Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- The blackout in one paragraph (because your phone is at 12%)

- Ohm’s law: the “tiny” equation that explains a lot of big blackouts

- How the Northeast blackout of 2003 started: a short timeline with big consequences

- The computer problems: when the grid’s “notification system” goes dark

- The tree problem: vegetation management meets I²R heating

- Cascade failures: how the grid falls like dominoes (but with math)

- Human factors and “organizational impedance”

- Lessons learned: what the blackout changed (and why you should care in 2026)

- Ohm’s law meets outage prevention: a practical cheat sheet

- Wrapping it up: the 2003 blackout as a systems story

- Extra: Experiences that capture what cascade failures feel like (500-word add-on)

On August 14, 2003, a whole lot of the U.S. and Canada learned the same lesson at the same time:

electricity is the quiet friend who does everythinguntil it doesn’t. In minutes, the grid across

parts of the Midwest and Northeast unraveled into the largest power outage in North American history.

The story is famous for its “how did a few things go wrong and then everything went wrong?”

energyplus a cameo by a computer alarm system that basically hit snooze at the worst possible moment.

This article breaks down the Northeast blackout of 2003 in plain American English (with a tiny bit of

physics), focusing on three big ideas that explain the whole mess: cascade failure dynamics,

control-room computer problems (SCADA/EMS alarms), and the electrical fundamentals behind it all,

including Ohm’s law and why power lines get hot, sag, and trip.

The blackout in one paragraph (because your phone is at 12%)

A stressed grid in the afternoon heat. A major generator trips. A control-room alarm and logging system fails.

Transmission lines in northern Ohio begin tripping after contacting overgrown trees. Operators and coordinators

don’t fully seeor act onthe developing emergency fast enough. Power flows reroute, lines overload, voltages

wobble, protective relays do their job (a little too enthusiastically), and the problem cascades across a huge region.

If you’ve ever watched one shopping cart bump another and somehow the entire parking lot becomes a domino show…

it’s like that, but with electrons.

Ohm’s law: the “tiny” equation that explains a lot of big blackouts

If the phrase “Ohm’s law” gives you flashbacks to a quiz you didn’t study for, breathe. You only need the

common-sense version. The grid isn’t magic; it’s physics plus procedures plus software plus humans trying to do

a thousand things at onceaccuratelywhile the system changes every second.

Ohm’s law in one line: V = I × R

Voltage (V) is the push, current (I) is the flow, and resistance (R) is the opposition.

If demand rises or the network changes, currents shift. And when current rises, two important things happen:

the grid heats up and the voltage situation can get touchier.

The heat part: why “I²R” is the villain’s catchphrase

Power lost as heat on a conductor is proportional to I²R. That square matters. A modest jump in current

can create a much bigger jump in heating. Heating makes lines expand and sag. Sag can reduce clearance to trees.

And when a high-voltage line touches vegetation, protective relays trip it offlinefastbecause “not starting

a forest fire” is a top-tier grid feature.

The AC part: impedance, reactive power, and why voltage stability gets weird

Real grids use alternating current (AC), so the “R” in Ohm’s law becomes part of a bigger concept called

impedance (resistance plus reactance). Here’s the practical takeaway: you don’t just need enough megawatts

(real power) to run things. You also need enough reactive power (often measured in MVAr) to keep voltages

in a safe range and move real power reliably.

Under heavy loading, reactive power demand increases sharplyoften roughly with the square of currentso a grid

that’s already strained can run short on voltage support right when it needs it most. Also, reactive power doesn’t

“travel” well over long distances, which means urban and heavily loaded areas can become more susceptible to

voltage instability during stressful conditions.

How the Northeast blackout of 2003 started: a short timeline with big consequences

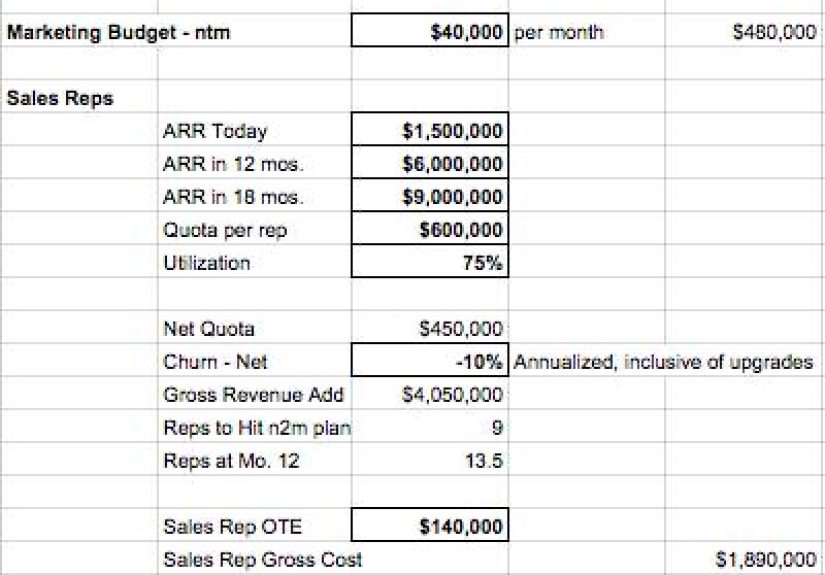

The 2003 event is a textbook case of “many small issues lining up like they rehearsed.” Key milestones often cited

in official summaries look like this:

| Time (EDT) | What happened | Why it mattered |

|---|---|---|

| 12:15 p.m. | MISO’s state estimator becomes ineffective due to bad input data. | A major monitoring/analysis tool is compromised right when conditions are tightening. |

| 1:31 p.m. | A major FirstEnergy generating unit (Eastlake 5) trips offline. | Power flows reroute; the transmission system has to carry more load differently. |

| Shortly after 2:14 p.m. | FirstEnergy’s control-room alarm and logging system fails. | Operators lose a critical “heads-up display” for rapidly changing grid conditions. |

| After 3:05 p.m. | Multiple 345-kV lines begin tripping after contacting overgrown trees. | Each line loss forces more current onto what remains, increasing overload risk. |

Notice the pattern: monitoring problems + reduced generation + reduced visibility + line trips. That’s the

recipe for a cascade failureespecially in a tightly interconnected system where power is constantly finding

the path of least impedance, not the path that makes humans feel relaxed.

The computer problems: when the grid’s “notification system” goes dark

A major headline from the investigations was not “hackers,” “mystery EMP,” or “aliens with a grudge.”

It was a much more ordinary nightmare: a critical software system in a control room stopped providing

alarms and meaningful situational awareness. Think of it as flying a plane and discovering that your warning

lights, gauges, and half your instruments are quietly lying to youor just not updatingwhile you’re still expected

to land safely.

SCADA/EMS alarms: why they exist

Control rooms depend on SCADA (Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) and EMS (Energy Management Systems)

to gather real-time measurements and flag problems. Humans can’t watch every voltage, every line flow, and every

contingency at once. Alarm systems exist to spotlight what matters now.

What went wrong in 2003

During the developing emergency, the FirstEnergy alarm processing application stalled and the system experienced

server failures, including failureover complications. Remote terminals and data links had issues, and the loss of

alarm functionality meant operators did not receive normal visual/audible warnings. The result was delayed recognition

of the severity of grid conditions and delayed corrective actionsexactly the kind of delay a cascade failure loves.

This wasn’t a single “oops.” It was a chain inside the chain: the alarm application stalled, a primary server failed,

the system failed over, and the backup server later failed tooleaving operators with a slower, less trustworthy view

of what was happening. The grid doesn’t pause politely while IT troubleshoots.

The tree problem: vegetation management meets I²R heating

Yes, trees played a starring rolebecause physics doesn’t care that a branch is “basically not touching.”

Under heavy load, lines heat and sag. Clearance shrinks. If the vegetation underneath is overgrown, the line can

contact it. Protective relays will trip the line to prevent damage and hazards. But every time a major line trips,

the power that used to go through it has to go somewhere else.

That “somewhere else” is usually the neighboring transmission network. Flows increase on remaining lines, which

can make those lines heat more, sag more, and approach their own protection limits. In other words: one trip can

make the next trip more likely. That’s a cascade failure in action.

Cascade failures: how the grid falls like dominoes (but with math)

A cascade failure isn’t one giant component breaking. It’s a sequence of smaller failures that amplify each other.

On a large interconnection, the power system is constantly balancing supply and demand. When something changes

a generator trips, a line trips, a voltage dropspower flows redistribute almost instantly.

Overloads and redistribution: the “water pipe” analogy (with a warning label)

People often describe the grid like water pipes: block one pipe, water reroutes. That’s useful, but incomplete.

Electricity doesn’t just choose one alternate pipe; it spreads across many paths according to impedance. If a big

transmission path trips, multiple neighboring elements can see higher flows. If the grid is already heavily loaded,

those elements might exceed safe operating limits quickly.

Voltage instability: when you have “enough power” but still lose the grid

Here’s a subtle point: you can have plenty of generation overall and still suffer a collapse if voltage support

and reactive power aren’t managed effectively in the right locations. Heavy current increases reactive power demand,

and reactive power is hard to ship over long distances. If voltages start to sag, equipment may trip to protect itself,

which can further worsen flows and voltages.

Human factors and “organizational impedance”

Even the best engineers can’t out-run missing data, broken alarms, and confusing coordination. Reports after 2003

emphasized that multiple organizations were involvedutilities, reliability coordinators, neighboring operatorsyet

no single party had a complete, real-time picture quickly enough to stop the sequence once it accelerated.

In plain terms: the grid needed fast, decisive, coordinated action. Instead, it got partial information, delayed

recognition, and a system moving too quickly for manual, phone-based understanding to keep up. Humans weren’t the

“cause” in a cartoon-villain sense; they were part of a complex system that didn’t give them the tools and clarity

they needed at the moment it mattered most.

Lessons learned: what the blackout changed (and why you should care in 2026)

The 2003 Northeast blackout didn’t just become a documentary favorite. It drove serious changes in how reliability

is handled across North America. Investigators emphasized that the blackout was preventable and called for stronger

compliance with reliability requirements, better tools, better training, and better oversight.

Reliability standards and accountability

One major theme: reliability rules can’t be “optional vibes.” The aftermath pushed toward mandatory compliance and

meaningful consequences for non-compliance, rather than relying on informal norms and best-effort guidelines.

Control-room tools that must not fail silently

Recommendations included fixing known EMS alarm processor issues, improving reliability monitoring tools (like state

estimation and contingency analysis), and ensuring these tools run reliably and frequently enough to be operationally

useful. The goal is simple: operators should never be forced to run a high-speed, high-stakes system with

low-confidence visibility.

Training and drills that feel real (because the grid will)

Another theme: realistic emergency simulations and drills. Cascades move fast. You can’t “learn the rhythm” of a

cascade for the first time during an actual cascade. Training needs to rehearse communication, decision-making,

and technical actions under pressurelike a fire drill, but with more spreadsheets and fewer marshmallows.

Vegetation management: unglamorous, non-negotiable

Tree trimming is not a side quest. It’s core reliability work. Transmission line clearances exist for a reason,

and the laws of heating and sagging do not accept apology letters. Good vegetation management reduces the chance

that a heavily loaded, sagging line becomes the first domino.

Ohm’s law meets outage prevention: a practical cheat sheet

- Higher current means much higher heating (I²R): overloaded lines don’t just run “a little warmer.”

- Hotter lines sag more: clearance to trees shrinks right when the grid is stressed.

- Reactive power matters: voltage stability can fail even when total generation seems “enough.”

- Alarms are safety equipment: if they fail, it must be loud, obvious, and quickly recoverable.

- Cascades accelerate: delayed awareness and delayed action can turn “manageable” into “regional.”

- Coordination is a grid component: unclear roles and fragmented visibility act like extra impedance in decision-making.

Wrapping it up: the 2003 blackout as a systems story

The Northeast blackout of 2003 is sometimes told as a weird chain of bad luck. A better framing is that it’s a

systems story: engineering, software, operations, maintenance, and coordination all interacting in a high-speed,

tightly coupled machine. When those layers align in the wrong way, the grid can lose its ability to absorb routine

disturbancesand a cascade failure takes the wheel.

And yes, Ohm’s law belongs in the conversation. Not because V = I × R is secretly magical, but because it reminds us

that the grid’s behavior is rooted in physical reality: currents heat conductors, voltage needs support, and power

flows follow impedance. Pair those realities with reliable tools, disciplined maintenance, and coordinated operations,

and you get a grid that can bend without breaking.

Extra: Experiences that capture what cascade failures feel like (500-word add-on)

If you want to understand cascade failures emotionallynot just technicallyimagine you’re watching a situation

that changes faster than human intuition. A cascade doesn’t feel like one dramatic snap. It feels like a room full

of small, urgent signals that suddenly stop making sense.

In a control room, the first “experience” is often uncertainty. You’re used to alarms and logs narrating the grid’s

mood: line loading creeping up, voltages nudging down, a piece of equipment complaining. Now picture the alarms

going quietnot because everything is fine, but because the messenger fainted. Phones ring. Neighboring operators

ask questions that sound simple (“What’s the status of that line?”) and suddenly aren’t. The operators don’t feel

lazy or careless; they feel like they’re trying to drive in heavy rain after someone smeared sunscreen on the windshield.

Out on the system, the cascade is experienced as a relentless reshuffling of power flows. When one line trips,

the “new normal” isn’t stableit’s just the next temporary arrangement. Protective relays act like vigilant bouncers:

if a line is overloaded or voltage is outside limits, they remove it from the party. That keeps equipment safe,

but it also concentrates the remaining flows onto fewer paths. Heat builds. Sag increases. A different line gets

closer to its limit. And thenanother trip. The rhythm speeds up. Once enough elements are gone, there’s no

comfortable configuration left.

Meanwhile, everyday life experiences the blackout as a strange mix of inconvenience and vulnerability. Offices empty

early. Elevators stop. Subway platforms get crowded. Restaurants switch to “cash only” (until the cash register battery

gives up too). Traffic lights blink out, and suddenly every intersection becomes a group project. People with medical

devices or temperature-sensitive medications worry first, not last. Hospitals and critical facilities shift to backup

systems, which feels reassuringuntil you remember backup power is designed for resilience, not for comfort.

There’s also a social experience: the sudden return of the neighborhood. People step outside because the inside is hot

and quiet, and because the outside is where you confirm you’re not the only one living in a candlelit reboot. Someone

shares a portable radio update. Someone else jokes that they finally found the “off” switch for the internet. It’s funny

until the freezer starts thawing and you realize your entire modern routine is a stack of assumptions built on steady,

invisible power.

The lasting experiencelong after the lights returnis respect for boring excellence. You start noticing tree trimming

near power lines. You care about the words “operator training” and “alarm redundancy.” You realize that a stable grid

isn’t just hardware; it’s maintenance schedules, software quality, clear communication protocols, and people who can

interpret a fast-moving system under pressure. Cascade failures teach an uncomfortable truth: reliability is not a

single upgrade. It’s a habit.