Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Meet the Algorithmic Architect: The “Ruined City” Generator

- Why These Cities Look Dystopian (Even If Nobody Typed “Make It Scary”)

- How an Algorithm “Builds” a City: The Three Big Approaches

- Where the Training Data Comes From (and Why That Matters)

- GANs, Diffusion Models, and the Rise of “Instant Dystopia”

- What These Cities Are Actually For (Besides Looking Cool on a Poster)

- The Uncomfortable Truth: Dystopian Cities Are a Mirror

- How to Make Your Own Dystopian Cityscape (Without Getting Zoning Approval)

- Conclusion: The City is Code, but the Meaning is Human

- Experiences: What It Feels Like to Build a Dystopian City with Code (500+ Words)

Imagine a city planner who never sleeps, never asks for funding, and absolutely refuses to attend community meetings. Now imagine that planner is an algorithm with a fondness for concrete canyons and “oops-all-windows” apartment blocks. That’s the vibe behind algorithm-built dystopian cityscapeseerily believable urban labyrinths that look like they were designed by a spreadsheet with trust issues.

These images aren’t just “AI did a cool thing.” They sit at the intersection of generative art, procedural modeling, architecture, and modern machine learningwhere a few rules, a random seed, and a lot of math can produce a skyline that feels like it’s one siren away from a curfew. Let’s unpack how these cities get built, why they look so unsettling, and what that tells us about the real cities we live in.

Meet the Algorithmic Architect: The “Ruined City” Generator

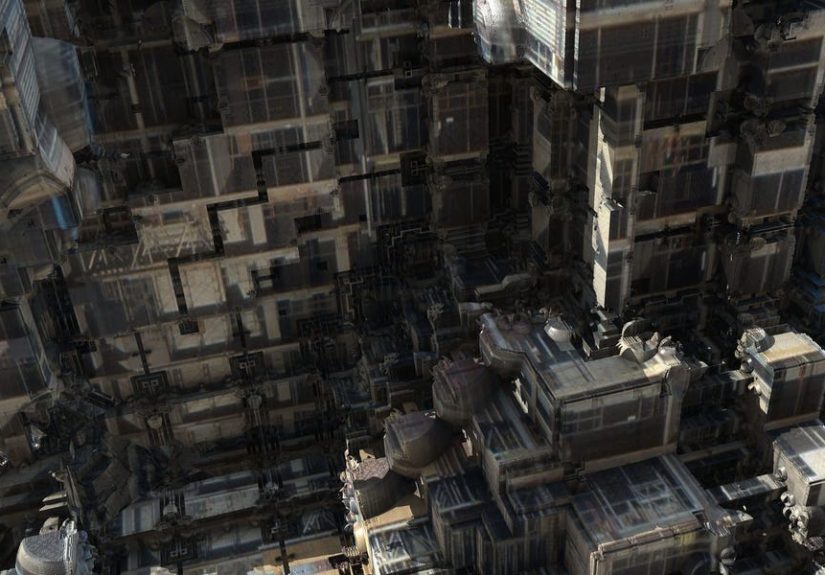

In 2016, coverage of designer and programmer Daniel Brown introduced a lot of people to a wonderfully unsettling idea: a computer program can “grow” entire cityscapes that look abandoned, overbuilt, and slightly impossible. Brown’s work is often described as dystopian or alienmassive structures, repetitive geometry, deep shadows, and that claustrophobic “Inception” sense that the laws of perspective are being politely ignored.

What makes the story particularly compelling is that this isn’t a one-click filter. The process is more like exploration. The program generates forms using fractal mathematics and randomness, and the artist navigates the resultschoosing, refining, and “mining” shapes that feel visually right. In one widely discussed series, the algorithm builds a structural framework and then overlays architectural texturethink tiny slices of apartment blocksso the final image reads as both mathematical and strangely human-made.

It’s also not an accident that the output feels “brutal.” Brown’s dystopian mood is strongly influenced by modernist and Brutalist architecturestyles that embrace raw materials, heavy forms, and repetition. When you combine those aesthetics with algorithmic scale (thousands of repeating elements) you get cities that feel monumental, impersonal, and a little judgmentallike they’re daring you to find the nearest exit.

Why These Cities Look Dystopian (Even If Nobody Typed “Make It Scary”)

Dystopia is often less about what’s present and more about what’s missing: warmth, human scale, variety, and a sense of welcome. Algorithm-generated dystopian cityscapes tend to accidentally nail those absencesbecause algorithms are very good at repetition, consistency, and extremes.

1) Scale without humans

Procedural systems love big numbers. A rule that produces one building can produce ten thousand. The result is often “hyper-density”: endless facades, stacked volumes, corridors that seem to go on forever. Human bodies aren’t there to act as visual punctuation, so the city feels like it’s been optimized for something elsemachines, gods, or an HOA from the underworld.

2) Brutalism: raw material + repetition = instant unease

Brutalist architecture is commonly associated with exposed concrete, bold geometric forms, and a “function over ornament” philosophy. Whether you love it or hate it, it has a recognizable visual language: blocky massing, deep-set windows, and repeating modules. When an algorithm leans into those traitsespecially repetitionthe mood can shift quickly from “architectural” to “ominous.”

3) The “Inception” effect: plausible detail, impossible space

One reason algorithmic city art feels uncanny is that it often combines realistic texture with space that doesn’t quite make sense. Your eye believes the surfaceswindows, balconies, concrete seamsthen realizes the geometry is bending or looping in ways real construction wouldn’t. That tension is a classic dystopian ingredient: the world looks familiar, but the rules are off by a few degrees.

4) Texture as memory

When generative cityscapes borrow textures from real-world apartment blocksespecially mid-20th-century concrete housingthe images inherit emotional baggage. Those facades carry cultural associations: urban renewal, mass housing, institutional authority, neglect, and (depending on your experience) nostalgia or dread. Algorithms don’t feel those associationsbut viewers do.

How an Algorithm “Builds” a City: The Three Big Approaches

Most algorithm-built cityscapes come from one (or a hybrid) of three approaches: procedural modeling, constraint-based generation, and machine learning image synthesis. Different tools, different philosophiessame outcome: a city you’d explore in a videogame, but maybe not as a long-term lease.

Approach A: Procedural generation (rules, grammars, and controlled chaos)

Procedural generation is the classic “city from rules” method. You define how streets branch, how blocks subdivide into lots, how buildings rise, and how details get applied. Tools used in professional pipelines often formalize this with a modeling pipeline:

- Start with a street network (grown by patterns, edited interactively).

- Generate blocks, then subdivide into lots.

- Apply building rules (shape grammars) to create detailed 3D models.

- Vary style and randomness by changing rule parameters and seeds.

This is why procedural city tools are so useful for urban design visualization and entertainment: once you have the rules, you can iterate fast. Change the “DNA” (a few parameters), and the city mutates in secondssame skeleton, new personality. It’s also why dystopia appears so easily: if your parameters favor density, repetition, and hard materials, the city becomes a concrete infinity pool (minus the water and the joy).

Approach B: Constraint-driven generation (pattern stitching and “smart” repetition)

Some systems generate cities by learning local rules from exampleshow pieces fit togetherthen assembling new layouts that obey those constraints. A popular way to explain this style of generation is the Wave Function Collapse family of algorithms: you provide a set of tiles (or building chunks) and adjacency rules, and the generator fills space while respecting constraints. The output can feel surprisingly coherent because it’s not purely randomit’s “random within allowed neighborhoods.”

This approach is especially common in games and interactive design tools because it produces believable structure with minimal hand-authoring. It can also create dystopia by accident: if your tiles are all “tower block, tower block, tower block,” the algorithm will obediently deliver the bleakest mixed-use development plan imaginable.

Approach C: Machine learning (AI image synthesis from data)

Machine learning systems can generate city imagery by training on large collections of real urban scenes. Instead of hand-coded rules like “streets make blocks,” the model learns statistical patterns: what buildings look like, where windows tend to be, how roads and sidewalks relate, how perspective works.

One influential direction is semantic-guided synthesis, where you provide a label map (road here, building there, sky above) and a model generates a photorealistic (or stylized) image from that structure. In other words: you lay down the urban blueprint as categories, and the neural network paints the city into existenceoften at impressive resolution.

Where the Training Data Comes From (and Why That Matters)

If you want an AI to generate convincing street scenes, you need exampleslots of them. Datasets for urban understanding exist specifically to teach models how cities look at pixel-level detail: cars, pedestrians, buildings, roads, signs. Some widely cited datasets were recorded across dozens of cities and include finely annotated images plus larger sets of coarsely labeled frames. That depth matters because it allows models to learn not just “city vibes,” but the structure that makes an urban scene readable.

Once a model learns those patterns, it can generate new imagesor, with the right architecture, let you manipulate content in meaningful ways. Research on urban-scene GANs has explored how to improve controllability (changing specific scene elements without breaking everything else) and maintain image quality. That’s a big deal if you’re using generated scenes for simulation, visualization, or training other computer vision systems.

GANs, Diffusion Models, and the Rise of “Instant Dystopia”

Two major families of generative AI show up in cityscape generation: GANs (Generative Adversarial Networks) and diffusion models. If procedural tools are “cities from rules,” these are “cities from learned patterns.”

GANs: the competitive art student phase

GANs work like a rivalry: one network generates images, another critiques them. Over time, the generator gets better at fooling the critic. GAN-based systems have been used to generate high-resolution scenes from semantic label maps, enabling interactive edits like adding, removing, or changing objects in a scene while keeping the overall image coherent.

In urban terms, GAN workflows can feel like “Photoshop with a planning department.” You sketch the structure, the model fills in the details. Want more buildings? Shift the labels. Want fewer cars? Remove those regions. The model tries to keep upsometimes beautifully, sometimes with the architectural integrity of a cardboard diorama in a rainstorm.

Diffusion models: the patient sculptor phase

Diffusion models generate images by starting from noise and gradually denoising toward a coherent picturelike sculpting a skyline out of static. Modern diffusion systems are a big reason text-to-image tools became so capable: they’re great at producing crisp detail, coherent lighting, and consistent style. For dystopian cityscapes, diffusion models are basically a cheat code: prompt a mood (“brutalist megacity at dusk, endless concrete, cinematic haze”) and you’ll often get something that looks like a movie still from a future where sunlight is a subscription.

Creative platforms increasingly offer access to multiple generative models in one place, making it easy for artists to iterate quickly, remix styles, and move from concept to polished output in minutes rather than days.

What These Cities Are Actually For (Besides Looking Cool on a Poster)

Algorithm-generated cityscapes aren’t just aesthetic experiments. They have practical uses across industriesand the dystopian flavor is often a stylistic choice, not the only destination.

Film, games, and concept art

Entertainment pipelines love fast iteration. A director wants “denser,” a game designer wants “more vertical,” an art director wants “less Blade Runner, more bureaucratic nightmare.” Procedural and generative tools can produce dozens of variations rapidlythen a human selects and polishes the best ones.

Urban design visualization

Professional city modeling tools can generate and iterate urban environments from real GIS data or synthetic scenarios, letting planners and designers explore alternatives quickly. Change zoning assumptions, adjust building styles, rerun the rules, compare outcomes. It’s not dystopia; it’s iterationthough, yes, the wrong parameter can accidentally invent a neighborhood with the charm of a parking garage.

Generative design as search (not decoration)

Generative design in architecture and construction is often framed as exploration and optimization: define goals and constraints, then let software produce a wide range of solutions. The “design” is less a single drawing and more a space of possibilities. Humans remain the decision-makers, but algorithms expand the menu dramatically.

Synthetic data for training AI

Urban-scene generation can produce training data for computer visionuseful when real-world data is expensive to label or hard to collect for edge cases. The catch: synthetic data must be realistic and diverse enough to help, not confuse, the systems trained on it.

The Uncomfortable Truth: Dystopian Cities Are a Mirror

Here’s the part where the neon sign flickers and the essay gets a little too real: algorithmic dystopias work because they exaggerate patterns we already recognize.

- Repetition becomes a metaphor for bureaucracy and mass production.

- Oversized structures dwarf the individual, echoing institutional power.

- Missing greenery and softness reads as neglect or control.

- Endless density feels like scarcity packaged as progress.

Even when an artist is “just playing with code,” audiences read meaning into the output. That’s not a bug; it’s how visual storytelling works. The algorithm supplies form. Humans supply interpretationand we are extremely talented at sensing when a place feels like it doesn’t want us there.

How to Make Your Own Dystopian Cityscape (Without Getting Zoning Approval)

If you want to experimentwhether with procedural generation, generative AI, or bothhere’s a practical mental model. No brand loyalty required, and no hard hat necessary.

Step 1: Decide what kind of dystopia you mean

“Dystopian” can mean many things. Pick a lane:

- Brutalist megastructure: repetition, concrete, deep shadows.

- Cyberpunk canyon: vertical density, signage, wet reflections.

- Abandoned modernism: clean forms, decay, overgrowth.

- Impossible geometry: Escher angles, looping corridors, spatial tricks.

Step 2: Build the macro (streets and massing)

Procedural tools often start with streets, blocks, and lots. If you’re using AI image tools, you can still think this way: establish big shapes first, then let detail follow. The dystopian look usually comes from a few macro choices: density, verticality, and tight negative space.

Step 3: Add rules (or prompts) that enforce repetition

Repetition is the fastest route to “systemic.” In procedural workflows, use modular elements and simple grammars. In AI workflows, prompt for repeating windows, stacked slabs, modular concrete panels, and “institutional scale.” Then vary the seedbecause the seed is your parallel universe generator.

Step 4: Break it (tastefully)

The best dystopian cityscapes often have one “wrong” thing: a tilt, a fold, an impossible stack. Add subtle distortionsperspective shifts, gravity-defying overhangs, or corridors that don’t resolve. Too much and it becomes fantasy. Just enough and your viewer’s brain whispers, “Something’s off,” which is basically the dystopia slogan.

Step 5: Curate like an editor, not an engineer

Whether you’re exploring procedural outputs or generating dozens of AI variations, the secret skill is selection. Most results will be fine. A few will be haunting. Save the haunting ones.

Conclusion: The City is Code, but the Meaning is Human

Algorithm-built dystopian cityscapes are more than a tech trick. They’re a collaboration between systems that generate structure and people who recognize stories in that structure. Procedural rules can scale a skyline into infinity. GANs can paint photoreal streets from labels. Diffusion models can turn a sentence into a metropolis. But the reason these cities stick in your mind is simpler: they compress real architectural anxieties into a single imagedensity, power, repetition, and the fear of being reduced to a tiny dot between tall walls.

And maybe that’s why they’re so addictive to look at. They’re not predictions. They’re pressure tests for imaginationshowing what happens when we hand the keys to the city to math, then ask our emotions to move in.

Experiences: What It Feels Like to Build a Dystopian City with Code (500+ Words)

If you’ve never tried generating a cityprocedurally or with generative AIhere’s the most honest preview: it starts as “I’ll test this for five minutes,” and ends as “Why is it midnight and why do I have 86 versions of the same alley?” That time-warp effect is part of the charm. City generation is less like drawing and more like archaeology in reverse: you keep digging until you uncover something that looks like it’s always existed.

The first experience most creators report is the shock of scale. You adjust one parameterstreet frequency, building height variance, modular repetitionand the world changes immediately. It’s empowering in a way that traditional illustration isn’t. In a normal workflow, making a city denser means drawing (or modeling) a lot more. In a procedural workflow, “denser” is a number. Suddenly you’re not placing buildingsyou’re defining a rule that places buildings. It’s the difference between planting trees and inventing a climate.

Then comes the part that feels suspiciously like personality testing: the seed. Random seeds are not just technical details; they’re alternate timelines. One seed gives you a coherent downtown grid. Another gives you a knot of streets that looks like it was designed by a stressed-out spaghetti noodle. With AI image generation, seeds (or variations) do the same thing: you’ll get outputs that are technically “correct” yet emotionally flat, and then, out of nowhere, a version that feels loaded with narrativelike a place where something happened and nobody is talking about it.

The third experience is learning that dystopia is mostly composition. You don’t need skulls, smoke, or dramatic lightning. Often, dystopia emerges from three quiet choices:

- Compression: narrow gaps between tall forms, minimal sky.

- Repetition: modular windows and identical slabs that imply systems over individuals.

- Material cues: concrete, metal, glasssurfaces that feel cold even in a still image.

Once you notice this, you start “directing” the generator. You’ll deliberately reduce variety to make the city feel controlled, then add one odd disruptiona tilted block, an impossible bridge, a courtyard that shouldn’t fitso the viewer senses a rule and then sees that the rule can be broken. That tension is where the mood lives.

Finally, the experience becomes surprisingly philosophical: you stop thinking like a builder and start thinking like a curator. The generator produces options. Your job is to recognize which option has story. This is true in procedural workflows (where you explore a generated structure and choose frames or angles) and in AI workflows (where you sift through variants and keep the ones that feel inevitable). The best results often don’t look “perfect.” They look lived-inor abandonedbecause tiny irregularities give the scene plausibility.

If you try one simple experiment, make it this: generate 20 variations of the same city rules or prompt. Don’t keep the “most realistic.” Keep the one that makes you pause. The one that feels like a location in a film you haven’t seen yet. That pause is the real outputthe moment your brain turns geometry into meaning. The algorithm built the cityscape, sure. But you built the dystopia.