Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What factoring a quadratic really means

- Before anything else: the one rule that saves you the most time

- 1) Factor out the Greatest Common Factor (GCF)

- 2) “Sum-Product” factoring (when a = 1)

- 3) The AC method (when a ≠ 1)

- 4) Factoring by grouping (the “four-term shuffle”)

- 5) Difference of squares (a² − b²)

- 6) Perfect square trinomials (a² ± 2ab + b²)

- 7) Factor using the zeros (quadratic formula → factors)

- Quick decision guide: which method should you try first?

- Common mistakes (and how to dodge them)

- Mini practice set (with answers)

- Real-study experiences: what factoring quadratics feels like (and how to make it easier)

- Conclusion

- SEO tags (JSON)

Factoring quadratics is basically algebra’s version of opening a locked door with seven different keys

and somehow you always try the “wrong” key first. The good news: once you know what the expression

“looks like,” you can usually pick the right key fast.

In this guide, you’ll learn 7 reliable ways to factor second degree polynomials

(also called factoring quadratics) with clear examples and a simple strategy for choosing

the best method. Along the way, we’ll keep it practical, a little funny, and very copy-paste-friendly

for homework, test prep, and real-life “why is this on the exam?” moments.

What factoring a quadratic really means

A second degree polynomial has the form ax² + bx + c where a ≠ 0.

To factor it means to rewrite it as a product, usually something like:

ax² + bx + c = a(x − r₁)(x − r₂)

When you’re solving a quadratic equation (for example, ax² + bx + c = 0),

factoring is powerful because of the zero-product rule:

if (something)(something) = 0, then at least one “something” must be zero.

One more honest detail: not every quadratic factors nicely over integers. Some are “prime” (unfactorable)

over whole numbers. That’s not a personal attack from math. It’s just… math being math.

Before anything else: the one rule that saves you the most time

Always check for a Greatest Common Factor (GCF) first.

Skipping this is like trying to assemble furniture without opening the box.

Sometimes a “hard” quadratic becomes easy after you factor out a number or a variable.

1) Factor out the Greatest Common Factor (GCF)

If every term shares a common factor (like 2, 3x, or 5y²), pull it out first.

This is the fastest win in factoring.

Example: 6x² + 9x

Both terms share a GCF of 3x.

6x² + 9x = 3x(2x + 3)

Example: 3x² − 12

The GCF is 3.

3x² − 12 = 3(x² − 4)

And now you might notice x² − 4 is a difference of squares (Method #5),

so you can keep going:

3(x² − 4) = 3(x + 2)(x − 2)

2) “Sum-Product” factoring (when a = 1)

When your quadratic looks like x² + bx + c (meaning the leading coefficient is 1),

you can factor it by finding two numbers that:

- multiply to c

- add to b

Example: x² + 7x + 10

We need two numbers that multiply to 10 and add to 7.

Those are 5 and 2.

x² + 7x + 10 = (x + 5)(x + 2)

Example: x² − 9x + 20

Multiply to 20, add to −9. That’s −5 and −4.

x² − 9x + 20 = (x − 5)(x − 4)

Quick reality check: if you can’t find a pair, the quadratic may be prime over integers,

or it might factor with fractions (less common in typical Algebra 1/2 factoring drills).

3) The AC method (when a ≠ 1)

When your quadratic is ax² + bx + c with a ≠ 1,

the AC method is the workhorse. It’s systematic and works even when guessing feels like

trying to win a staring contest with a calculator.

Steps (AC method)

- Compute a · c.

- Find two numbers that multiply to (a·c) and add to b.

- Split the middle term bx into those two parts.

- Factor by grouping (Method #4).

Example: 6x² + 7x + 2

Here, a = 6, b = 7, c = 2. So a·c = 12.

We need two numbers that multiply to 12 and add to 7:

that’s 3 and 4.

Split the middle term:

6x² + 7x + 2 = 6x² + 3x + 4x + 2

Group and factor:

(6x² + 3x) + (4x + 2) = 3x(2x + 1) + 2(2x + 1)

Factor the common binomial:

3x(2x + 1) + 2(2x + 1) = (2x + 1)(3x + 2)

Final: 6x² + 7x + 2 = (2x + 1)(3x + 2)

4) Factoring by grouping (the “four-term shuffle”)

Grouping is especially useful when:

- you already have four terms, or

- you created four terms by splitting the middle term (AC method), or

- the expression is arranged to reveal a shared binomial.

Example: 2x² + 8x + 3x + 12

Group the first two and last two:

(2x² + 8x) + (3x + 12)

Factor each group:

2x(x + 4) + 3(x + 4)

Factor out the common binomial:

(x + 4)(2x + 3)

A quick grouping tip

If grouping doesn’t create a shared binomial, try swapping the middle terms (when you split them),

or check signs. Many “grouping fails” are really “sign mistakes wearing a disguise.”

5) Difference of squares (a² − b²)

If you see two perfect squares separated by a minus sign, you’ve found a shortcut:

a² − b² = (a + b)(a − b)

This method is common in factoring polynomials and shows up constantly in quadratic expressions,

especially after you factor out a GCF first.

Example: x² − 16

Both terms are perfect squares: x² and 16 = 4².

x² − 16 = (x + 4)(x − 4)

Example: 9x² − 25

9x² = (3x)² and 25 = 5².

9x² − 25 = (3x + 5)(3x − 5)

Pro move: “Factor to produce” a difference of squares

Sometimes you can create a difference of squares by factoring a GCF:

12x² − 48 = 12(x² − 4) = 12(x + 2)(x − 2)

6) Perfect square trinomials (a² ± 2ab + b²)

Perfect square trinomials come from squaring a binomial. They look like:

- a² + 2ab + b² = (a + b)²

- a² − 2ab + b² = (a − b)²

How to recognize them

- First term is a perfect square.

- Last term is a perfect square.

- Middle term is ±2ab (twice the product of the square roots).

Example: x² + 10x + 25

x² is a square, 25 = 5², and the middle term 10x

equals 2·x·5.

x² + 10x + 25 = (x + 5)²

Example: 4x² − 12x + 9

4x² = (2x)², 9 = 3², and −12x = −2·(2x)·3.

4x² − 12x + 9 = (2x − 3)²

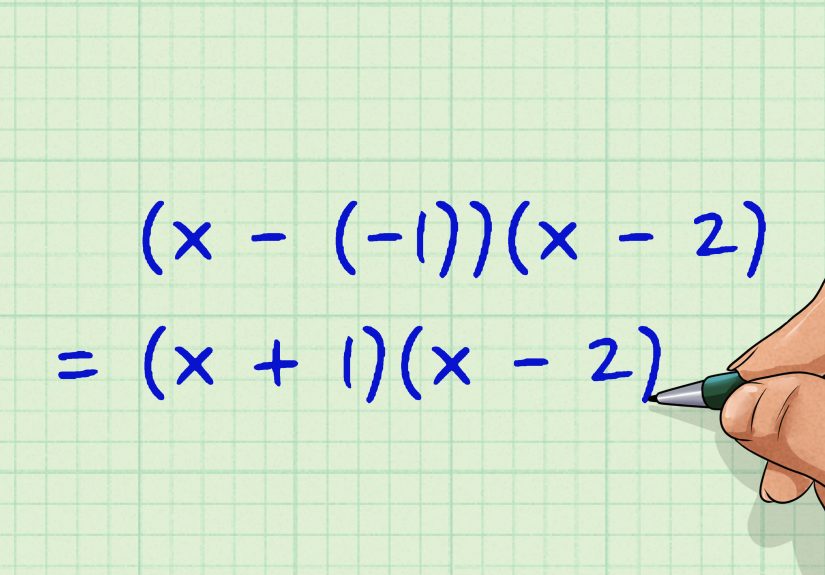

7) Factor using the zeros (quadratic formula → factors)

If the quadratic doesn’t factor nicely (or you just want a guaranteed path),

you can find its zeros and build the factorization from them.

This is the “no matter what, I’m getting out of here” method.

Step-by-step

- Solve ax² + bx + c = 0 using the quadratic formula.

- Let the solutions be r₁ and r₂.

- Then ax² + bx + c = a(x − r₁)(x − r₂).

Example: 2x² + x − 1

This one actually factors by inspection, but it’s a good demo.

Using factoring quickly: we want (2x ?)(x ?) with product −1. Try:

(2x − 1)(x + 1).

Multiply to check: 2x² + 2x − x − 1 = 2x² + x − 1. Works.

2x² + x − 1 = (2x − 1)(x + 1)

Example: x² + x + 1 (doesn’t factor over real numbers)

The discriminant is b² − 4ac = 1 − 4 = −3, which is negative.

That means there are no real roots, so it won’t factor into real binomials.

Over complex numbers, it factors using complex roots:

x = (−1 ± i√3)/2.

Translation: if your assignment is “factor over the integers,” then

x² + x + 1 is prime and you’re done. If the assignment is “factor completely,”

you might be expected to use complex numbers.

Quick decision guide: which method should you try first?

When you’re staring at a quadratic polynomial like it owes you money, use this checklist:

- GCF? If every term shares a factor, pull it out. (Method #1)

- Two terms? Check difference of squares. (Method #5)

- Three terms?

- If a = 1, use sum-product. (Method #2)

- If a ≠ 1, use AC method. (Method #3 → #4)

- If it matches a perfect-square pattern, use Method #6.

- Does nothing work? Use roots (quadratic formula) to factor or confirm it’s prime (over integers). (Method #7)

- Always verify by multiplying your factors back out (FOIL or distribution).

Common mistakes (and how to dodge them)

- Forgetting the GCF: You “can’t factor” it… until you factor out 2 or 3 and it becomes easy.

- Sign slips: If c is positive and b is negative, both numbers must be negative in Method #2.

- AC method pairing errors: Your two numbers must multiply to ac and add to b.

- Not checking: Multiplying back takes 10 seconds and can save 10 points.

- Assuming everything factors nicely: Some quadratics are prime over integers. That’s normal.

Mini practice set (with answers)

Try these to build factoring confidence:

- 8x² + 12x

- x² − 49

- x² + 11x + 24

- 3x² + 10x + 8

- 4x² − 20x + 25

- 2x² + 3x + 5 (factor over the reals?)

Answers

- 8x² + 12x = 4x(2x + 3)

- x² − 49 = (x + 7)(x − 7)

- x² + 11x + 24 = (x + 3)(x + 8)

- 3x² + 10x + 8 = (3x + 4)(x + 2)

- 4x² − 20x + 25 = (2x − 5)²

-

2x² + 3x + 5 has discriminant 9 − 40 = −31, so it does not factor over the reals.

Over complex numbers it can be written using complex roots.

Real-study experiences: what factoring quadratics feels like (and how to make it easier)

Most people don’t struggle with “quadratics” so much as they struggle with the moment of choice:

you open the problem, see ax² + bx + c, and your brain asks,

“Okay… which method is today’s method?” That uncertainty is a totally normal part of learning

factoring second degree polynomials. The trick is to turn method-picking into a habit, not a vibe.

A common experience students report is that factoring feels randomuntil they start running a short checklist.

Once you train yourself to always scan for a GCF first, then count terms, then look for special patterns,

your success rate jumps fast. It’s like learning to spot your car in a parking lot:

at first everything looks the same, and then suddenly you notice the red bumper sticker (difference of squares)

or the roof rack (perfect square trinomial) and you’re done.

Another very real pattern: the first few times you try the AC method, it feels slow and mechanical.

That’s actually the point. “Mechanical” is a feature, not a bugbecause on test day your brain is busy

managing time, nerves, and that one classmate who finishes everything in seven seconds.

The AC method gives you a dependable workflow: multiply a·c, find the pair that adds to b,

split the middle, group, factor. After you do it enough, you stop thinking about the steps and start seeing

them as one move.

People also tend to have a specific “factoring nightmare”: the sign mistake. You do everything right,

but one plus becomes a minus, and your final check doesn’t match. The best experience-based fix is simple:

always verify by multiplying back. Not because your teacher loves busywork, but because

FOIL/distribution is the fastest lie detector in algebra. You don’t have to be perfect; you just have to be

willing to check.

And here’s a confidence booster that doesn’t get said out loud enough: sometimes your struggle is not

“I can’t factor” but “this quadratic doesn’t factor over integers.” When that happens, it’s easy to think

you’re missing something. You’re not. Use the discriminant (b² − 4ac) or the quadratic formula

as a reality check. If the discriminant isn’t a perfect square (and especially if it’s negative), the expression

won’t factor cleanly into integer binomials. Knowing that is a skill. It saves time and prevents you from

trying to force a factorization that doesn’t exist.

Finally, the most useful “experience” tip for long-term improvement: keep a tiny practice routine.

Two or three problems a day beats twenty problems once a week. Mix the typesone GCF, one difference of squares,

one trinomial with a ≠ 1. Your brain learns factoring quadratics by contrast. Over time, you’ll stop

memorizing and start recognizing. That’s when factoring goes from “ugh” to “oh, I see it.”

Conclusion

Factoring quadratics isn’t one skillit’s a toolbox. Start with the GCF, scan for special patterns like

difference of squares and perfect square trinomials, and use sum-product or the AC method for trinomials.

When factoring gets messy, use the zeros to confirm whether it factors nicely or not.

And remember: the goal isn’t to guess perfectly. The goal is to choose a method confidently, work the steps,

and check your result like a responsible adult (or at least like someone who wants full credit).