Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Is a Differential Diagnosis (DDx), Exactly?

- Why Differential Diagnosis Matters More Than You’d Think

- How Clinicians Build a Differential Diagnosis

- Tools Clinicians Use to Avoid Missing Something

- Differential Diagnosis Examples (Step-by-Step)

- How Tests Fit Into Differential Diagnosis (Without Turning You Into a Lab Report)

- Common Cognitive Pitfalls (and How Clinicians Try to Dodge Them)

- What Patients Can Do to Help the Differential Diagnosis Process

- Key Takeaways

- Experiences Related to Differential Diagnosis ()

If you’ve ever Googled a symptom and ended up convinced you have a rare condition usually found in “one documented case in 1973,” congratulations: you’ve experienced the chaotic

cousin of clinical reasoning. In real healthcare, clinicians use a far more grounded process called differential diagnosisoften shortened to DDx.

It’s not a dramatic “final answer” moment. It’s a practical list of the most likely (and the most dangerous) explanations for a symptom, ranked and refined until the truth has nowhere left to hide.

This article breaks down what differential diagnosis means, how it’s built, and why it mattersplus real, concrete examples that show the process in action.

(Quick note: this is educational, not personal medical advice. If you think you’re having an emergencylike severe chest pain, trouble breathing, fainting, or stroke symptomsseek urgent care.)

What Is a Differential Diagnosis (DDx), Exactly?

A differential diagnosis is a ranked list of possible conditions that could explain a person’s symptoms, based on the story (history), the exam,

and early test results. It’s used when symptoms don’t point to one clear causeor when several conditions can look similar at first glance.

Think of it like a responsible “shortlist,” not a doom-scroll. A DDx helps clinicians:

- Stay open-minded instead of locking onto the first idea.

- Rule out “can’t-miss” emergencies before focusing on common causes.

- Choose smart tests that separate look-alike conditions.

- Explain the plan to patients: “Here’s what we’re considering and why.”

Importantly, a differential diagnosis is not your final diagnosis. It’s the clinician’s best organized thinking before enough evidence exists to confirm one answer.

Why Differential Diagnosis Matters More Than You’d Think

Symptoms are surprisingly unoriginal. Chest pain, headache, fatigue, dizziness, coughthese can come from many different conditions, ranging from harmless to life-threatening.

Differential diagnosis exists because the body loves recycling the same “error messages” for completely different problems.

A good DDx protects patients from two common traps:

1) The “It’s Probably Nothing” Trap

Most symptoms are caused by common, non-dangerous issues. But a clinician still needs a structured way to make sure a rare-but-serious condition isn’t being missed.

In medicine, “rare” doesn’t mean “never,” and “probably” isn’t the same as “proven.”

2) The “It Must Be the Worst Thing” Trap

On the other end, anxiety can turn every symptom into a catastrophe. A differential diagnosis puts fear on a leash by ranking possibilities using evidence and patternsnot vibes and late-night internet searches.

How Clinicians Build a Differential Diagnosis

Different clinicians use different mental strategies, but most DDx building follows a similar flow:

Step 1: Define the Problem Clearly

This sounds basic, but it’s huge. “Chest pain” is not one thing. Is it sharp or pressure-like? With exertion or at rest? Seconds or hours? Associated with shortness of breath, fever, nausea, or anxiety?

The more precise the problem statement, the better the differential.

Step 2: Start Broad, Then Organize

Early on, clinicians often generate possibilities by pattern recognition (“This looks like X”) and by systematic thinking (“What categories could cause this?”).

To avoid missing options, many clinicians organize a DDx by:

- Body system (heart vs. lungs vs. GI vs. musculoskeletal vs. mental health)

- Anatomy (what structures live where the symptom is?)

- Time course (sudden vs. gradual; intermittent vs. constant)

- Triggers (food, exertion, position, stress, medications)

- Patient context (age, pregnancy status, chronic conditions, family history, exposures)

Step 3: Identify the “Can’t-Miss” Diagnoses

A key DDx skill is separating probable from dangerous. Some conditions are uncommon but serious enough that clinicians want to rule them out early.

This is why your clinician might ask intense questions about a symptom that seems “minor” to you: they’re checking for red flags.

Step 4: Rank the List (Likelihood + Risk)

Clinicians typically rank diagnoses using two axes:

- How likely is it? (based on commonness and how well it fits your story)

- How dangerous is it if we miss it? (even if less likely)

A well-ranked differential avoids two extremes: ordering every test for every possibility (expensive, stressful, sometimes harmful) or ordering too few tests and missing something critical.

Step 5: Test the HypothesesSmartly

Tests aren’t just to “find something.” They’re used strategically to separate similar conditions. A clinician chooses tests based on which result would actually change the plan.

Sometimes the best “test” is time and follow-upespecially when the most dangerous causes have been ruled out.

Tools Clinicians Use to Avoid Missing Something

Clinical Frameworks (a.k.a. “Mental Shelves”)

To keep the brain from forgetting an entire category, clinicians use frameworks. You might see mnemonics in medical training, but the point isn’t cute lettersit’s coverage.

Here are common categories used to organize differentials:

- Infectious (viral, bacterial, fungal)

- Inflammatory/Autoimmune

- Vascular (clots, bleeding, ischemia)

- Endocrine/Metabolic (thyroid, blood sugar, electrolytes)

- Medication/Toxin (side effects, interactions, withdrawal)

- Structural (stones, masses, injuries)

- Neurologic (migraine, stroke, neuropathy)

- Psychiatric/Functional (anxiety, panic, somatic symptom patternsafter medical causes are considered)

Checklists and “Debiasing” Questions

Humans love shortcuts. Unfortunately, so do diagnostic errors. Clinicians may use checklists or specific reflection questions to avoid cognitive traps like anchoring

(“I picked a diagnosis early and now everything looks like it”) or premature closure (“I found one answer, so I stopped thinking”).

The goal isn’t to make doctors roboticit’s to make sure the brain doesn’t quietly skip a crucial possibility on a busy day.

Differential Diagnosis Examples (Step-by-Step)

Let’s walk through some common symptoms and show what a differential can look like. These are examplesnot a way to self-diagnose.

Real clinicians use your full history, exam, and context.

Example 1: Chest Pain

Problem statement: “Tight chest pressure that worsens with exertion and improves with rest.”

A clinician might immediately consider categories: heart, lung, GI, muscle, anxiety. The first priority is ruling out dangerous causes.

Can’t-miss possibilities (not the full list):

- Heart-related ischemia (reduced blood flow to the heart)

- Pulmonary embolism (blood clot in the lung)

- Aortic problems (serious vessel issues)

- Pneumonia or other severe infection (depending on fever/cough)

More common possibilities (depending on details):

- GERD/acid reflux (burning, related to meals, worse lying down)

- Muscle strain/costochondritis (worse with movement or pressing on the chest wall)

- Anxiety/panic (often with palpitations, sweating, tingling, feeling of doomstill needs careful evaluation)

- Viral illness (especially with other cold symptoms)

How the DDx gets narrowed: history (exertion, risk factors), exam, EKG, and targeted labs/imaging if needed.

The aim is to quickly identify emergencies and then focus on the most likely cause.

Patient-friendly takeaway: chest pain has a wide differential, and that’s exactly why clinicians ask so many questions.

It’s not drama; it’s triage.

Example 2: Headache

Problem statement: “Throbbing headache with light sensitivity and nausea, recurring monthly.”

Likely possibilities:

- Migraine (common pattern with nausea/light sensitivity)

- Tension-type headache (pressure, band-like, often stress-related)

- Medication overuse headache (frequent pain-reliever use can backfire)

Red-flag possibilities clinicians watch for:

- Sudden “worst headache of life” (needs urgent evaluation)

- Fever + neck stiffness (possible infection around brain/spine)

- Neurologic deficits (weakness, confusion, vision loss)

- New headache after age 50 (different risk profile)

How the DDx gets narrowed: the pattern over time is powerful. A stable, repetitive pattern often points to primary headache disorders.

Sudden change in pattern, severity, or associated neurologic symptoms pushes clinicians toward urgent causes.

Example 3: Abdominal Pain (Right Upper Quadrant)

Problem statement: “Right upper belly pain after greasy meals, sometimes with nausea.”

Common possibilities:

- Gallbladder issues (pain after fatty meals; may radiate to back/shoulder)

- Acid-related disorders (upper abdominal burning, reflux symptoms)

- Liver inflammation (especially if jaundice or risk factors are present)

Can’t-miss or higher-risk possibilities (depending on symptoms):

- Gallbladder infection (persistent pain, fever)

- Pancreatitis (upper abdominal pain, worse after eating, sometimes severe)

- Appendicitis (pain can start vague and migrate; location varies)

How the DDx gets narrowed: timing (meals), exam findings, labs (liver/pancreas markers), and ultrasound if gallbladder disease is suspected.

Example 4: Fatigue

Problem statement: “Low energy for months, poor concentration, unrefreshing sleep.”

Common possibilities:

- Sleep issues (too little sleep, irregular schedule, sleep apnea)

- Stress, anxiety, or depression (often with appetite or sleep changes)

- Iron deficiency (with or without anemia)

- Thyroid disorders

- Medication side effects (including some allergy meds, mood meds, and others)

How the DDx gets narrowed: the “life context” matters a lotsleep, work/school stress, diet, activity, and mood.

Basic labs may be used to check for anemia, thyroid problems, and other common contributors.

How Tests Fit Into Differential Diagnosis (Without Turning You Into a Lab Report)

Tests are most useful when they answer a specific question, like:

“Is this infection?” “Is there inflammation?” “Is the heart under stress?” “Is there a clot risk?”

A helpful way to think about it:

- Some tests rule things out well (a normal result makes a condition much less likely).

- Some tests rule things in well (a positive result strongly supports a diagnosis).

- Many tests depend on timing (too early or too late can muddy results).

Good clinicians also avoid “testing as anxiety therapy.” More tests can sometimes lead to false alarms, unnecessary procedures, and extra stress.

Differential diagnosis helps keep testing purposeful.

Common Cognitive Pitfalls (and How Clinicians Try to Dodge Them)

Even experienced clinicians are human. The brain uses shortcutsgreat for crossing the street, less great for complex diagnosis.

Some classic pitfalls include:

- Anchoring: sticking to the first diagnosis even as new evidence appears.

- Availability bias: overthinking diagnoses that are “top of mind” (like a recent scary case).

- Premature closure: stopping the search once a plausible answer is found.

- Confirmation bias: noticing facts that support a favorite diagnosis and ignoring the rest.

Clinicians reduce these risks by using structured reflection, checklists, second opinions, and follow-up plansespecially when symptoms persist or change.

A strong differential diagnosis is less about being a genius and more about being methodical.

What Patients Can Do to Help the Differential Diagnosis Process

You don’t need a medical degree to be useful in your own diagnosis. You just need a clear timeline and details.

If you want to make your clinician quietly think, “Bless you,” try this:

- Describe timing: When did it start? Sudden or gradual? Constant or comes and goes?

- Describe triggers: Food, exercise, stress, position, time of day, menstrual cycle, new meds?

- Describe what changes it: Better with rest? Worse after meals? Improved by OTC meds?

- Bring a list: medications, supplements, allergies, and relevant family history.

- Share red flags: fainting, severe shortness of breath, weakness, confusion, high fever, blood in stool/urinedon’t bury the headline.

You can also ask smart questions that fit the DDx framework:

- “What are the top few possibilities you’re considering?”

- “What’s the most serious thing you want to rule out?”

- “What should make me seek urgent care?”

- “If symptoms don’t improve, what’s the next step?”

Key Takeaways

Differential diagnosis is the disciplined art of not jumping to conclusions. It’s a ranked, evolving list built from your story, exam findings, and targeted testing.

The process prioritizes safety (rule out dangerous causes), then probability (identify the most likely cause), while staying flexible as new information appears.

If you ever feel overwhelmed by uncertainty in medicine, remember: “We’re still working through the differential” doesn’t mean “we don’t know what we’re doing.”

It often means the clinician is doing exactly what they shouldthinking broadly, carefully, and safely.

Experiences Related to Differential Diagnosis ()

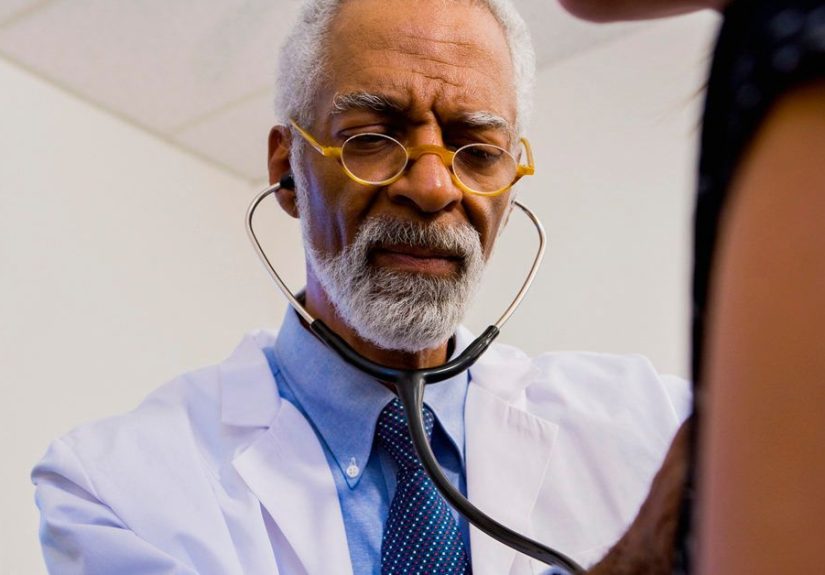

Differential diagnosis isn’t just a clinical methodit’s an experience. If you’ve ever sat on an exam table watching a clinician think, you’ve seen how DDx lives in the real world:

part detective work, part risk management, part communication challenge, and part emotional juggling act.

One common experience patients describe is the whiplash of hearing a “list.” When a clinician says, “Here are a few things this could be,” it can feel like someone just opened ten tabs in your brain

and every tab is named after a condition you definitely do not want to Google at 2 a.m. What helps is understanding the purpose of the list: it’s not a prediction of your future.

It’s a structured way to avoid missing the important stuff while working toward the simplest explanation that actually fits.

Clinicians, on the other hand, often experience DDx as a balancing act between speed and thoroughness. In urgent settings, the first job is safety:

rule out what could cause harm quickly. That’s why the questions can feel oddly intense (“Any crushing chest pressure? Any one-sided weakness? Any sudden worst headache?”) even when you came in for something that feels manageable.

Behind the scenes, clinicians are often running two mental checklists at once: “What’s most likely?” and “What’s most dangerous if I’m wrong?”

Another real-world experience is how much the story matters. Patients are sometimes surprised that a clinician spends time asking about timing, triggers, travel,

stress, sleep, medications, and family historybecause it can feel unrelated. But in DDx terms, those details are the “separators” that split one diagnosis from another.

“Pain after meals” nudges the list toward GI causes; “pain with exertion” raises concern for heart causes; “new symptom after starting a medication” can move side effects way up the ranking.

In many visits, a well-told timeline is more valuable than a random stack of unrelated tests.

Follow-up is also part of the experience. People sometimes think that if a clinician doesn’t name a final diagnosis immediately, something went wrong.

But many conditions reveal themselves over time. A strong DDx often comes with a plan: what to try now, what warning signs to watch for, and exactly when to recheck if things don’t improve.

That plan is the “safety net” of differential diagnosisbecause medicine isn’t always a single-visit puzzle with a neat ending.

Finally, there’s the emotional side. Uncertainty can be uncomfortable for patients, and cognitive overload can be real for cliniciansespecially in busy clinics or emergency departments.

The best DDx experiences tend to happen when both sides communicate: the patient shares clear details and concerns, and the clinician explains the reasoning in plain language.

When you hear, “Here’s what we’re considering, here’s why, and here’s what would change our plan,” that’s differential diagnosis doing its jobcalmly, carefully, and with your safety at the center.