Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Fusion Really Is (And Why the Sun Is the Ultimate Teacher)

- Why We Don’t Just Copy the Sun (A Short List of Reasons, Including “Physics”)

- Earth’s Favorite Fuel: Deuterium + Tritium

- The Sun’s Lessons, Translated Into Human Engineering

- Two Main Paths to “Bottling a Star” on Earth

- So What Exactly Is the Sun Teaching Us?

- From “Lab Win” to “Lights On”: The Hard Parts People Don’t Put on T-Shirts

- Why 2026 Feels Different: Momentum, Money, and Magnets

- What “Learning From the Sun” Looks Like in Practice

- Conclusion: We’re Not Building a SunWe’re Borrowing Its Homework

- Extra: Real-World Experiences That Make Fusion Feel Less Abstract (About )

The Sun has been running the longest, hottest, most reliable power plant in our neighborhood for about 4.6 billion years.

It doesn’t send us an instruction manual (rude), but it does send sunlightplus enough cluesfor humans to reverse-engineer

the basic trick: nuclear fusion.

Here’s the funny part: the Sun makes fusion look easy because it has two unfair advantages

gravity and time. On Earth, we don’t have a star’s worth of gravity lying around in the garage,

and our funding cycles don’t last a few billion years. So instead, we’re learning the same physics the Sun uses

and building clever machinestokamaks, lasers, superconducting magnetsthat try to create “mini-star conditions”

for long enough to produce useful energy.

What Fusion Really Is (And Why the Sun Is the Ultimate Teacher)

Fusion is the process of combining light atomic nuclei into heavier ones, releasing energy because the final nucleus is

slightly more “tightly bound” than the starting pieces. In the Sun’s core, hydrogen nuclei ultimately end up as helium,

and the energy difference becomes radiation that eventually escapes as sunlight.

The Sun’s Fusion Recipe: Pressure + Heat + Patience

In stars like our Sun, fusion happens mainly through the proton-proton (pp) chain.

Protons collide, occasionally stick, and step-by-step build helium while releasing energy and neutrinos along the way.

The Sun can do this because gravity squeezes the core to extreme pressures and temperaturesthen holds everything there

like a cosmic bench press that never skips leg day.

The big lesson: fusion isn’t “ignite and boom.” It’s a careful balance of conditions that allow enough fusion reactions

to occurfast enoughto keep the whole process going.

Why We Don’t Just Copy the Sun (A Short List of Reasons, Including “Physics”)

If the Sun’s method is “use gravity,” Earth’s method is “use engineering.” The Sun achieves fusion at mind-bending

pressures because it’s a massive sphere of plasma with gravity pulling inward from every direction.

On Earth, we have to create fusion conditions without collapsing into a star (which, to be clear, would ruin your weekend plans).

Also, the Sun gets away with relatively low fusion probability per collision because it has:

- Enormous particle density in the core

- A massive volume where reactions can happen

- Billions of years to let rare events add up

Earth-based fusion has to be much more intense and optimized because we want practical power on human timescales.

So we focus on fuel cycles that are easier to fuse than the Sun’s proton-proton chain.

Earth’s Favorite Fuel: Deuterium + Tritium

Most near-term fusion concepts aim to fuse deuterium and tritium (two isotopes of hydrogen).

This “D-T” reaction has a high probability (by fusion standards) at achievable temperaturesstill unbelievably hot, but

not “core-of-the-Sun” hot.

The tradeoff is that D-T fusion produces high-energy neutrons. Neutrons are great at carrying energy out

of the plasma (good), and also great at battering the walls of your reactor (less good).

This is why fusion is as much a materials science challenge as it is a plasma physics challenge.

The Sun’s Lessons, Translated Into Human Engineering

Lesson 1: You Need the Right “Triple Product”

Fusion research often comes back to a simple idea: you need enough

temperature, density, and confinement time.

If any one of these is too low, the plasma loses energy faster than fusion can produce it.

The Sun uses gravity to keep density high and confinement essentially continuous.

We can’t do that, so we compensate with higher temperatures and clever confinement.

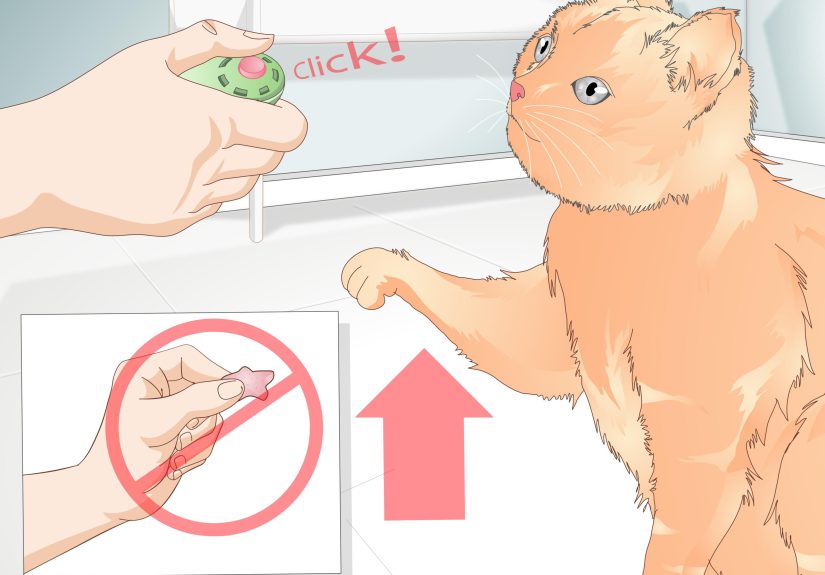

Lesson 2: Plasma Is Not a GasIt’s a Drama Queen With Opinions

Fusion fuel becomes plasma: an electrically charged soup of nuclei and electrons.

Plasma responds to magnetic fields, forms instabilities, and generally behaves like it’s trying to escape your reactor

out of pure spite. The Sun deals with plasma dynamics too (hello, solar flares), but it’s big enough that the “container”

is basically… the Sun.

On Earth, a major chunk of fusion progress is learning how to keep plasma stable, shaped, and hot without touching the walls.

Two Main Paths to “Bottling a Star” on Earth

1) Magnetic Confinement Fusion: The Tokamak Way

The most famous magnetic confinement device is the tokamaka donut-shaped machine that uses powerful

magnetic fields to confine plasma so it doesn’t touch material surfaces.

The goal is to keep the plasma hot and dense long enough for fusion reactions to occur at useful rates.

A key milestone in magnetic fusion history came from U.S. tokamak experiments that used deuterium-tritium fuel

and produced significant fusion power for short periods. These experiments helped scientists learn about

alpha particles (helium nuclei produced by fusion) and how they behave inside a plasmabecause a working fusion system

eventually needs those alpha particles to help keep the plasma hot.

Modern tokamak work is getting a boost from high-temperature superconducting magnets.

Stronger magnets can squeeze and stabilize plasma better, and they can enable more compact reactor designs.

In recent years, magnet testing has demonstrated extremely high magnetic fields at large scaleone of the key ingredients

for “smaller, sooner” fusion devices.

2) Inertial Confinement Fusion: The “Tiny Star, Tiny Time” Strategy

In inertial confinement fusion (ICF), you take a small fuel capsule and compress it so rapidly that inertia holds it together

briefly while fusion occurs. Think: squeeze a peppercorn-sized target so hard and so evenly that it turns into a micro-sun

for a fraction of a second. Easy! (That was sarcasm. It is not easy.)

The U.S. has achieved a widely reported milestone in ICF: experiments where the fusion energy released exceeded the

energy delivered to the target by the lasersa condition often called ignition in this context.

This is a scientific breakthrough, even though it’s not the same as a power plant producing net electricity.

It’s more like proving that “the physics can tip in your favor,” which is a pretty important thing to prove before you build

a machine the size of a building.

So What Exactly Is the Sun Teaching Us?

Teaching #1: Confinement Is Everything

The Sun’s confinement is gravitational and continuous. Earth’s confinement is magnetic or inertial and extremely engineered.

Either way, the principle is identical: keep the fuel together long enough for fusion to outpace losses.

Teaching #2: Symmetry Matters More Than Your Feelings

Whether you’re magnetically confining plasma in a tokamak or compressing a capsule with lasers,

small asymmetries become big problems. The Sun’s spherical gravity naturally provides symmetry.

On Earth, symmetry has to be manufactured: precise magnetic field shaping, precise laser timing, ultra-smooth capsules,

and endless diagnostics that measure everything except your stress level (though it probably could).

Teaching #3: “Hot” Is Not a NumberIt’s a Whole Lifestyle

Fusion temperatures aren’t “boiling.” They’re “electrons have left the chat.” Keeping plasma hot means limiting energy loss

through radiation, turbulence, and contact with reactor surfaces. It also means continuously heating and controlling the plasma

while it tries to kink, wobble, and burst into instabilities.

Teaching #4: Fusion Is a Systems Problem, Not a Single Breakthrough

The Sun doesn’t worry about maintenance outages. We do.

A practical fusion system must combine:

- Plasma confinement (physics)

- High-field magnets or high-power lasers (engineering)

- Materials that survive neutron bombardment (materials science)

- Tritium fuel cycle (nuclear science and supply chain)

- Heat extraction and power conversion (thermal engineering)

- Reliable operation (the part that keeps utilities from running away screaming)

From “Lab Win” to “Lights On”: The Hard Parts People Don’t Put on T-Shirts

Challenge 1: Turning Fusion Reactions Into Electricity

Even if fusion produces net energy at the reaction level, a power plant must capture that energy as heat,

move it into a working fluid, and spin a turbine (or use another conversion method).

Efficiency, maintenance, and component lifetime become just as important as plasma performance.

Challenge 2: Materials That Can Take a Beating

D-T fusion produces energetic neutrons that can damage and activate structural materials.

Designing walls, blankets, and internal components that survive long-term operation is a major R&D focus,

along with strategies to reduce downtime and simplify replacement.

Challenge 3: Tritium: Useful, Rare, and Not Something You Want to Spill

Tritium is radioactive and scarce. Many fusion designs rely on breeding tritium from lithium inside the reactor

using a “blanket” that absorbs fusion neutrons.

This is one of the biggest gaps between experiments and commercial plants:

you don’t just need fusionyou need a closed fuel cycle.

Challenge 4: Regulation and Public Confidence

Fusion isn’t fission, but it still involves radioactive materials (especially tritium) and neutron activation.

In the U.S., regulators have been working on how to license and oversee fusion systems in a way that matches their risks.

Clear rules matter because they shape timelines, costs, and how quickly a pilot plant can become a real plant.

Why 2026 Feels Different: Momentum, Money, and Magnets

Fusion progress today isn’t coming from a single lab or a single device typeit’s coming from a wider ecosystem:

national labs, universities, private startups, and large industrial partners.

Federal strategy documents in the U.S. have emphasized pathways that include public-private partnerships and a staged approach

toward a fusion pilot plant. Meanwhile, private investment has surged, partly because the world needs more

clean, firm powerand partly because data centers have turned electricity demand into a competitive sport.

The big idea is pragmatic: prove the physics, prove repeatability, then build pilot plants that demonstrate the full system

not just a beautiful plasma, but a machine that runs, breeds fuel (if needed), and makes usable power.

What “Learning From the Sun” Looks Like in Practice

If you zoom out, the Sun is teaching us three strategic truths:

- Fusion is possibleit’s not a science fiction trick. It’s natural and it works (look outside).

- Conditions matter more than slogansyou can’t “motivate” nuclei to fuse. You must meet the physics requirements.

- Stability is the real superpowerthe Sun’s greatest flex is not heat; it’s sustained operation.

Our job is to turn those truths into machines that are economical, maintainable, and safe. If that sounds like a lot,

congratulations: you have correctly identified why fusion is hard.

Conclusion: We’re Not Building a SunWe’re Borrowing Its Homework

The Sun isn’t handing us a prefab reactor design. It’s teaching the rules: confinement, stability, and energy balance.

On Earth, we translate those rules into magnets that can hold plasma without touching walls, lasers that can compress fuel

with extreme symmetry, and materials that can survive neutron-rich environments.

The path is still challenging, but it’s increasingly tangible: stronger superconducting magnets, demonstrated ignition-scale

shots in inertial confinement, clearer national strategies, and rapidly growing private-sector engineering.

The Sun’s lesson plan is longbut we’re finally doing the homework with better tools, better models, and a lot more urgency.

Extra: Real-World Experiences That Make Fusion Feel Less Abstract (About )

Fusion can sound like a faraway lab problem until you bump into it in everyday lifesometimes literally, like when you step

outside on a cold morning and the Sun hits your face with that “I pay the heating bill around here” energy.

That warmth is the end of a journey that started deep in the solar core, where tiny fusion reactions release energy that

takes ages to work its way out through layers of solar material. It’s wild to realize that the sunlight you use to find your

missing sock began as a nuclear event.

One of the easiest “fusion experiences” is visiting a planetarium or science museum with a solar exhibit.

You’ll often see animations of the proton-proton chain and models of the Sun’s layers. It’s basically the Sun saying,

“Here’s my process,” while you’re standing there holding a souvenir comet keychain.

The first time you learn that the Sun fuses hydrogen into helium not by “burning” but by nuclei sticking together,

your brain does a small backflip. It’s the moment you realize fusion isn’t just energy newsit’s the reason Earth is habitable.

Another unexpectedly memorable fusion moment is watching videos of giant magnets being tested.

Even if you don’t know a tesla from a toaster, the visuals are visceral: huge coils, heavy engineering, cryogenic systems,

and the sense that you’re looking at a technological muscle that’s being trained for a very specific jobholding plasma steady.

It feels less like abstract physics and more like watching a bridge being built, except the “bridge” is an invisible field

meant to corral something hotter than the surface of the Sun.

Then there’s the laser side of the fusion story. If you’ve ever watched slow-motion videos of precision experiments

where timing and symmetry are everythingyou’ll recognize the vibe. Inertial confinement fusion is that vibe, scaled up:

tiny targets, enormous energy delivery, and a constant battle against imperfections you can’t even see without specialized tools.

It can be strangely relatable, like trying to bake a soufflé: the recipe is real, the physics is real, and the smallest mistake

turns your masterpiece into a crater. The difference is that your soufflé doesn’t produce neutrons.

Finally, fusion becomes personal when you notice how the world talks about energy.

Data centers, electric vehicles, heat pumps, and industrial electrification are pushing demand upward,

and suddenly the question isn’t only “Can we make clean energy?” but “Can we make lots of clean energyreliably?”

That’s where fusion’s appeal clicks. You can feel why researchers and engineers keep chasing it:

not because it’s easy, but because the prizeabundant, low-carbon, firm powercould reshape how we live.

And every time you step into sunlight, you’re reminded that fusion already works. We’re just learning how to do it on purpose.