Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Biodegradable Waste Recycling in Plain English

- Step Zero: Know What “Biodegradable” Really Means

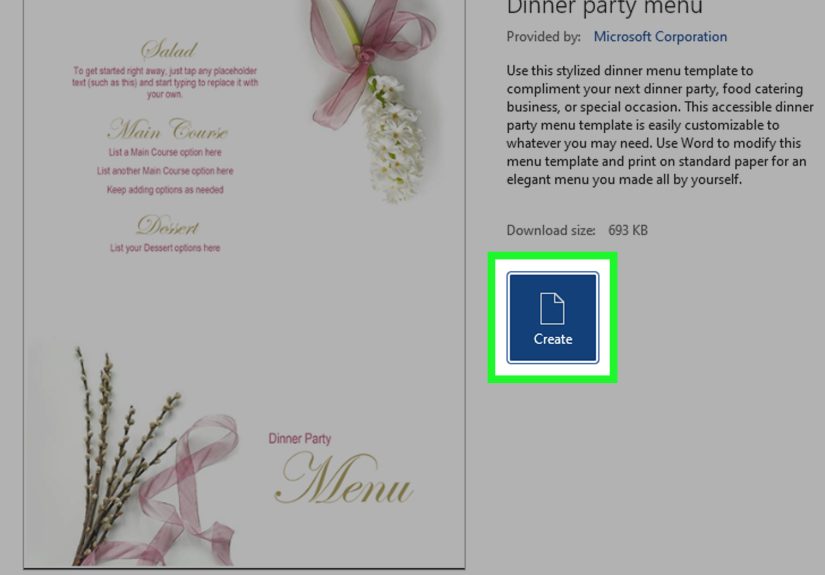

- Before You Start: Pick Your Best Recycling Route

- How to Recycle Biodegradable Waste: 15 Steps

- 1) Separate biodegradable waste at the source

- 2) Learn the “greens vs. browns” rule (your compost’s favorite playlist)

- 3) Choose your system: pile, bin, tumbler, worms, bokashi, or curbside

- 4) Put your compost in the right location (or your future self will resent you)

- 5) Start with a “brown base layer”

- 6) Collect food scraps smartly (and with minimal stink)

- 7) Chop or tear larger pieces to speed things up

- 8) Layer greens and browns like you’re making lasagna (but for dirt)

- 9) Keep moisture at “wrung-out sponge” level

- 10) Add oxygen: turn, mix, or aerate regularly

- 11) Know what NOT to compost (especially at home)

- 12) Handle “compostable” and “biodegradable” packaging carefully

- 13) Troubleshoot fast: smell, pests, and slow breakdown

- 14) Let it cure: finished compost needs a “rest period”

- 15) Use your compost like a pro (and avoid rookie mistakes)

- Bonus: Three “Recycling” Paths People Forget

- Common Myths (That Make Composting Harder Than It Needs to Be)

- Real-World Experiences: What It’s Actually Like ()

- Conclusion: Keep It Simple, Keep It Going

“Biodegradable waste” sounds like something you’d file under Problems for Future Me. But recycling it (mostly by composting) is one of the rare

life upgrades that’s cheap, practical, and weirdly satisfying. You take banana peels, coffee grounds, and sad lettucethen a few weeks later you’ve got

dark, crumbly compost that makes plants look like they hired a personal trainer.

This guide walks you through 15 clear steps to recycle biodegradable waste at home or through local organics programswithout turning your

kitchen into a science experiment that smells like regret. Expect real-world tips, quick fixes for common mistakes, and a little humor (because compost

has enough seriousness already).

Biodegradable Waste Recycling in Plain English

In most U.S. cities, “recycling biodegradable waste” means diverting organic materials from the trash and sending them to a process that

turns them into something usefulusually compost. That can happen through:

- Home composting (backyard pile/bin, tumbler, or trench composting)

- Vermicomposting (worms, a.k.a. nature’s tiny recycling crew)

- Bokashi (fermentation for food scraps, great for small spaces)

- Curbside organics or drop-off programs (your city does the heavy lifting)

Step Zero: Know What “Biodegradable” Really Means

Most kitchen scraps and yard waste are truly compostable in normal conditions. But here’s the plot twist:

“Biodegradable” packaging is not automatically compostable. Some items only break down under specific industrial conditions, and some

never fully break down the way you’d want in compost. Translation: if you toss random “biodegradable” forks into your backyard bin, your future compost

may come with surprise confetti (microplastics are not festive).

Before You Start: Pick Your Best Recycling Route

If you have a yard

A basic bin or pile is the easiest and cheapest path. You can compost food scraps plus leaves and yard trimmings, and you’ll get finished compost for

gardens and landscaping.

If you live in an apartment or condo

Choose one:

curbside organics (if your city offers it), a drop-off site, worm composting indoors, or

bokashi fermentation under the sink. Apartment composting isn’t a mythit’s just a workflow.

If your city has an organics program

Use it. Municipal composting can accept a wider variety of food scraps and paper products than many backyard setups, but rules varyalways follow local

“accepted items” lists so the whole program doesn’t get ruined by one rogue plastic bag.

How to Recycle Biodegradable Waste: 15 Steps

1) Separate biodegradable waste at the source

Set up a simple “organics lane” in your kitchen: a small countertop container for food scraps and a separate spot for yard waste (if you have it).

The goal is to make the right choice the easy choicebecause willpower is not a renewable resource.

2) Learn the “greens vs. browns” rule (your compost’s favorite playlist)

Compost needs two broad ingredient types:

Greens (nitrogen-rich, wet stuff like fruit/veg scraps, coffee grounds, fresh grass) and

browns (carbon-rich, dry stuff like dried leaves, shredded cardboard, straw, paper).

A classic target is roughly 25–30 parts carbon to 1 part nitrogen, which usually looks like adding

2–3 handfuls of browns for every handful of greens.

3) Choose your system: pile, bin, tumbler, worms, bokashi, or curbside

Don’t overthink itmatch the system to your life:

- Backyard pile/bin: best all-around, lowest cost.

- Tumbler: neater, faster mixing, often smaller capacity.

- Worm bin: perfect for apartments; produces rich castings.

- Bokashi: handles food scraps in a sealed container; great for small spaces and winter.

- Curbside/drop-off: easiest if availableno compost babysitting required.

4) Put your compost in the right location (or your future self will resent you)

For outdoor composting, pick a spot that’s convenient, drains well, and isn’t pressed against the neighbor’s fence like it’s trying to start drama.

Partial shade helps keep moisture and temperature steadier. If it’s a mile away from your kitchen, you’ll “forget” to use it (mysteriously, forever).

5) Start with a “brown base layer”

Begin with a thick layer of brownsdry leaves, shredded cardboard, small twigs. This improves airflow and absorbs moisture so your first week of scraps

doesn’t turn into compost soup.

6) Collect food scraps smartly (and with minimal stink)

Use a lidded container. To reduce odor and fruit flies, empty it every couple days or keep scraps in the freezer until drop-off day. Pro tip:

coffee grounds and a sprinkle of browns can reduce smell in the kitchen container.

7) Chop or tear larger pieces to speed things up

Compost microbes aren’t lazy, but they do appreciate smaller pieces. Chop thick stems, tear cardboard, and break up clumps. More surface area = faster

breakdown.

8) Layer greens and browns like you’re making lasagna (but for dirt)

Add a layer of greens, then cover with browns. If you’re tossing in wet scraps (melon rinds, pasta, etc.), increase the browns. The browns act like a

sponge and keep conditions aerobic.

9) Keep moisture at “wrung-out sponge” level

Too dry and decomposition crawls. Too wet and it goes anaerobic and stinky. Your compost should feel like a sponge you’ve squeezeddamp, not dripping.

If it’s soggy, add browns. If it’s dusty, add water and mix.

10) Add oxygen: turn, mix, or aerate regularly

Composting works best when oxygen can reach microbes. Turn a pile every 1–2 weeks for faster results, or mix whenever you add a new bucket of scraps.

Tumblers make this easy. Less turning still worksit just takes longer.

11) Know what NOT to compost (especially at home)

Backyard composting usually avoids items that attract pests or carry pathogens. Common “no” items:

meat, fish, dairy, oils/grease, pet waste, diseased plants, and treated wood.

Some municipal programs can handle more, but follow your local rules.

12) Handle “compostable” and “biodegradable” packaging carefully

Many compostable plastics are designed for industrial composting, not backyard piles. If your city accepts them, look for recognized

certifications (often tied to ASTM standards) and only include what your hauler or facility says they can process. When in doubt, leave it outcontamination

can ruin entire batches of compost.

13) Troubleshoot fast: smell, pests, and slow breakdown

Quick diagnosis:

- Rotten smell: too wet or too many greens. Add browns and mix.

- Fruit flies: bury scraps and cover with browns; keep a lid on indoor containers.

- Rodents: avoid meat/dairy/oils; use enclosed bins; bury food deeper.

- Not breaking down: pieces too large, too dry, or not enough nitrogenchop, moisten, and add greens.

14) Let it cure: finished compost needs a “rest period”

Compost isn’t done the second it looks dark. A curing phase helps stabilize it. Finished compost is typically crumbly, earthy-smelling, and no longer

resembles the original scraps (except maybe the occasional avocado stickerremove those when you see them).

15) Use your compost like a pro (and avoid rookie mistakes)

Compost is a soil amendment, not a replacement for soil. Use it to:

- Top-dress lawns and garden beds (a thin layer is plenty).

- Mix into planting holes or potting blends (often 10–30% compost by volume).

- Mulch around plants to retain moisture (keep it a few inches from stems).

Bonus: Three “Recycling” Paths People Forget

Community compost and gardens

Many community gardens accept drop-offs or run shared compost systems. It’s also a great way to learn what works in your local climatewithout reinventing

the compost wheel.

Worm composting (vermicomposting) for small spaces

Worm bins can be low-odor when managed well. Keep bedding damp, feed gradually, and avoid overloading. If the bin smells, it’s usually too much food,

not enough bedding, or not enough airflow.

Bokashi for food scraps (especially when you cook a lot)

Bokashi ferments food scraps in a sealed container using beneficial microbes. It’s handy when you want to process scraps indoors with minimal odor. The

fermented material is typically buried in soil or added (in small amounts) to an active compost system to finish breaking down.

Common Myths (That Make Composting Harder Than It Needs to Be)

Myth: Composting is only for people with big yards

Not true. Apartment composting is realworms, bokashi, and municipal programs exist for a reason. Your square footage does not get to decide whether your

banana peel lives a second life.

Myth: You must be perfect about ratios

Compost is forgiving. Aim for “more browns when in doubt,” keep it damp but not wet, and add air. If it smells bad, adjust and move on. Compost isn’t a

math testit’s a living system.

Myth: Composting always stinks

Healthy compost smells earthy. Bad smells usually mean too wet, too compacted, or too much food without enough browns. Fix the balance and it improves fast.

Real-World Experiences: What It’s Actually Like ()

The first time most people try to recycle biodegradable waste, they start with heroic optimism and a tiny container that fills up immediately. Day one:

you toss in coffee grounds and a banana peel and feel like a sustainability icon. Day three: you discover that onion skins are basically weightless but still

somehow take up all available space. Day five: you realize the real project isn’t compostingit’s building a routine that fits your life.

In practice, the biggest “aha” moment is learning that browns are the secret sauce. When a compost bin goes wrong, it’s usually because

it has the emotional energy of a swamp: too wet, too dense, not enough airflow. The fix is nearly always the sameadd dry leaves, shredded cardboard, or

paper and mix. People who keep a small stash of browns near the bin (a bag of leaves, a box of torn cardboard) succeed way more often than people who

try to wing it with only kitchen scraps.

If you’re in an apartment, the real-world experience often looks like this: you keep a small container in the freezer for scraps (no smell, no flies),

then empty it into a curbside organics bin or a drop-off bucket once or twice a week. The freezer trick feels odd at firstlike you’re roommates with

broccoli stemsbut it makes the whole system almost effortless. For people who prefer an indoor system, worm bins can be surprisingly chill: when fed

gradually and kept at a comfortable moisture level, they don’t smell, they don’t attract pests, and they turn food scraps into “garden gold.”

Bokashi is the “busy cook” favorite. Anyone who generates lots of scrapsespecially year-roundoften loves that bokashi is sealed, compact, and fast.

The learning curve is mostly about not overfilling and pressing scraps down properly. The trade-off is that bokashi isn’t finished compost by itself; it’s

a fermented pre-compost that needs soil or an active compost pile to fully break down. But for small kitchens, it can feel like the difference between

“I guess I’ll trash it” and “I can actually do this.”

The most relatable experience, though, is that composting makes you notice your waste. You start seeing patterns: how much food you toss, which

ingredients create the most scraps, and how quickly a bin fills when you cook from scratch. Many people end up reducing food waste just because composting

makes scraps visible. And when you finally spread finished compost in a planter or garden bed and the soil looks darker, holds water better, and plants

perk upyou get the quiet satisfaction of knowing your “trash” became something useful. It’s not just recycling. It’s a small, repeatable win.

Conclusion: Keep It Simple, Keep It Going

Recycling biodegradable waste isn’t about being perfectit’s about being consistent. Separate your scraps, balance greens with browns, keep the pile damp

and airy, and use the method that fits your space. Whether you compost in a backyard bin, feed worms under the sink, ferment scraps with bokashi, or use

curbside organics, you’re doing something that genuinely matters: keeping organics out of landfills and turning them into something that helps soil.