Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What CAPE Is and Why Investors Respect It

- The “CAPE Fear” Thesis: Why Lower Returns Feel Plausible

- What CAPE Gets Rightand Where It Can Mislead

- So… Should You Be Afraid?

- A Practical Playbook for a High-CAPE World

- Scenario Thinking: Three Ways CAPE Fear Can Play Out

- 500-Word Experience Section: Investor Stories from CAPE Anxiety

- Experience 1: The “I’ll Wait for a Better Entry” Investor

- Experience 2: The “All U.S., All Growth, All the Time” Portfolio

- Experience 3: The Retiree Who Feared Sequence Risk More Than Headlines

- Experience 4: The Young Investor Who Used CAPE Correctly

- Experience 5: The Committee That Replaced Forecast Pride with Risk Budgeting

- Conclusion

If you invest long enough, you eventually meet CAPEthe Cyclically Adjusted Price-to-Earnings ratioand CAPE eventually tries to ruin your mood.

You check it once, see it running hot, and suddenly your retirement spreadsheet starts looking like a suspense movie.

The core fear is simple: when valuations are high, future returns are often lower. Not always. Not immediately. But often enough to make investors sweat.

Today’s market context makes that fear louder. U.S. equities have spent years being expensive versus history, with the Shiller CAPE ratio around levels

that have historically been rare. At the same time, earnings growth, AI optimism, and concentrated mega-cap leadership have kept prices elevated.

So which story wins: valuation gravity or structural change?

In this deep dive, we’ll break down what CAPE really tells you, what it absolutely does not tell you, and how to build a practical plan

when “lower expected returns” becomes the headline in your head. No doom scroll required. Just clear thinking, realistic assumptions, and a portfolio

that can survive both bubble chatter and boring decades.

What CAPE Is and Why Investors Respect It

CAPE in plain English

CAPE compares stock prices to average inflation-adjusted earnings over the last 10 years. That 10-year smoothing is the whole point: it filters out

one-off booms and recessions so you get a more stable valuation signal than a standard one-year P/E.

In other words, CAPE is less “what happened last quarter” and more “what price are we paying for a full business cycle of profits?”

Why people care so much about it

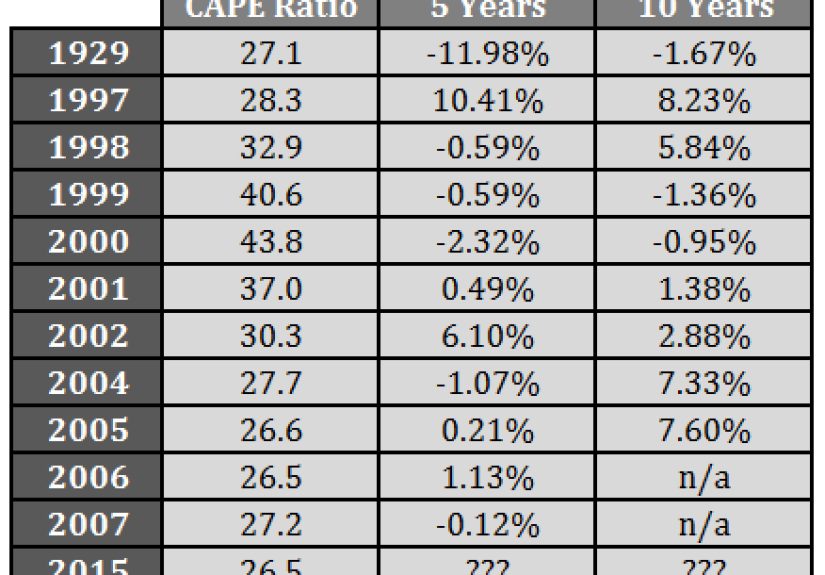

Over long horizons, starting valuation has had a meaningful relationship with future returns. When investors buy at rich multiples, later returns

tend to be lower; when they buy at lower multiples, later returns tend to be higher. That does not mean CAPE is a short-term timing tool.

It’s better viewed as a long-range weather forecast than a day-trading signal.

Historically, the CAPE long-run average is near the high teens, while recent readings have sat far above that range. If CAPE is elevated, the market

may still rise next month, next quarter, or even for years. But elevated valuation often compresses the long-term return runway unless earnings growth

stays extraordinary for a long time.

The “CAPE Fear” Thesis: Why Lower Returns Feel Plausible

Valuation math is stubborn

Returns come from three broad engines: earnings growth, dividends/buybacks, and changes in valuation multiples.

If you begin with a high multiple, you’re asking future investors to pay an even higher multiple (hard), or you’re assuming earnings growth carries

most of the burden (possible, but demanding). This is why many capital market outlooks now project more modest U.S. equity returns over the next decade.

Major institutions are signaling caution

Several large U.S.-focused research houses now describe U.S. long-term equity returns as muted relative to recent history.

You’ll see different models and exact numbers, but the broad message is consistent: high starting valuations make long-run outcomes less forgiving.

Even when near-term momentum remains strong, expected returns over 5–10 years often look lower than what investors got used to in the 2010s.

Concentration risk makes valuation nerves worse

Market leadership has become narrow, with mega-cap technology and AI-related names dominating index behavior.

Concentration itself isn’t automatically badleaders can keep leadingbut it increases fragility if expectations slip.

When many hopes sit in a few companies, valuation disappointment can travel fast.

What CAPE Gets Rightand Where It Can Mislead

CAPE is strongest at long horizons, weakest at short horizons

CAPE has more explanatory power over long horizons (like 10 years) than over one-year windows. So yes, it matters for long-term planning.

No, it does not tell you what the market will do next quarter. Investors get into trouble when they turn a strategic metric into a tactical trigger.

High CAPE does not equal immediate crash

Markets can stay expensive for a long time, especially during periods of strong productivity growth, falling rates, or major technological shifts.

High CAPE can coexist with strong returns for years before valuation pressure shows up. That lag is exactly why “all-in/all-out” calls based solely on CAPE

often fail in real life.

Macro shocks matter as much as valuation

Some research notes that weak long-term outcomes after high CAPE starting points were often associated with major crises (war, inflation shocks,

deep recessions, systemic financial stress). Translation: valuation sets the stage, but macro events write part of the script.

CAPE is important, but it does not operate in a vacuum.

Accounting, margins, and index composition have changed

Modern indexes include business models with large intangible assets, platform economics, and global scale effects that differ from earlier decades.

Comparing today’s CAPE to 1960 without context can be misleading. The ratio still matters, but “fair value” may not be a single fixed number forever.

Think range, not magic threshold.

So… Should You Be Afraid?

Be concerned, not paralyzed.

CAPE fear is rational if it means you lower return expectations, diversify more thoughtfully, and improve risk control.

CAPE fear becomes harmful when it pushes you into emotional timing, endless cash hoarding, or abandoning a long-term plan every time the market rallies.

The better question is not “Will CAPE be right tomorrow?”

The better question is “If future returns are lower than the last decade, is my plan still robust?”

That framing moves you from prediction theater to portfolio engineering.

A Practical Playbook for a High-CAPE World

1) Reset expected returns

If your plan assumes double-digit U.S. equity returns forever, update it.

Use a realistic range and run multiple scenarios (good, base, bad). Lower expected returns now means fewer unpleasant surprises later.

2) Broaden diversification on purpose

When one region is expensive, global diversification becomes more than textbook adviceit becomes valuation management.

Non-U.S. developed and emerging markets may offer different starting points and currency dynamics.

Diversification won’t win every year, but it can improve the odds of a smoother decade.

3) Respect fixed income again

In a lower-equity-return environment, bonds and high-quality fixed income can matter more than they did during zero-rate years.

They provide yield, diversification potential, and rebalancing ammunition when equities stumble.

“Boring” may be beautiful if expected equity premiums compress.

4) Rebalance instead of react

Build predetermined rebalancing rules (calendar-based or threshold-based).

That lets you sell a little of what got expensive and buy what laggedwithout pretending you can nail tops and bottoms.

Rebalancing is disciplined humility, and humility is an underrated alpha source.

5) Focus on savings rate and costs

In lower-return regimes, controllable variables become king: contribution rate, fees, taxes, and behavior.

You cannot force the market to deliver 12%, but you can avoid paying 2% for mediocre complexity and panic-selling at the worst possible time.

Scenario Thinking: Three Ways CAPE Fear Can Play Out

Scenario A: “Soft landing, slow grind”

Earnings keep growing, valuations fade slowly, and returns come in below the last decade but still positive.

This is the quiet outcome many investors underestimate because it lacks drama.

Scenario B: “Productivity surprise”

AI and capital spending deliver stronger productivity gains than expected. Earnings growth outpaces valuation drag.

CAPE remains elevated longer, and skeptics look early (again).

Scenario C: “Shock + repricing”

Growth disappoints, policy risk rises, or financial conditions tighten quickly. High multiples compress fast.

Returns recover eventually, but the path includes a painful drawdown that punishes concentrated portfolios.

Good plans survive all three. Great plans are intentionally built for all three.

500-Word Experience Section: Investor Stories from CAPE Anxiety

Experience 1: The “I’ll Wait for a Better Entry” Investor

Daniel, 34, read three valuation reports in one weekend and decided the market was “too expensive to touch.” He moved fresh savings to cash

and promised to buy back in after “a meaningful correction.” The correction never arrived on his schedule.

Twelve months later, the index was higher, his cash earned something but not enough, and he felt trapped by his own rule.

His real pain wasn’t missing one rally; it was losing trust in any decision framework. Every up day felt like regret, every down day felt like vindication.

Eventually, he switched to phased monthly investing. That did two things: it lowered emotional pressure and restored process discipline.

CAPE still informed his expectations, but it no longer decided his entire behavior. His takeaway: valuation is a thermostat, not an on/off switch.

Experience 2: The “All U.S., All Growth, All the Time” Portfolio

Priya, 41, had a portfolio that looked brilliant in bull markets: heavy U.S. large-cap growth, minimal bonds, almost no international exposure.

She wasn’t recklessjust optimized for what had worked recently. Then a sharp volatility episode hit the exact names she owned most.

Her portfolio dropped faster than the broad market, and she discovered that concentration risk feels theoretical until it isn’t.

She didn’t abandon equities; she redesigned them. She kept U.S. exposure, added international equities, layered in high-quality bonds, and wrote

a rebalancing rule she could follow during stressful weeks. The portfolio now grows a little slower in euphoric phases but feels much sturdier.

Her lesson: in expensive markets, resilience often beats precision.

Experience 3: The Retiree Who Feared Sequence Risk More Than Headlines

Mark and Ellen entered retirement with a common fear: “What if our first five years are bad?” CAPE headlines amplified that anxiety.

Instead of chasing a market call, they worked backward from spending needs. They built a “safety bucket” of short-term bonds and cash for near-term

withdrawals, a mid-term bond sleeve, and a diversified equity sleeve for longer horizons.

They also adjusted withdrawal flexibilityspending a bit less after weak years and a bit more after strong years.

CAPE informed their expected return assumptions, which helped them set conservative withdrawal rules, but it did not force a panic de-risking move.

Their breakthrough was emotional as much as financial: they stopped asking, “Will the market crash?” and started asking, “Can our plan handle one?”

Experience 4: The Young Investor Who Used CAPE Correctly

Mia, 27, heard that high CAPE meant low future returns and worried she had started investing at the “worst possible time.”

After a few conversations with an advisor, she reframed the issue.

A high CAPE environment might lower expected returns, but she had three structural advantages: long horizon, regular contributions,

and high human-capital growth from her career. She increased her automatic contribution rate by 2%, kept costs low with broad index funds,

and ignored prediction content for a while.

Ironically, accepting “maybe lower returns” improved her behavior. She saved more, traded less, and stuck to her allocation.

Her practical insight: when expected returns are lower, contribution discipline matters even more.

Experience 5: The Committee That Replaced Forecast Pride with Risk Budgeting

A small family office investment committee used to debate one question every quarter: “Are we bullish or bearish?” The result was constant

tactical tinkering and no shared framework. After several whipsaw trades, they adopted a different model.

CAPE and valuation metrics became one input in a broader dashboard that included earnings breadth, credit conditions, inflation regime,

and liquidity signals. Instead of binary calls, they used risk ranges: how much equity risk is acceptable under each regime?

Decision quality improved immediately. Disagreements became about probabilities and sizing, not ego and headlines.

They still made mistakes, but smaller ones. Their cultural shift was simple: forecast less, prepare more.

In high-CAPE environments, that mindset is often the difference between surviving volatility and becoming part of it.

Conclusion

CAPE fear is not irrationalit’s a useful warning label. High valuations often imply lower long-term returns, but they do not provide a countdown clock

for the next correction. The smartest response is not panic or bravado. It is plan design: realistic assumptions, diversified exposures, disciplined

rebalancing, and strong behavior under stress.

If CAPE is elevated, your mission is clear: make your portfolio less dependent on perfect conditions.

Because markets don’t reward perfect predictions nearly as much as they reward durable process.