Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why FDM Prints Break Where They Break

- What “Brick Layers” Means in 3D Printing

- Why Brick Layers Can Make Prints Stronger

- Where Brick Layers Really Shines

- The “Nice Things” Problem: Why It’s Not in Every Slicer Yet

- Brick Layers Isn’t a Cheat Code: Tradeoffs and Limitations

- How to Think About Strength Like a Grown-Up (Without Becoming Boring)

- So… Is Brick Layers Worth It?

- Conclusion

- Experiences From the Real World: What Chasing “Stronger Prints” Actually Feels Like (Extra )

If you’ve ever snapped a 3D-printed part and thought, “Wow, it failed exactly where the layers are,” congratulationsyou’ve discovered

the ancient, unbreakable law of FDM printing: the Z direction is where dreams go to delaminate.

We can tune temperatures, change orientations, add walls, and pray to the calibration gods… but the fundamental problem remains:

layer-by-layer parts tend to be strongest along the roads of extruded plastic and weakest between them.

Enter “brick layers,” a slicing concept that sounds like a home renovation show but is really a clever trick to make printed walls interlock like masonry.

The punchline? The technique is practical, software-friendly, and testedyet it’s oddly missing from many mainstream slicers.

Why? A mix of patents, platform caution, and the timeless human tradition of turning simple things into complicated things.

(We can’t have nice things. But we can at least understand why.)

Why FDM Prints Break Where They Break

FDM/FFF printing builds parts by laying down hot plastic “roads” (beads/rasters) in one layer, then stacking the next layer on top.

Inside a single layer, adjacent roads press together while still warm. Between layers, bonding depends on heat, pressure, time, and

polymer chains diffusing across the interface. If the interface cools too fastor if there are tiny voidsbonding suffers.

That’s why many FDM parts are anisotropic: they don’t have the same strength in every direction.

The XY plane (along the extruded roads) typically performs better, while the Z direction often becomes the “weak link”

because it relies more heavily on interlayer adhesion.

Research and industry documentation have pointed to the same culprits over and over:

imperfect layer contact, voids, thermal gradients, and process parameters (temperature, speed, layer height, extrusion width)

that change how well layers fuse together. In other words, the part isn’t “one piece of plastic” so much as “a polite stack of noodles

trying very hard to become one piece of plastic.”

What “Brick Layers” Means in 3D Printing

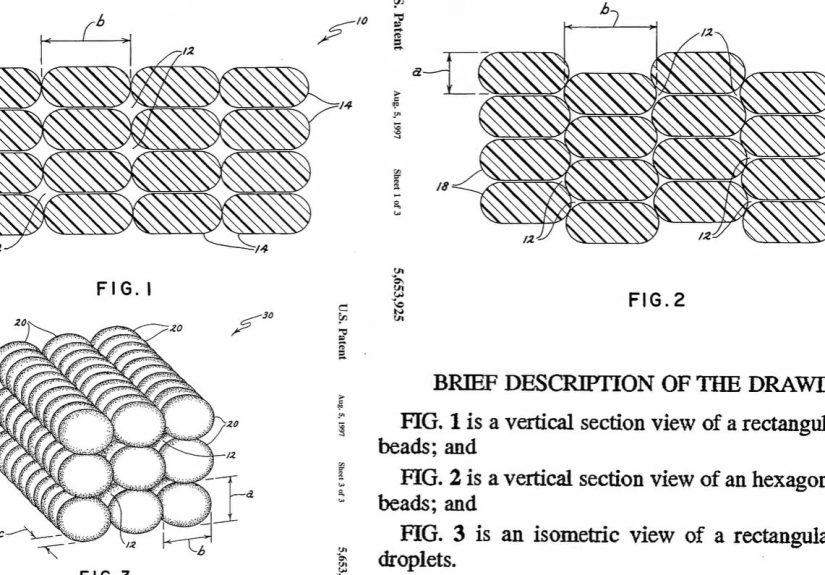

Brick layers (also called “brick layer slicing” or “interlocking layers”) is a toolpath strategy for FDM prints where walls (and sometimes infill)

are arranged so successive layers don’t align into one continuous, flat “failure plane.”

Instead of stacking perimeters directly on top of each other like identical pancakes, the layers are staggered so they interlocklike a brick wall’s

running bond pattern.

The basic idea

- Standard slicing: Perimeters line up vertically, creating a continuous seam-like plane that can shear apart under load.

- Brick layers: Perimeters are vertically offset and shaped so each layer “keys into” the one below, increasing interlock and disrupting a clean fracture path.

There are multiple ways to get “brick-ish” behavior, depending on the implementation:

some approaches alter bead height/positioning so adjacent layers aren’t centered the same way;

others stagger wall geometry or alternate how material is placed so the boundary between layers becomes more complex than a single flat interface.

Why Brick Layers Can Make Prints Stronger

Brick layers aims to improve strength with two big benefits:

(1) mechanical interlocking and (2) better distribution of stress.

If a part tries to split along the layer boundary, it can’t just “zip” cleanly across a flat plane.

Instead, the crack has to navigate a more tortuous pathlike trying to tear a woven fabric versus a neat sheet of paper.

1) It breaks the “easy tear line”

In many failures, the crack follows the simplest route: the layer interface.

Brick layers disrupts that route by offsetting where the weak interfaces line up.

Even if interlayer adhesion is unchanged, the geometry itself makes failure less straightforward.

2) It can increase bonding surface area (in practice)

When walls interlock, the contact between layers is no longer a simple, flat-ish boundary.

Depending on bead shape and overlap, the effective bonded area can increaseand larger bonded interfaces generally provide more opportunity

for fusion and load transfer (assuming the material is deposited hot enough to actually bond).

3) It helps where walls matter most

Lots of “real-world” functional printsbrackets, clips, housingsget most of their strength from perimeters (walls),

not from the infill. Brick layers targets the part you’re already relying on.

It’s not magic. It’s just focusing effort where your failure is most likely to start.

Where Brick Layers Really Shines

Thin-walled functional parts

If you print with low infill or even “vase-mode-adjacent” wall-heavy designs, wall behavior dominates.

Brick layers can be especially interesting for parts where you want strength without dramatically increasing infill percentage.

Parts that fail in shear at layer lines

Think of a clip that snaps when bent, or a bracket that fractures where a screw load concentrates.

If the failure is repeatedly occurring along a clean layer plane, interlocking geometry can help.

If the part fails by crushing, buckling, or tearing within the layer roads themselves, brick layers may do less.

Water-tightness and pressure resistance (sometimes)

Many FDM leaks happen along subtle gaps between roads and layers.

Interlocking walls can reduce continuous leak pathwaysespecially if paired with sensible choices like more perimeters,

tuned flow, and appropriate materials. Some makers are even experimenting with brick-layer strategies for waterproof hulls

and submersion-style tests, where tiny paths for seepage really matter.

The “Nice Things” Problem: Why It’s Not in Every Slicer Yet

Here’s the frustrating part: brick-layer concepts aren’t new, and the community has discussed them for years.

Yet widespread, polished “one-click” support in mainstream slicers has been slow. A major reason frequently cited in maker discussions

is patent uncertainty.

A tale of two patents (and one big chilling effect)

In simple terms, the story goes like this:

an older Stratasys patent from the 1990s described bead/layer arrangements that resemble brick-layer ideas, and it eventually expired.

Then, a newer patent was filed in 2020 that also covers altering bead profiles/positions to improve shear strength, raising concerns about whether

implementing similar features might create legal riskespecially for commercial software and companies.

Whether a newer patent is truly valid in light of prior art is the kind of thing that gets decided slowly, expensively, and usually with lawyers

billing in units of “yikes.” Open-source and commercial slicer teams often prefer avoiding ambiguous legal territory, which can delay features even when

users want them yesterday.

The end result is classic: the technical path is clear, the benefits are real, but adoption is slowed by the ecosystem’s invisible forceslegal risk,

corporate caution, and the fact that adding a feature to a slicer isn’t just “flip a switch,” it’s “support it forever.”

Brick Layers Isn’t a Cheat Code: Tradeoffs and Limitations

It may change surface appearance

If walls interlock, you can get subtle texture changes on vertical surfaces. Sometimes that’s fine. Sometimes it’s ugly.

(And yes, “ugly but strong” is still a valid engineering aesthetic.)

It can complicate dimensional accuracy

Any time you alter bead placement, you risk changing how sharp corners, holes, and thin features resolveespecially if extrusion isn’t perfectly tuned.

On parts requiring tight tolerances, you may need to test and compensate.

It won’t fix poor layer adhesion

Brick layers helps you avoid a single, continuous failure plane, but it doesn’t magically solve low-temperature printing,

drafty enclosures, wet filament, under-extrusion, or a nozzle that’s basically doing interpretive dance.

If your layers barely bond, interlocking geometry can’t force polymer chains to become best friends.

Some implementations are clunky today

Without native slicer support, people rely on workarounds like post-processing scripts or multi-process tricks.

That can introduce quirkslike breaking certain printer “cancel object” features or adding another step to your workflow.

Not impossible, just… very on-brand for hobby 3D printing.

How to Think About Strength Like a Grown-Up (Without Becoming Boring)

If your goal is “stronger prints,” brick layers is one tool in a larger toolbox. The best results usually come from stacking strategies:

design choices, orientation, material selection, and print settings that align with how the part is loaded.

Strength stack: what often matters most

- Orientation: Align the strongest direction (along extrusion paths) with the main load whenever possible.

- Walls/perimeters: Extra walls often outperform extra infill for many functional parts.

- Temperature and cooling control: Hotter (within material limits) and less aggressive cooling can improve bonding for some plastics.

- Extrusion consistency: Good flow calibration reduces voids and improves contact between roads.

- Material choice: Some filaments bond between layers better than others; pick based on load and environment.

- Post-processing: Annealing or other treatments can help specific materials, with predictable dimensional side effects.

- Geometry upgrades: Fillets, ribs, and thicker sections at stress points beat “just crank infill” more often than people want to admit.

Brick layers fits into this as a “geometry of deposition” upgradeparticularly attractive because it doesn’t require new hardware.

It’s a software idea with hardware consequences, which is basically the most satisfying type of idea.

So… Is Brick Layers Worth It?

If you’re printing decorative models, probably not. If you’re printing functional parts that fail along layer lines,

it’s absolutely worth understandingand testing on your own printer/material combinations.

The most honest answer in 3D printing is always: “It depends, now print two versions and break them like a scientist.”

Brick layers isn’t the end of the story for stronger FDM parts, but it is a rare thing in maker-land:

a clever concept that’s both easy to explain and genuinely useful.

The main tragedy is that broad, native support has been slowed by non-technical friction.

Which is why we can’t have nice thingsat least not without a side quest.

Conclusion

Brick-layer slicing is a practical, physics-friendly approach to one of FDM’s oldest problems: parts that fail too easily along layer lines.

By staggering and interlocking walls, you can reduce clean fracture planes and sometimes improve real-world durabilityespecially in wall-driven prints.

The technique has momentum in the community, proof-of-concept testing, and active experimentation.

What it needs next is wider, polished slicer support and clearer pathways through the legal and product-maintenance realities of software.

Experiences From the Real World: What Chasing “Stronger Prints” Actually Feels Like (Extra )

Ask a room full of makers about “strength,” and you’ll get a surprisingly emotional response. Not because tensile tests are romantic,

but because everyone has a story about a part that failed at the exact wrong time. A drawer latch that snapped during installation.

A camera mount that held perfectlyuntil the first bumpy ride. A bracket that survived the bench test and then exploded the moment

a screw tightened down. The common theme is always the same: the print looked solid, but the layers had other plans.

That’s why brick layers gets people excited. It’s one of those rare ideas that triggers an immediate “Wait… why aren’t we doing that already?”

reaction. The first experience many people report is simply visual: once you understand that standard slicing stacks identical layer outlines,

you can’t unsee the built-in crack path. Brick layers reframes the print as a structure, not just a shapemore like a laminate or a masonry wall.

Even before you test anything, you feel like you’re finally speaking the printer’s native language.

The next experience is usually the “workflow reality check.” Makers try to find the setting, don’t see it, then discover the ecosystem’s patchwork:

forum threads, scripts, post-processing steps, and experimental profiles. Some people love this phase because it feels like hacking the matrix.

Others hate it because they just wanted a stronger clip, not a minor in toolpath archaeology. Either way, it teaches an important lesson:

strength improvements often arrive as process improvements, not just a checkbox.

Then comes the testing phasethe most satisfying part, because it replaces internet certainty with physical truth.

People commonly print a pair of identical parts: one standard, one brick-layered. They flex them by hand, clamp them, load them with weights,

or do the most scientific test of all: “try to break it while muttering about how much filament it wasted.”

The interesting reports tend to be nuanced. Brick layers can make a part feel less “snappy” and more “stubborn.”

Instead of a clean split along one layer line, you might see a more jagged failure, or a part that deforms longer before giving up.

That kind of failure behavior matters in real use, because a part that gives warning is often better than a part that fails instantly.

The most relatable experience, though, is the conversation that happens after: the maker explaining to a friend why the “same material” can behave so differently.

Brick layers becomes a teaching moment about anisotropy, load paths, and how design and manufacturing are inseparable.

It turns “3D printing” from a craft into a mini engineering lab. And that’s the best case scenario: not just stronger parts,

but a stronger understanding of why parts behave the way they do.

Finally, there’s the community experienceequal parts hopeful and exasperated.

When a technique works, people want it to become normal. They want slicers to support it natively, printers to preview it cleanly,

and profiles to exist without duct-tape scripts. Brick layers feels like it deserves to be “boring technology,” the kind you take for granted.

The fact that it’s not yet boring is exactly why it sparks discussionand why so many makers keep testing, sharing results,

and pushing for better implementations. Nice things may take time. But makers are stubborn, and stubborn is basically a structural material.