid laborers, not primarily by slaves.

- Giza had a workers’ settlement with food production and administration—basically a construction town.

- Some crews left graffiti inside monuments, including team names (ancient bragging rights).

- A harbor site at Wadi al-Jarf produced some of the oldest known papyri ever found.

- Those papyri include Merer’s logbook—a day-by-day project diary that feels shockingly modern.

- Merer describes hauling fine limestone by boat from Tura to Giza for Khufu’s pyramid casing.

- The logs describe waterways and basins used to move materials close to the building site (logistics wins wars—and pyramids).

- Coins weren’t the default paycheck; workers were often paid in rations (grain, beer, goods).

- The earliest recorded labor strike happened in Ancient Egypt.

- Royal tomb workers at Deir el-Medina protested because their food rations were late.

- The protest included a work stoppage with demands—an ancient version of “We’ll talk when you pay us.”

Politics and society: Cleopatra, contracts, and an ancient peace deal

- Cleopatra VII was Macedonian Greek (Ptolemaic), not ethnically Egyptian.

- She’s often described as the first Ptolemaic ruler known to learn the Egyptian language.

- Ancient Egyptian women could own property and make legal agreements in their own names.

- Women could also initiate divorce, which is a plot twist for anyone picturing “no rights in the ancient world.”

- Egypt’s treaty with the Hittites after Kadesh is among the earliest surviving peace treaties.

- The treaty aimed to end hostility “forever,” proving optimism is not a modern invention.

Fun, fashion, and the ancient Egyptian talent for turning everything into symbolism

- Board games were wildly popular across social classes—from royal tombs to everyday life.

- Senet was a top-tier favorite and appears in tomb art and grave goods.

- A senet board has 30 squares arranged in three rows.

- Players used casting sticks or knucklebones to determine moves (ancient dice drama included).

- People without fancy boards sometimes scratched senet grids right into stone floors.

- Senet became tied to the afterlife journey—your game night could double as spiritual metaphor.

- Tutankhamun was buried with at least five game boxes (the afterlife needed entertainment, apparently).

- Egyptians also played Twenty Squares, a game imported from the Near East and adapted locally.

- In Egypt, special squares could feature hieroglyphic designs rather than the motifs used elsewhere.

- They didn’t sleep on fluffy pillows; they used headrests made of wood or stone.

- Headrests could help protect elaborate hairstyles and improve cooling in hot climates.

- They also carried protective meanings linked to rebirth and safety during sleep.

- Some headrests feature protective deities like Bes, turning furniture into a talisman.

- Elite Egyptians wore wigs; one museum example has braids treated with beeswax and coated with animal fat.

- Some ceremonial wigs were decorated with over 1,200 gold rings (casual).

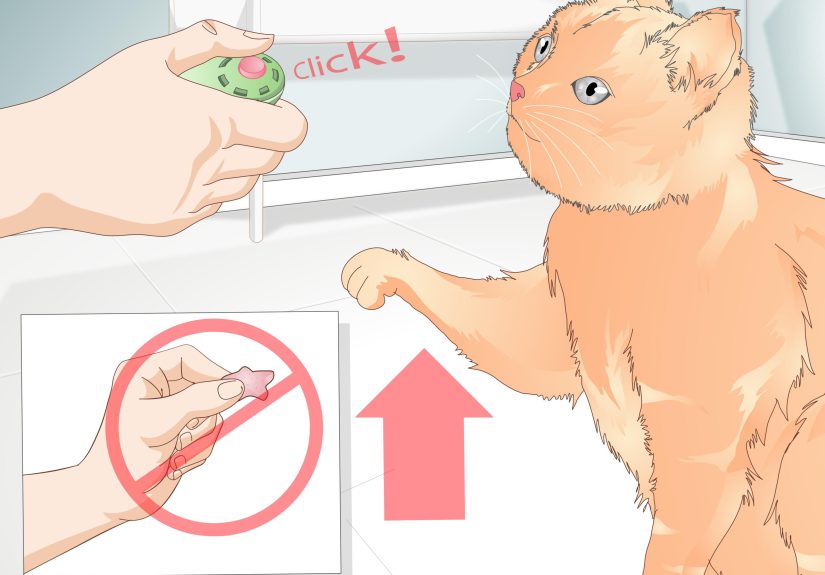

- Makeup wasn’t only cosmetic—kohl around the eyes was used by men and women and could be protective.

- Some Egyptian cosmetics included lead compounds; research suggests they may have helped reduce eye infections in certain conditions.

- Papyrus wasn’t the only “paper”—people wrote notes on ostraca (potsherds or limestone flakes).

Medicine, math, and “wait, that sounds like a textbook”

- The Ebers Papyrus (around 1500 BCE) is one of the most famous surviving medical texts from Egypt.

- It mentions willow bark for aches—a chemical cousin of aspirin’s origin story.

- The Edwin Smith Papyrus is an early trauma/surgery text with systematically described cases.

- Its structure can feel modern: observe, diagnose, and decide on treatment.

- Ancient Egyptian math leaned hard into unit fractions (fractions with 1 on top).

- Some math papyri include tables that break complex fractions into sums of unit fractions (because why use one fraction when you can use five?).

Meteorites, mummies, and the animal afterlife economy

- Meteoritic iron was valued long before iron-smelting became common.

- Some of the earliest iron artifacts in Egypt include beads made from meteorite iron.

- King Tut’s famous iron dagger is widely reported as likely made from a meteorite (high nickel content is a key clue).

- Ancient Egyptians practiced intentional mummification for thousands of years.

- Some early burials were naturally preserved by dry sand—nature’s “prototype mummy” program.

- Formal mummification used natron to dry the body.

- Linen wrappings and resins/ointments were part of the embalming toolkit.

- Materials used during mummification could be collected and buried in embalming caches as a separate sacred deposit.

- Canopic jars were used for storing certain organs during mummification (exact practices varied by era).

- Egyptians also mummified animals on a massive scale, especially as votive offerings.

- Cat mummies were commonly linked to the goddess Bastet.

- Ibis mummies were linked to Thoth, associated with writing and wisdom.

- Crocodile mummies were linked to Sobek.

- Falcon or hawk mummies were linked to Horus.

- Not every animal mummy is a perfect “one animal, one bundle” situation—some contain partial remains or substitutes.

- The offering mattered; the goal wasn’t modern zoological completeness.

Time philosophy, writing systems, and the fact that they studied their own past

- Egyptian texts describe two concepts of eternity: linear time and cyclical time.

- Cyclical time was modeled by the sun’s daily journey—death and rebirth as a cosmic schedule.

- Funerary texts offered names, spells, and guidance for navigating the afterlife (an ancient “how-to” library).

- Some spells were specifically about protecting or raising the head, showing how detailed afterlife planning could get.

- Temple-associated learning traditions included “Houses of Life,” linked to scribes and knowledge-keeping.

- Hieroglyphs can be read in different directions; a common rule of thumb is to read toward the faces of people/animals.

- Egypt used multiple scripts across time: hieroglyphs for formal display, hieratic for faster writing, and later demotic.

- The Rosetta Stone helped unlock hieroglyphs because it presented the same message in multiple scripts.

- That decipherment helped launch modern Egyptology as a formal field.

- And yes: Egyptians themselves were already studying older Egypt—repairing, copying, and preserving what they considered “ancient.”

What these “absurd” facts reveal about Ancient Egypt

Put the weirdness together and a pattern appears. Ancient Egypt was a civilization powered by

administration (dates, counts, rations, records), specialization (scribes, artisans, doctors,

builders), and a worldview where the practical and the spiritual weren’t separate categories—they were roommates.

A headrest could be furniture and protection. A board game could be entertainment and a metaphor for eternal life.

A calendar could be a civil tool and a cosmic story anchored to the Nile and the stars.

The punchline isn’t “Ancient Egypt was bizarre.” The punchline is “Ancient Egypt was human.”

When you see a labor strike, a project diary, a beauty routine, and a favorite board game, you stop thinking of the past

as a museum diorama. You start seeing it as a place where people argued, planned, worked, played, worshiped, and tried to

leave something meaningful behind. Which is—awkwardly—exactly what we’re doing now.

Experiences: How to Get the Ancient “Wait, Really?” Feeling in Real Life

Reading strange-but-true Ancient Egypt facts is fun, but the real “whoa” moment tends to hit when you experience the evidence

the way archaeologists and museum curators do: as objects, traces, and tiny details that refuse to be boring. If you ever walk

into an Egyptian gallery at a museum, you’ll notice something immediately: the past doesn’t feel silent. It feels

crowded. Not with noise, but with decisions. Someone chose how to braid hair into a wig, how to coat it, how to store it,

and why it mattered enough to bury it. Someone scratched a game board into stone because they wanted to play badly enough to

improvise. Someone carved a headrest that looks uncomfortable to us but makes total sense if your priorities are heat, hair, and

waking up without feeling like you slept in a bug hotel.

One of the best “experience hacks” for Ancient Egypt is to pick a single modern habit and follow it backward. Take timekeeping.

In your day, the clock dictates everything: school, work, deadlines, notifications. In Ancient Egypt, time still mattered—but

it was experienced differently. Hours were real, but minutes weren’t a daily obsession. Nights weren’t just darkness;

they were mapped by stars. That means when you look at a depiction of the night sky, or read about decans, you’re not just

learning astronomy trivia. You’re getting a glimpse of how it felt to live inside a world where nature and schedule were more

openly connected. The Nile floods, the seasons shift, Sirius rises again—and the calendar tries (and sometimes fails) to keep up.

That failure is oddly relatable. Humans build systems; reality laughs; we adjust.

Another powerful experience is to zoom in on bureaucracy. A papyrus logbook like Merer’s turns the Great Pyramid from an

abstract wonder into a working site with deliveries, routes, and responsibilities. Suddenly you can picture boats, storage areas,

inspections, and the unglamorous truth: monumental architecture is also paperwork. If you’ve ever worked on a group project,

you understand the emotional stakes of logistics. Now imagine the group project is made of stone and everyone is wearing linen.

If you want the most dramatic “absurd fact becomes real” moment, focus on mummification and animal offerings—not for the

spectacle, but for what it says about values. The practice required materials, time, craft knowledge, and a belief system powerful

enough to justify it. Whether you’re looking at a human mummy, an embalming cache, or an animal mummy, what you’re really

seeing is a society spending resources on meaning. It’s easy to dismiss that as superstition until you remember how many

modern resources we spend on meaning too: weddings, memorials, heirlooms, traditions, and the objects we keep because they represent

the people we love. Ancient Egyptians did that at national scale.

Finally, try experiencing Ancient Egypt like the Egyptians themselves sometimes did: with nostalgia. Think about Khaemwaset and

the impulse to restore what already seemed ancient. That’s the moment the past becomes a mirror. They weren’t only building

a future; they were curating a memory. Once you notice that, every “absurd” fact becomes more than trivia. It becomes a clue that

someone back then was thinking, “This matters. This should last.” And here you are, thousands of years later, proving them right.

Conclusion

Ancient Egypt doesn’t need myths to be fascinating. The verified facts are already wilder than most fiction:

calendars that drift, project diaries that survive, labor strikes that sound modern, and a culture that could turn a pillow into a

magical rebirth device. If you remember one thing, make it this: the ancient world wasn’t “simple.” It was different. And

different is where the best stories live.