Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- The Moment That Made the Internet Go Quiet

- Why the “Black Summer” Bushfires Hit So Hard

- Australia Zoo, the Irwin Family, and a Front-Row Seat to Disaster

- What the Bushfires Taught the World (Including the U.S.)

- How to Help Without Falling for “Clicktivism”

- Why This Story Still Matters in 2026

- Conclusion: Tears, Truth, and What We Do Next

- Experiences Related to This Moment: What People Remember (And Why It Sticks)

- SEO Tags

Every once in a while, a clip cuts through the internet’s usual noiseno hot takes, no ironic captions, no “wait for it.”

Just a human being trying to stay composed while talking about something that hurts.

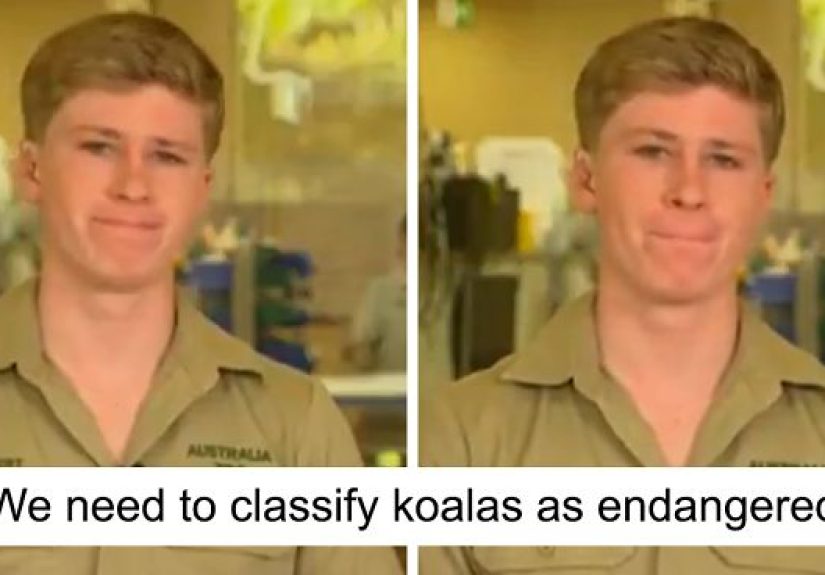

That’s what happened when Robert Irwinwildlife conservationist, Australia Zoo’s most recognizable khaki-clad torchbearer, and Steve Irwin’s sonvisibly fought back tears during a TV interview about the Australian bushfires and what they did to wildlife.

It wasn’t a “viral moment” in the goofy, algorithm-fed sense. It was a pause. A crack in the armor. A reminder that behind every headline about acres burned and smoke maps is a long line of living creatures who didn’t ask to become statistics.

This article breaks down what Robert Irwin said, why it resonated so widely, what the “Black Summer” bushfires revealed about wildlife rescue and recovery, and what lessons still matter nowbecause Australia’s fire story didn’t end when the cameras moved on.

The Moment That Made the Internet Go Quiet

In early January 2020, Robert and his mom, Terri Irwin, appeared in an interview (widely reported as being on Australia’s Sunrise) to talk about the bushfire emergency and the wave of injured wildlife arriving for care.

As they described what was happeningespecially to koalas and other native animalsRobert grew emotional and had to work to keep his voice steady.

It wasn’t performative. If anything, it looked like the opposite: someone doing the hard thing (speaking publicly) while wishing they didn’t have to.

Media coverage at the time emphasized two points:

Robert’s heartbreak came from what they were seeing up close, and the Irwins were using their platform to push attention toward wildlife rescue, not themselves.

In other words, the tears weren’t the headlinewhat the tears pointed to was.

Why the “Black Summer” Bushfires Hit So Hard

A season that wasn’t “just another bad summer”

Australia is no stranger to bushfires. Fire is part of many Australian ecosystems, and Indigenous land management practices have included cultural burning for thousands of years.

But the 2019–2020 seasonoften called “Black Summer”became a global reference point for scale, duration, and cascading impacts.

The most commonly cited summaries describe a disaster that stretched across months, burned vast areas, destroyed thousands of structures, and blanketed cities in dangerous smoke.

It wasn’t only the flames. It was the atmospherethick, persistent haze that turned daylight into a sepia filter no one wanted, and air quality into a public-health problem.

Scientists also tracked effects far beyond Australia’s borders: massive smoke plumes that rose to unusual heights, traveled long distances, and influenced atmospheric conditions.

In plain English: this was not a local campfire situation. This was “the planet noticed” territory.

Wildlife: the headline is koalas, the story is everything

Koalas became the global symbolpartly because they’re iconic, and partly because eucalyptus forests and koalas are closely tied, so habitat loss hits them hard.

But the wildlife story was always bigger than one species.

One widely publicized estimate (reported in scientific and major-media coverage) suggested up to billions of animals were killed, injured, or displaced during Black Summer.

Even when you treat those numbers carefullyas estimates, not a perfect headcountthe core truth doesn’t change: the ecological shock was enormous.

And the suffering didn’t stop when flames passed through.

Animals that survived could face a brutal “after”:

- Habitat loss (no shelter, fewer nesting sites, less canopy cover)

- Food and water shortages in scorched landscapes

- Higher risk from cars and pets as animals moved into unfamiliar or human-dominated spaces

- Predation pressure because the landscape offers fewer hiding places

This is part of what made Robert Irwin’s emotion so relatable: it wasn’t just grief about what already happenedit was grief about what was still unfolding.

The “knock-on effects” can last far longer than the news cycle.

Australia Zoo, the Irwin Family, and a Front-Row Seat to Disaster

From TV heroes to triage reality

The Irwins aren’t just wildlife personalities; their work is tied to a real clinical pipeline through the Australia Zoo Wildlife Hospital and partner rescue networks.

During the bushfire crisis, reporting highlighted the hospital’s rising caseload and the need for facilities, supplies, and trained hands to treat wildlife at scale.

Headlines at the time noted milestones like the hospital treating its 90,000th patientan attention-grabbing number that also quietly communicates the reality:

wildlife hospitals don’t exist for “cute content.” They exist because animals get injured, sick, displaced, and sometimes caught in human-made emergencies.

Bushfires supercharge all of that in a matter of days.

When Terri and Robert spoke publicly, they weren’t describing an abstract tragedy from a distance.

They were describing what comes through the dooranimals that need hydration, pain relief, wound care, antibiotics, respiratory support, and time.

In a disaster, time is the cruel currency nobody has enough of.

Why his tears mattered (and why that’s not “soft”)

In crisis messaging, people sometimes mistake emotion for weakness.

But in conservationespecially wildlife rescueemotion is often evidence of proximity.

If you feel nothing while describing mass habitat loss, you might be too far away from the problem… or too practiced at looking away.

Robert Irwin’s reaction also cut through a common modern problem: compassion fatigue.

We scroll past disasters because there are always more disasters.

A young conservationist visibly struggling to keep it together on live TV is a reminder that the stakes are not theoretical.

And yesthere’s a practical angle here.

Authentic public emotion can:

- Increase attention to underfunded rescue work

- Boost donations to legitimate organizations

- Encourage volunteer sign-ups and supply drives

- Keep the conversation alive after the “breaking news” banner disappears

The key word is legitimate.

Emotion opens wallets; wisdom should guide where the money goes.

What the Bushfires Taught the World (Including the U.S.)

Smoke doesn’t need a passport

One of the most striking scientific storylines from Black Summer involved smoke behavior.

NASA and NOAA coverage described smoke plumes reaching unusual heights, traveling long distances, and creating measurable atmospheric effects.

Some research even linked smoke-related aerosol deposition to changes in ocean conditions and phytoplankton blooms.

If you’re in the U.S., this probably sounds uncomfortably familiarbecause wildfire smoke has become a recurring reality across North America, too.

The lesson is simple and unsettling: fire is not only a “burn zone” issue.

Smoke turns fire into a regional (and sometimes global) event.

The health angle: beyond coughing

Broadly speaking, wildfire smoke can affect more than just lungsespecially for people with asthma, COPD, heart disease, older adults, young children, and pregnant people.

Public-health reporting during the Australian crisis emphasized how heavy smoke exposure can raise health risks over days and weeks, not just hours.

The psychological health impact matters too.

Disasters don’t only burn trees; they burn routines.

Communities deal with evacuation stress, loss, displacement, and uncertaintyplus the emotional shock of seeing familiar landscapes transformed.

Climate ingredients: heat, drought, wind, and a warming baseline

When people ask, “Was climate change involved?” the honest answer is rarely a clean yes/no.

Fire seasons are shaped by multiple factors: rainfall patterns, fuel loads, drought conditions, heatwaves, humidity, winds, and ignition sources.

But scientific and mainstream reporting around Black Summer consistently highlighted that hotter conditions and long-term dryness increase the likelihood of extreme fire weather.

A warming baseline can load the dicemaking severe fire seasons more probable and, in some cases, more intense.

Think of it like this: climate doesn’t always “start” the fire, but it can help build the conditions that let a fire spread faster, burn hotter, and last longer.

That’s not politics. That’s physics with terrible timing.

How to Help Without Falling for “Clicktivism”

When a clip like Robert Irwin’s interview circulates, the emotional instinct is to do something.

Good. Keep that instinct. Just pair it with a little strategy.

1) Support organizations doing verified rescue and recovery work

Wildlife hospitals, rescue units, habitat restoration groups, and emergency-relief organizations often need:

funds (to buy supplies and expand capacity), transport vehicles, medical equipment, and trained staff.

If you donate, prioritize organizations with transparency: clear mission, public reporting, and track record.

2) Share carefullymisinformation spreads fast in disasters

During Black Summer, viral stories about animal “heroes” and miracle behaviors spread quicklysome were exaggerated or misunderstood.

Feel-good misinformation can still be misinformation, and it can pull attention away from what animals actually need: habitat, water, veterinary care, and time.

3) Think long-term: recovery takes years, not weeks

Post-fire landscapes can recover, but the process is uneven.

Some habitats rebound faster than others.

Animals that rely on old-growth featurestree hollows, complex understory, stable food websdon’t get those back overnight.

Long-term support can look like:

- Funding habitat restoration and invasive predator management

- Supporting research and monitoring of vulnerable species

- Backing community preparedness and smoke-health education

- Helping wildlife hospitals expand capacity before the next crisis

Why This Story Still Matters in 2026

It’s tempting to treat Black Summer as a historical chapter: “That was intense. Glad it’s over.”

But fire risk is an ongoing reality.

In January 2026, major news organizations reported severe bushfires again affecting parts of southeastern Australia.

The details differ, but the theme is familiar: extreme heat, fast-moving fire conditions, evacuations, infrastructure losses.

That context changes how we should interpret Robert Irwin’s tears.

They weren’t only about one season.

They were about a patternand about the urgency of building systems that protect wildlife, people, and ecosystems before disaster hits.

Conclusion: Tears, Truth, and What We Do Next

Robert Irwin struggling to hold back tears wasn’t celebrity drama.

It was an honest reaction to the reality of wildlife conservation in a warming, fire-prone world.

It reminded people that bushfires aren’t just “nature doing nature things.”

They’re emergencies with medical consequences, ecological consequences, and human consequencesoften all at once.

If the clip moved you, that’s not something to be embarrassed about.

Empathy is a feature, not a bug.

The goal is to turn that empathy into smart action:

support credible rescue work, resist misinformation, and think long-term about recovery and prevention.

Because the most important part of the story isn’t that Robert Irwin nearly cried on TV.

It’s why he nearly criedand what we choose to do with the truth he was trying to say out loud.

Experiences Related to This Moment: What People Remember (And Why It Sticks)

If you were online in early 2020, you might remember how the bushfire coverage felt: relentless, surreal, and oddly personal even if you lived thousands of miles away.

Many people describe the same first reactionseeing the footage and thinking, “This can’t be real.”

Not because fires are new, but because the scale looked like something out of a dystopian movie… except the cast was real wildlife, real towns, and real responders.

For a lot of viewers, Robert Irwin’s interview became the emotional “translation layer.”

Numbers like “millions of hectares” and “smoke in the stratosphere” are hard to hold in your head.

But watching a young conservationist pause, breathe, and fight the tremble in his voicethat’s easy to understand.

You don’t need a degree in ecology to recognize grief.

People who work in caregiving fieldsnurses, vets, animal shelter staff, social workersoften say the hardest part of a crisis is the moment you realize the need is bigger than your capacity.

That feeling showed up in bushfire stories again and again: wildlife carers trying to triage nonstop; volunteers organizing supplies; communities improvising recovery plans while still dealing with smoke and uncertainty.

Even from a distance, you could sense the exhaustion: not dramatic exhaustion, but the quiet kind where you keep moving because stopping would mean feeling everything at once.

Some experiences were small but unforgettable.

Viewers remember checking updates first thing in the morning and last thing at night, like the news had become a weather app for catastrophe.

People remember donating to wildlife hospitals or sharing fundraisersthen Googling “Is this legit?” because disasters attract scams like porch lights attract moths.

Teachers and parents recall kids asking, “Are the koalas okay?”a question both heartbreaking and hopeful, because it assumes “okay” is still possible.

There’s also the experience of smoke itself, described by many as disorienting: the strange light, the smell that seeps into clothes, the sense that you’re living inside a warning.

Even for those outside Australia, wildfire smoke has a way of making climate risk feel immediatebecause you can taste it.

It turns the abstract into the physical.

And then there’s the long-tail experiencethe part that happens after the headlines move on.

Recovery stories are quieter: habitat restoration, careful monitoring, rebuilding facilities, fundraising for the unglamorous basics (feed, enclosures, transport, medical gear).

That’s why the Irwins’ messaging mattered: it pointed attention toward the unphotogenic work that saves animals one patient at a time.

If you take one “experience lesson” from the whole thing, it might be this:

emotions don’t have to be the end of the story.

They can be the beginningthe moment you decide to care with your brain and your heart.

That’s what Robert Irwin’s tears offered the world: not despair, but a signal flare saying, “This is real. Please don’t look away.”