Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What a Bank Statement Really Is (and Why It Matters)

- Step 1: Start at the TopThe “Statement Header” Tells You the Rules

- Step 2: Understand the Account SummaryYour Month in One Snapshot

- Step 3: Learn the Two Dates That Cause Most Confusion

- Step 4: Decode the Transaction ListWhere the Story Actually Lives

- Step 5: Pay Special Attention to FeesThey’re Small Until They’re Not

- Step 6: Understand ACH, Direct Deposit, and Auto-Pay (Because They Run Your Life)

- Step 7: Reconcile Your Statement in 10–15 Minutes (Yes, Really)

- Step 8: How to Spot Errors and Fraud Using Your Statement

- Step 9: Make Your Statement Work for You (Budgeting, Goals, and “Subscription Creep”)

- Step 10: Know What to Save (and What to Shred)

- Step 11: A Quick “Statement Confidence” Routine You Can Repeat Monthly

- Real-World Experiences: The Statement Mysteries People Actually Run Into (Extra )

- 1) The Gas Station Charge That Looks Wrong (But Isn’t… Yet)

- 2) The Merchant Name That Sounds Like a Sci-Fi Villain

- 3) The “I Didn’t Overdraft” Overdraft

- 4) The Missing Paycheck That Wasn’t Missing

- 5) The Refund That Took Forever

- 6) The Duplicate Charge That Was Actually Two Transactions

- 7) The Tiny Charge That Saved Them from a Big One

- Conclusion

Your bank statement is basically your money’s group chat: every deposit, every purchase, every fee that popped in uninvited, and every “who even is

POS DEBIT XYZ?” momentcaptured in one monthly (or quarterly) recap.

And unlike group chats, your bank statement doesn’t do sarcasm. It’s brutally honest. Which is exactly why learning to read it is one of the quickest

ways to catch mistakes, avoid fees, spot fraud early, and actually understand where your money is goingwithout needing a finance degree or a spreadsheet

addiction.

What a Bank Statement Really Is (and Why It Matters)

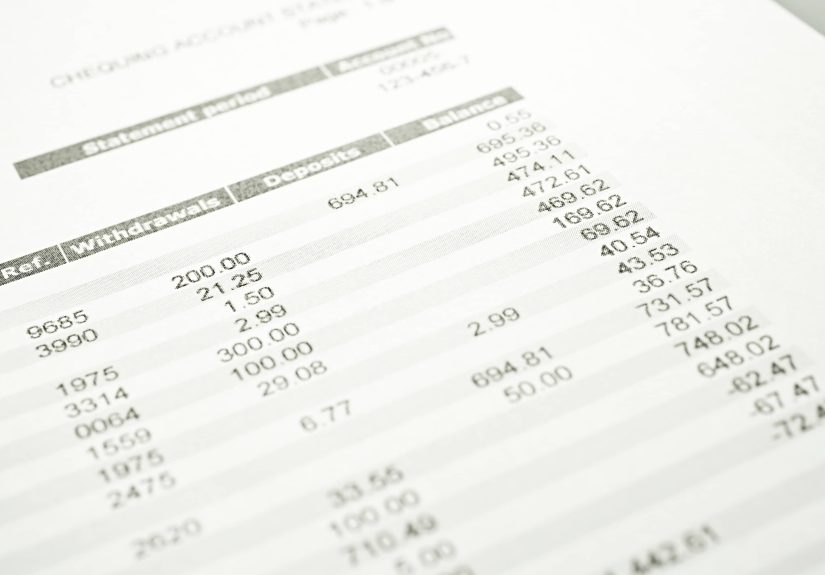

A bank statement is a summary of everything that happened in your checking or savings account during a statement period (often about a month). It shows

your starting balance, ending balance, and the transactions in betweenmoney in, money out, and any fees or interest along the way.

If you’ve ever checked your balance online and thought, “That doesn’t look right,” your statement is the place to solve the mystery. It’s also the

document many lenders and landlords use to verify income, spending patterns, or cash reservesso understanding it helps you not only manage money, but

prove you manage money.

Step 1: Start at the TopThe “Statement Header” Tells You the Rules

The first section (usually the top of page one) is the bank’s “ID card” for the statement. It typically includes:

- Statement period (the exact start and end date of what’s included)

- Account type (checking, savings, money market, etc.)

- Account number (often partially masked for security)

- Customer service contact (useful when something looks off)

Before you look at transactions, check the statement period. If you’re trying to find a purchase from “last Friday,” and last Friday is outside the date

range, you’re hunting in the wrong month. (We’ve all blamed the statement when the calendar was the real villain.)

Step 2: Understand the Account SummaryYour Month in One Snapshot

Most statements include a quick summary that looks something like:

- Beginning balance

- Total deposits/credits

- Total withdrawals/debits

- Service fees

- Ending balance

The “Balance Math” (So You Can Sanity-Check Fast)

A simple way to confirm your statement makes sense is this:

Beginning balance + Deposits/Credits − Withdrawals/Debits − Fees + Interest =

Ending balance

You don’t have to calculate every penny every month, but doing a quick “does this add up?” check can reveal obvious errorslike a missing paycheck, a

duplicated charge, or a fee that shouldn’t be there.

Step 3: Learn the Two Dates That Cause Most Confusion

Many transactions show more than one date (or you may notice the date you bought something doesn’t match the date it appears on your statement). The two

big ones are:

- Transaction date: when you made the purchase/transfer or when it was authorized

- Posting date: when the bank officially processed it and applied it to your account ledger

These can differ by a day or three (sometimes more on weekends/holidays). That doesn’t automatically mean something is wrongit’s often just how payment

systems process transactions.

Pending vs. Posted: The “Available Balance” Trap

Online banking shows an available balance that may include pending card authorizations and holds. Your statement is usually based on

posted transactions during the statement period, and it may not list items that were pending at the time of statement generation.

Translation: your statement might not match what you “remember” seeing in the app on a random Tuesday night at 11:47 PM. Your memory isn’t badyour money

was just in the awkward “pending” phase.

Step 4: Decode the Transaction ListWhere the Story Actually Lives

This is the longest section of most statements, because it lists the line items that change your balance. Each transaction often shows:

- Date

- Description (merchant name, transfer label, or code)

- Amount (money out or money in)

- Running balance (sometimes shown, sometimes not)

Credits vs. Debits (Not the “Credit Card” Kind)

On a bank statement:

- Credit usually means money into your account (paycheck, refund, transfer in)

- Debit usually means money out of your account (purchase, bill payment, transfer out)

Common Statement Descriptions (A Translator Ring for “Bank-Speak”)

Banks don’t always print “You bought tacos.” They print something like “POS DEBIT 1122 TACO PLANET #049.” Here are common terms you may see:

| Statement Term | What It Usually Means | What to Do If You Don’t Recognize It |

|---|---|---|

| POS | Point-of-sale purchase (debit card purchase in-store or online) | Look for a merchant name, location, or receipt email; check your card wallet/app |

| ACH | Automated Clearing House transfer (direct deposit, bill pay, subscriptions, bank-to-bank transfers) | Check if it matches payroll, utilities, rent, memberships, or transfer activity |

| ATM | Cash withdrawal (or sometimes ATM fee) | Verify date/time/location; confirm you withdrew that cash |

| CHK / CHECK | Paper check cleared | Match check number to your records; if unknown, contact the bank quickly |

| XFER / TRANSFER | Transfer between your accounts (or to someone else if you authorized it) | Confirm it matches your own transfers or scheduled moves |

| BILL PAY | Online bill payment you initiated through the bank | Cross-check your bill pay history in online banking |

| INT | Interest paid (usually savings; sometimes interest-bearing checking) | Confirm rate/amount makes sense for your balance |

| FEE / SVC CHG | Service charge (maintenance fee, overdraft, paper statement fee, etc.) | Find the fee description; check how to avoid it next month |

Important: banks and processors don’t use one universal language. The same type of transaction can look different depending on your bank, the payment

network, and the merchant’s setup. If a description looks like alphabet soup, that’s normal. If it looks like alphabet soup and you don’t

recognize the amount or timing, that’s your cue to investigate.

Step 5: Pay Special Attention to FeesThey’re Small Until They’re Not

Fees often hide in plain sight because they look “official,” and your brain may treat them like weather: unavoidable and vaguely annoying. But many bank

fees are preventable once you know where they show up.

Common Fees You’ll See on Statements

- Monthly maintenance fee (often waived with direct deposit, minimum balance, or certain account types)

- Overdraft fee (you spent more than available funds and the bank covered it)

- NSF/returned item fee (a payment bounced because funds weren’t available)

- ATM fees (out-of-network usage, plus possible operator fees)

- Paper statement fee (some accounts charge for mailed statements)

- Wire/transfer fees (depends on your bank and transfer type)

How to Use Your Statement to Reduce Fees Next Month

When you spot a fee, ask two questions:

- What triggered it? (Low balance? Too many withdrawals? Out-of-network ATM?)

- What rule would have avoided it? (Maintain a buffer? Switch accounts? Turn on alerts?)

Your statement is like a “receipt” for your bank relationship. If you’re paying for features you don’t useor getting hit with fees you didn’t

anticipateit may be time to change the way you bank, not just the way you budget.

Step 6: Understand ACH, Direct Deposit, and Auto-Pay (Because They Run Your Life)

A huge portion of modern banking runs through ACH transfersthink payroll direct deposit, government benefits, mortgage payments, utility

auto-pay, subscription bills, and bank-to-bank transfers.

On statements, ACH entries can be labeled as:

- ACH Credit: money pushed into your account (like a paycheck)

- ACH Debit: money pulled from your account (like an auto-pay bill)

Why ACH Descriptions Can Look Weird

ACH entries often reflect the “originator” name from the sending systemnot the brand name you remember. For example, your streaming service might show up

as a parent company or billing processor. If you don’t recognize it, search your email for receipts and check your subscription settings. You may discover

a forgotten trial that turned into a paid planaka the classic “I swear I canceled that” phenomenon.

Step 7: Reconcile Your Statement in 10–15 Minutes (Yes, Really)

Reconciling just means comparing your statement to your own records to confirm everything is legitimate and accounted for. You can do this with a budgeting

app, a spreadsheet, or the ancient art of “reading carefully while holding coffee.”

A Simple Personal Reconciliation Checklist

- Confirm the beginning balance matches last statement’s ending balance.

- Match deposits (paychecks, transfers, refunds) to what you expected.

- Scan withdrawals and mark anything unfamiliar.

- Look for fees and note how to avoid them.

- Check the ending balance using the “balance math” from earlier.

- List outstanding items (checks you wrote that haven’t cleared, pending refunds, holds).

If you’ve never done this before, your first reconciliation might take 30 minutes. After that, it’s usually quickbecause you’ll know what “normal” looks

like for your account. And once you know normal, weird stuff stands out immediately.

Step 8: How to Spot Errors and Fraud Using Your Statement

Statements are one of the best tools for catching problems early. Here are red flags worth circling (mentally or literally):

- Duplicate charges (same amount, same merchant, same daytwice)

- Small “test” transactions you don’t recognize (fraudsters sometimes probe before bigger attempts)

- Unexpected fees (especially maintenance or overdraft fees you didn’t expect)

- Transfers you didn’t initiate (especially if labeled as external)

- Checks you didn’t write or check numbers that don’t match your records

- Refunds that never showed up (or show up for the wrong amount)

What to Do Immediately If Something Looks Wrong

- Contact your bank fast using the number on your statement or official website/app.

- Identify the transaction: date, amount, and description.

- Ask about dispute/error steps (banks have specific processes and deadlines).

- Secure your account: change passwords, enable alerts, and consider freezing/replacing a compromised card.

- Document everything: who you spoke to, when, and what they said.

The “boring” reason to review statements monthly is exactly this: many consumer protections depend on you reporting suspicious electronic transactions

within specific time windows. In practice, the sooner you report, the easier it is to investigate and resolve.

Step 9: Make Your Statement Work for You (Budgeting, Goals, and “Subscription Creep”)

Even if you’re not a budgeting person, your statement can function like a monthly financial checkup. Try these quick scans:

1) The “Recurring Charges” Sweep

Look for repeating items: streaming services, apps, gym memberships, software, donation subscriptions, and “free trials” that quietly graduated into paid

adulthood. If you see something you don’t use, cancel it and give yourself a monthly raise.

2) The “Fees and Interest” Audit

Add up fees for the month. Even “just” $10–$15 is real money. If fees are recurring, you have options: change account type, meet waiver requirements,

move to a bank/credit union with fewer fees, or adjust habits (like keeping a small buffer).

3) The “Reality Check” Categories

Pick three categories that tend to balloonfood delivery, online shopping, rideshare, convenience storesand estimate totals by scanning the transaction

list. You don’t need perfection. You need awareness. Awareness is what makes “small changes” actually happen.

Step 10: Know What to Save (and What to Shred)

Statements are useful records, but you don’t need to hoard paper like it’s a limited-edition collectible.

Practical retention guidelines many people use

- Monthly statements: keep until you’ve reconciled and confirmed everything is correct.

- Proof for major purchases: keep statements showing large transactions for warranties, reimbursements, or disputes.

- Tax-related items: if your statement supports tax deductions, income, or business expenses, keep it with your tax records.

- Loan/lease applications: keep recent statements you used to apply until the process is complete.

If you keep statements digitally, protect them. Bank statements are packed with sensitive information. Use strong passwords, enable multi-factor

authentication, and store PDFs in a secure location (not “Downloads,” where mystery files go to party).

Step 11: A Quick “Statement Confidence” Routine You Can Repeat Monthly

If you want a simple habit that takes less time than scrolling social media, try this monthly routine:

- Read the summary (beginning balance, ending balance, fees).

- Search for fees (circle themmentally or with a highlighter).

- Scan for unfamiliar transactions (anything you can’t explain gets investigated).

- Check recurring charges (cancel what you don’t use).

- File it securely (or shred paper statements immediately).

You don’t need to become a human calculator. You just need to become a person who notices what’s happening. That’s how you keep your money from wandering

off like a toddler in a toy aisle.

Real-World Experiences: The Statement Mysteries People Actually Run Into (Extra )

Reading a bank statement gets a lot easier once you’ve lived through a few classic “what is that?” moments. Below are common real-life scenarios

people run intoplus what their statements taught them. Think of these as financial campfire stories, except the monster is usually a fee.

1) The Gas Station Charge That Looks Wrong (But Isn’t… Yet)

Someone buys gas for about $42. The next day, their online banking shows a much larger number temporarily tied to that purchase. Panic ensues. The

statement lesson: card purchases can start as an authorization/hold and later “settle” for the final amount. If you only look at the app mid-process, it

can look like you paid for the entire gas station. When the statement arrives, the posted transaction is typically the true final amount. The move here is

to watch for the posted amount and check whether the hold drops off.

2) The Merchant Name That Sounds Like a Sci-Fi Villain

A person sees “ACH DEBIT VENDSYS-3921” and assumes their account got hacked by robots. In reality, it’s their perfectly normal subscriptionjust billed by

a payment processor instead of the brand name they recognize. The statement lesson: merchant descriptors don’t always match the logo you remember. When

something is unclear, the fastest detective work is searching your email for receipts and checking subscription lists in your app stores and streaming

services.

3) The “I Didn’t Overdraft” Overdraft

Someone checks their balance, sees $120, then makes a $25 purchase. Later: overdraft fee. Cue outrage. The statement lesson: timing matters. A pending

bill payment, a check that cleared, or a transaction that posted later can change the order of what actually hits the account. That’s why statement review

is valuableit reveals the sequence of posted transactions and the fees tied to them. The fix is usually practical: add a buffer, turn on low-balance

alerts, and avoid skating too close to zero.

4) The Missing Paycheck That Wasn’t Missing

A paycheck doesn’t show up on payday morning. The person refreshes their app like it’s a sports score. Later that dayor the next business dayit appears.

The statement lesson: direct deposits often run through ACH processing schedules, and holidays/weekends can shift posting. When the statement arrives, it

clarifies the actual posting date and confirms whether it was truly delayed or just not yet posted.

5) The Refund That Took Forever

Someone returns a purchase and expects the refund instantly because they’ve been spoiled by modern shipping. But refunds can take several business days,

and sometimes they appear as a different descriptor than the original purchase. The statement lesson: track refunds by amount and approximate date, not

just merchant name. When in doubt, compare the original charge and look for a credit entry later in the period (or the next one).

6) The Duplicate Charge That Was Actually Two Transactions

Two charges appear for the same restaurant, same amount, same day. Fraud? Maybe. Or… it’s dinner and a separate tip adjustment that processed later.

The statement lesson: compare posted transactions and look for clues like “adjusted” amounts or a separate “gratuity” entry. If it still doesn’t make

sense, dispute itbecause “maybe it’s fine” is not a fraud strategy.

7) The Tiny Charge That Saved Them from a Big One

A person notices a $1.27 transaction they don’t recognize. It would be easy to ignoreuntil they remember that small charges can be test transactions.

They call the bank, replace the card, and avoid what could have become a larger problem. The statement lesson: small weirdness is still weirdness. Your

statement isn’t just historyit’s an early warning system.

The big takeaway from these experiences is simple: once you know how statements are structuredwhat’s a fee, what’s a posted transaction, what’s a hold,

and what “ACH” typically meansyou stop reacting emotionally to every unfamiliar abbreviation and start reacting intelligently. That’s the real upgrade:

confidence. And confidence is a lot cheaper than overdraft fees.

Conclusion

Reading your bank statement is less about being “good at money” and more about being aware of money. The statement shows you what happened, how it

happened, and what it cost youespecially in fees. Once you know where to look, you can catch errors, cut waste, avoid surprise charges, and spot fraud

faster. Ten minutes a month can protect hundreds of dollars a year. That’s a pretty good hourly rate.