Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- French Colonial Architecture in Plain English

- Where You’ll Find French Colonial Influence in the U.S.

- Why It Looks Like That: Climate, Culture, and Common Sense

- Signature Exterior Features of French Colonial Homes

- 1) Raised living level (a.k.a. “Please don’t flood my living room”)

- 2) Full-length porches and wraparound galleries

- 3) Steep, hipped roofs with wide overhangs

- 4) Tall, narrow doors and windowsusually with shutters

- 5) Symmetrysometimes strict, sometimes “climate-first”

- 6) Materials and structure built for the region

- Signature Interior Features (Because a Breeze Needs Somewhere to Go)

- French Colonial vs. Creole vs. “French Country”: Don’t Get Tricked by the Vibes

- How to Spot a Modern “French Colonial-Inspired” Home

- Restoration and Maintenance: The Unromantic (But Useful) Truth

- Design Ideas: Borrow the Spirit Without Copying the Past

- Specific Examples That Bring the Style to Life

- Conclusion: The Style That Learned to Live With the Weather

- Real-Life Experiences With French Colonial Architecture (The Extra )

French Colonial architecture is what happens when French building traditions pack a suitcase, move to a hot,

humid, sometimes-flooding-prone place, and immediately say: “Okay, we need more shade, more airflow, and

fewer soggy floors.” The result is a style (and a family of related regional variations) known for raised living

spaces, big porches called galleries, steep roofs, tall doors and windows, and materials that can handle

real weathernot just “a light drizzle and a strong opinion.”

In the United States, French Colonial architecture is most strongly associated with Louisiana and the lower

Mississippi Valley, but it also shows up in older French settlement areas in the Midwest (the historic “Illinois

Country”). It overlaps withand is often confused withLouisiana’s Creole architecture, which is a blending of

French, Spanish, Caribbean, African, and Native influences shaped by local climate and culture.

French Colonial Architecture in Plain English

At its core, French Colonial architecture refers to buildings developed in territories influenced or governed by

France, adapted to local conditions. In North America, that often meant designing for:

- Heat + humidity (so the house can breathe)

- Heavy rain + flooding (so the house can stay dry)

- Indoor-outdoor living (because the porch becomes a lifestyle, not an accessory)

Think of it as “French practicality meets subtropical reality.” Not a dainty château momentmore like a smart,

durable, social house that knows the value of a breeze.

Where You’ll Find French Colonial Influence in the U.S.

Louisiana and the Gulf South

Louisiana is the headline act. The region’s historic homesraised cottages, plantation-era buildings, and

French Quarter-adjacent formscarry the hallmarks people associate with French Colonial style: elevated living

floors, deep porches, tall openings, and roofs designed to shed water fast. In cities like New Orleans, related

Creole building types (like the Creole cottage and Creole townhouse) also shaped the visual identity of entire

neighborhoods.

The Lower Mississippi Valley

Along the Mississippi River and its tributaries, French settlement patterns and trade routes helped spread

building traditionsthen climate and local materials did the remixing. If you’ve ever looked at a house and

thought, “This place was designed by someone who has personally argued with summer,” you’re in the right

neighborhood.

The Illinois Country (French settlements in the Midwest)

French Colonial influence also appears in older French communities in what is now Illinois and Missouri. Some

historic structures in these regions are known for vertical-log construction methods and distinctive framing

traditions that differ from the brick-and-stucco vibe many people picture in Louisiana.

Why It Looks Like That: Climate, Culture, and Common Sense

French Colonial architecture isn’t “extra” for the sake of being fancy. Many of its most recognizable features

are problem-solving disguised as style:

-

Raising the living floor helps protect the main rooms from flooding and dampness and improves

airflow underneath. - Wide galleries (porches) provide shade and create outdoor living space during long warm seasons.

- Tall doors and windows encourage cross-ventilationespecially when paired with high ceilings.

- Steep roofs move rain away quickly and can create attic space for heat to rise.

In Louisiana, these choices sit inside a broader multicultural architectural story. Creole architecture, for

example, is often described as a blend of multiple heritages responding to the demands of a hot, humid

environmentand that’s one reason the lines between “French Colonial” and “Creole” get blurry in everyday

conversation.

Signature Exterior Features of French Colonial Homes

1) Raised living level (a.k.a. “Please don’t flood my living room”)

One of the most consistent French Colonial traits in the Gulf South is a raised main floor. Sometimes the space

below is an open undercroft; other times it’s enclosed as storage, service space, or later renovations. Either

way, the idea is simple: elevate what matters.

2) Full-length porches and wraparound galleries

If you remember one word from this article, let it be gallerythe French Colonial porch tradition that’s

especially famous in Louisiana. These porches are often deep, shaded, and designed for actual use (not just a

lonely chair and a seasonal wreath trying its best).

Galleries also help protect walls and openings from intense sun and rain. And socially? They turn the house into

a friendly, outward-facing placeideal for warm evenings, conversations, and the ancient Southern ritual known as

“watching the weather.”

3) Steep, hipped roofs with wide overhangs

Many French Colonial-inspired homes have steep roofsoften hippedbuilt to dump rainwater quickly and create

shade. Wide eaves help keep walls cooler and reduce direct rain exposure around doors and windows.

4) Tall, narrow doors and windowsusually with shutters

French Colonial houses often feature tall, narrow openings that can be thrown open for airflow. Shutters are not

only a style statement; they’re functionalblocking sun, providing privacy, and offering storm protection in

regions where weather occasionally arrives with a drumline.

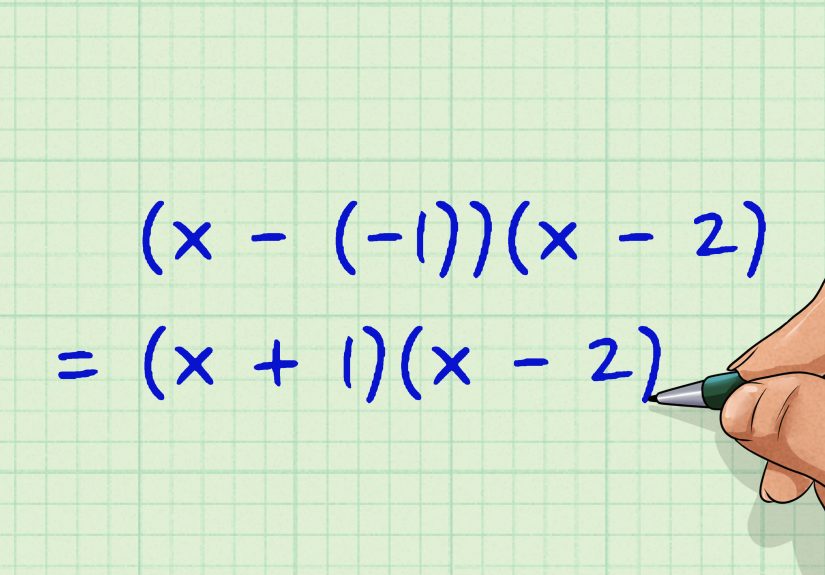

5) Symmetrysometimes strict, sometimes “climate-first”

A lot of colonial-era European design favors symmetry, and you’ll see that influence here. But regional

adaptations sometimes prioritize ventilation, shade, and circulation over perfect mirror-image facades. In other

words: the house may be balanced, but it isn’t going to lose a breeze just to look good in a math textbook.

6) Materials and structure built for the region

French Colonial construction in North America used methods and materials that could be sourced locally and

assembled efficiently. In some regions, timber framing traditions are part of the story, including distinctive

post-based construction systems and infill materials used between structural members. In Louisiana, brick

(including “brick-between-post” traditions in certain historic contexts) also appears, along with stuccoed

exteriors and wood siding depending on place and period.

Signature Interior Features (Because a Breeze Needs Somewhere to Go)

High ceilings and tall rooms

High ceilings aren’t just dramaticthey’re strategic. Hot air rises, and tall rooms help keep the occupied space

more comfortable. Combined with operable windows and doors, this creates natural ventilation that can make a

real difference in humid climates.

Room-to-porch flow (especially via French doors)

In many French Colonial-influenced Gulf Coast homes, French doors were common because they open wide, encourage

airflow, and provide easy access to galleries. This creates a strong indoor-outdoor rhythm: rooms open to the

porch, the porch connects rooms, and everyone stays cooler without needing to invent modern HVAC two centuries

early.

Flexible layouts shaped by tradition and place

Layouts vary widely depending on region, era, and cultural blending. Some related Louisiana building types

historically favored plans that support ventilation and social use, sometimes without long interior hallways.

What stays consistent is a sense that the house is designed for real living in a demanding climate.

French Colonial vs. Creole vs. “French Country”: Don’t Get Tricked by the Vibes

French Colonial vs. Louisiana Creole

Here’s the simple version: French Colonial is a broad category tied to French colonial influence and building

traditions in multiple places. Louisiana Creole architecture is a regional style that developed in and around

New Orleans and other parts of Louisiana, blending French, Spanish, Caribbean, African, and Native influences in

response to the local environment.

Because of that overlap, people sometimes use “French Colonial” as a catch-all label for older Louisiana forms.

But many preservation and local architecture references describe Creole as its own distinct styleespecially in

New Orleans.

French Colonial vs. French Provincial / French Country

French Provincial (and the broader “French Country” look) is more associated with European-inspired masonry,

formal symmetry, and decorative cues pulled from Franceoften popular in U.S. revival waves. French Colonial, by

contrast, is typically more climate-adaptive and porch-forward in the American Gulf South context.

Translation: if the house looks like it wants to host a vineyard wedding, it might be French Provincial. If it

looks like it wants to host a lemonade-and-thunderstorm party on a gallery, you’re in French Colonial territory.

How to Spot a Modern “French Colonial-Inspired” Home

Today’s builders and homeowners borrow French Colonial elements because they’re both beautiful and practical in

warm climates. A modern French Colonial-inspired house might include:

- Raised foundations (sometimes required by floodplain rules)

- Deep porches or wraparound verandas

- Hipped roofs with generous overhangs

- Tall windows and doors (often styled as French doors)

- Shutters (ideally operable, not “decorative eyelashes” nailed in place)

- Simple, balanced facades with strong horizontal porch lines

The best modern versions don’t just paste on porch columns as decorationthey keep the climate logic: shade,

airflow, and materials that can handle sun and moisture without throwing a tantrum.

Restoration and Maintenance: The Unromantic (But Useful) Truth

Historic French Colonial and Creole-influenced homes are gorgeous, but they’re not “set it and forget it.”

Practical considerations often include:

- Moisture management: keep drainage, grading, and ventilation in good shape.

- Wood care: porches, columns, and trim need regular inspection and repainting/sealing.

- Shutter function: operable shutters can be worth their weight in storm-season peace of mind.

- Historic district guidelines: places like New Orleans often have rules about exterior changes.

If you’re restoring a historic home, the goal is usually to preserve what makes it workits proportions,

openings, airflow, and materialsrather than “modernizing” it into something that fights the climate every day.

Design Ideas: Borrow the Spirit Without Copying the Past

You can capture the French Colonial feel even in a non-historic house by focusing on the features that do the

heavy lifting:

- Make the porch real: deep enough for seating, shade, and movementnot just a photo-op.

- Prioritize operable openings: windows that open wide, doors that encourage cross-breezes.

- Use shutters thoughtfully: functional shutters look better because they’re honest.

- Choose durable materials: especially in humid climatespaint systems and rot resistance matter.

- Keep rooflines simple and protective: wide eaves are both pretty and practical.

Specific Examples That Bring the Style to Life

French Colonial influence isn’t just a Pinterest categoryit’s tied to real places and real history. In the U.S.,

examples and related building types can be explored through historic neighborhoods, preservation sites, and

documented structures:

-

New Orleans-area Creole building types (cottages and townhouses) that showcase galleries,

climate adaptations, and multicultural influence. -

Raised Louisiana cottages documented in architectural surveys (including classic raised forms

associated with French Colonial influence). -

French settlement-era structures in Illinois that highlight vertical-log “post-on-sill”

construction traditions.

A quick note with a serious hat on: some well-known historic homes in the Gulf South, including plantation-era

sites, are connected to the history of enslavement. If you visit, choose tours and institutions that address

that history honestly and respectfully. Architecture is a record of beauty, yesbut also of the world that built

it.

Conclusion: The Style That Learned to Live With the Weather

French Colonial architecture is less about ornate decoration and more about smart form. Raised floors protect

against water. Galleries create shade and social space. Tall doors and windows invite airflow. Steep roofs shed

rain. In the U.S., especially in Louisiana and historic French settlement regions, the style also intersects

with Creole traditions, producing some of the most iconic, climate-savvy buildings in American architectural

history.

If you’re studying architecture, renovating an older home, or just trying to put a name to that house with the

heroic porch and the “I laugh at humidity” roofline, French Colonial architecture is a great place to start.

It’s proof that good design isn’t only about looksit’s about living well where you actually live.

Real-Life Experiences With French Colonial Architecture (The Extra )

Reading about French Colonial architecture is one thing; experiencing it is another. The first thing most people

noticewhether they’re touring a historic neighborhood in Louisiana or stepping onto the porch of a raised

cottageis how the architecture choreographs comfort. The gallery isn’t a decorative afterthought. It’s a

“second living room” that changes mood throughout the day: soft morning light, bright midday shade, and that

golden-hour glow that makes even a glass of water feel like a lifestyle choice.

In warm climates, the porch becomes an everyday habit. Homeowners often describe developing a porch routine

without trying: coffee outside because it’s cooler there, quick chats with neighbors from the steps, plants that

thrive because the overhang protects them, and evenings where the whole household migrates outdoors because the

air finally calms down. The architecture gently nudges you into a slower rhythmless “rush inside,” more “let’s

sit a minute.”

Inside, the experience is all about volume and flow. Tall ceilings and large openings make rooms feel lighter,

even when the weather is heavy. When doors and windows align, you can feel the design’s original intention:

cross-breezes that move through the house like invisible hallway traffic. It’s also why people who live in these

homes tend to become very aware of small choiceswhen to open what, how to use fans wisely, which rooms catch

the best afternoon air, and how curtains and shutters aren’t “decor,” but tools.

Visitors frequently comment on the “threshold feeling,” especially in older Louisiana homes and related Creole

forms: you’re never fully cut off from outside. The gallery is a transition zonepart shelter, part street

conversation, part private retreat. That in-between space changes how a house feels socially. You can be “home”

while still being connected to the neighborhood. It’s cozy without being closed off.

Of course, the experience comes with practical realities. Raised houses mean stairsgreat for flood protection,

less fun when you’re hauling groceries or moving furniture that absolutely refuses to pivot. Wooden elements

(porch floors, columns, railings) require attention, and people who own these homes often get good at seasonal

checkups: paint touch-ups, termite vigilance, and making sure water drains away from the foundation like it has a

personal grudge. Storm season adds another layer: shutters become meaningful, porch furniture gets secured, and

the house’s relationship with wind and rain feels very immediate.

Still, the most consistent “experience” people take away is that French Colonial architecture feels lived-in on

purpose. It’s not a style that merely poses; it performs. When you sit on a shaded gallery during a hot day, or

walk through tall doors that open wide to invite air inside, you’re feeling centuries of design decisions made

by people who needed their homes to work. And somehow, that practicality ends up being the charm.