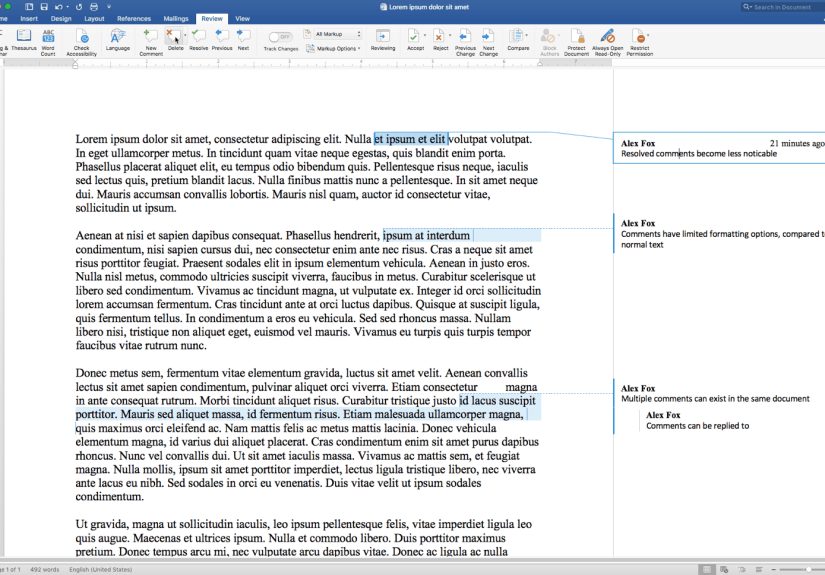

Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- The Discovery: “Hiding in Plain Sight” in Long Island Sound

- Meet the Defender: An Experimental Submarine With Wheels (Yes, Wheels)

- Simon Lake: The Inventor Who Wouldn’t Stop Rewriting the Future

- Why the Navy Didn’t Bite (Even When the Idea Was Clever)

- From Would-Be War Asset to Salvage Dream Machine

- The Amelia Earhart Moment: When a Submarine Became a Celebrity Backdrop

- How You Find a Lost Sub: Patience, Paperwork, and a Lot of Mapping

- Why This Matters: Defender Is a Time Capsule of American Innovation

- Preservation Questions: “Found” Is Only Step One

- Experiences at the End: What It Feels Like When History Comes Up Through the Fog (About )

Every so often, the ocean clears its throat and hands history backusually covered in silt, barnacles, and a century of

unanswered questions. That’s essentially what happened off the Connecticut coast when a team of divers identified what they

believe is the long-lost Defender, an experimental early-1900s submarine with a résumé so weird it sounds like it was

written by a committee of Jules Verne fans and practical engineers.

The story has everything: an inventor who wouldn’t take “no” for an answer, a submarine that could (in theory) roll along the

seabed on wheels, a diver “lock-out” hatch designed for underwater work, and a final act involving the U.S. Army Corps of

Engineers and a deliberate sinking that left the craft’s exact resting spot hazy for decades. Then, in April 2023, that hazy spot

became a real place again.

The Discovery: “Hiding in Plain Sight” in Long Island Sound

In mid-April 2023, a commercial-diving-led team located the wreck off the coast near Old Saybrook, Connecticut, more than 150

feet below the surface in Long Island Sound. Reports described challenging conditionstides, visibility, and the usual ocean

attitudebefore the group returned and confirmed they’d found a submarine-shaped time capsule on the bottom.

The most fascinating twist is that the wreck wasn’t necessarily “invisible” so much as “unidentified.” The area has been charted,

scanned, and sailed for generations. What changed wasn’t the oceanit was the research. By combining sonar and underwater

mapping surveys with historical digging (including public records work), the divers narrowed the search to an anomaly that matched

the submarine’s known dimensions and features. When they finally got eyes on it underwater, the pieces clicked.

And if you’re wondering whether the team immediately posted a pin on the internet for everyone to visitnope. The exact location

was kept quiet for a reason: once a wreck becomes famous, it can attract souvenir-hunters who treat history like a yard sale. In the

shipwreck world, “look but don’t touch” isn’t just a nice slogan; it’s how anything survives.

Meet the Defender: An Experimental Submarine With Wheels (Yes, Wheels)

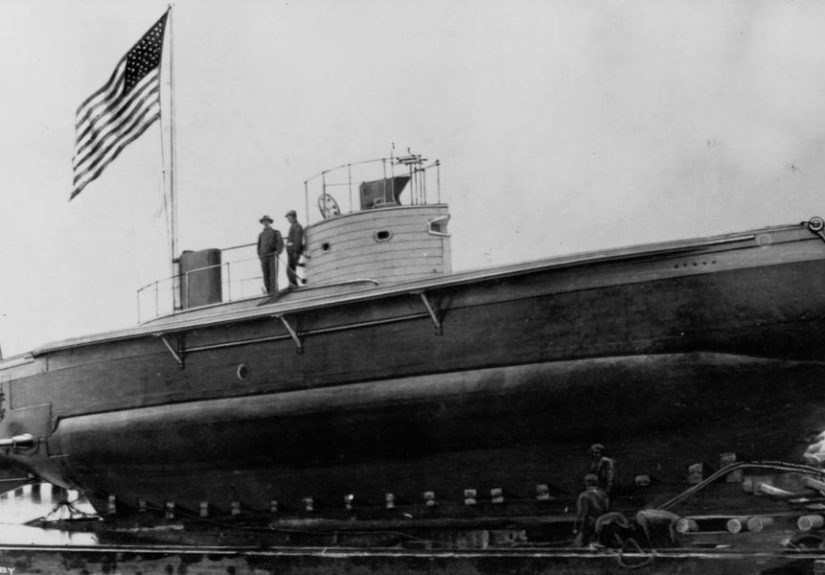

The Defender was built in the 1906–1907 era and originally carried a different nameoften cited as the Lake, connected to

its creator, Simon Lake, and his submarine-building ambitions. The design reflected an early-20th-century mindset: submarines

weren’t only weapons; they were also potential tools for salvage, rescue, and underwater labor.

The Defender’s most headline-friendly features were:

-

Seabed mobility concepts: a design that included wheels intended to help the craft move along the bottom under certain

conditions (a wild idea that makes more sense when you remember how much early submarine work overlapped with diving and salvage). -

A diver egress system: a bottom hatch arrangement meant to allow divers to exit the submarine underwater, turning the

vessel into a platform for underwater operations rather than a sealed “stay inside and hope” capsule. -

Multi-purpose ambitions: the Defender was pitched, adapted, and reimagined for different missionsminesweeping,

salvage, rescue workbecause its creator was determined to make it useful even if the Navy didn’t buy it.

In other words, Defender wasn’t just trying to be a submarine. It was trying to be a submarine plus: a work boat, a rescue

craft, a salvage tool, andwhen neededa persuasive sales brochure you could float.

Simon Lake: The Inventor Who Wouldn’t Stop Rewriting the Future

To understand why Defender existed, you have to meet the man behind it: Simon Lake, an American inventor and

submarine pioneer who spent decades chasing a vision of undersea travel and undersea work. Lake wasn’t the only person

building submarines in the late 1800s and early 1900s, but he was one of the most persistentand one of the most imaginative.

Lake built early submersibles such as the Argonaut series and pursued designs that emphasized stability, control, and

practical undersea capability. He also competed in a world where another major submarine figureJohn P. Hollandhad already

secured significant momentum with the U.S. Navy. That competition shaped everything: who got contracts, which designs became

standard, and which ideas stayed “almost famous.”

Even after setbacks, Lake kept going. Over time, he founded the Lake Torpedo Boat Company in Bridgeport,

Connecticut. Importantly, Lake’s story isn’t “inventor fails, curtain closes.” His company ultimately built submarines for the U.S. Navy,

and his influence shows up in the evolution of American undersea technologyeven when specific prototypes didn’t become

fleet staples.

Why the Navy Didn’t Bite (Even When the Idea Was Clever)

In the early submarine era, the U.S. Navy had to pick winners in a field where nearly everything felt risky. Submarines were still

proving they could be reliable, controllable, and useful in real-world conditions. In that environment, the Navy tended to favor

designs and builders with established track records, manufacturing capacity, and political-industrial momentum.

That meant some truly inventive concepts struggled to find a home. A “diver deployment hatch” is great if your mission is salvage

or rescue. A set of wheels for seabed travel is intriguing if you envision submarines as undersea work platforms. But navies often

buy for their mission priorities, not for what’s coolest in a workshop. And by the time Defender was in the mix, the U.S. Navy’s

submarine direction was already forming around other approaches and partners.

That doesn’t make Defender a failure. It makes Defender an example of something that happens constantly in technology:

innovation outruns procurement. A design can be brilliant and still lose the contract because timing, strategy, and

institutional preference matter as much as engineering.

From Would-Be War Asset to Salvage Dream Machine

When the Navy didn’t purchase the submarine, Lake did what determined inventors do: he kept modifying the pitch. Sources describe

the craft being refitted and repositioned for jobs like minesweeping, salvage, and rescue work. That’s where the name

Defender becomes especially fittingless “silent hunter” and more “underwater problem-solver.”

If you picture early-1900s salvage operationslimited communications, heavy gear, and a lot of hazardous guessworkit’s easier

to appreciate why an underwater-capable platform with diver support would have been tempting. Lake’s imagination extended to

big projects and big stunts, including schemes involving salvaging treasure from shipwrecks and supporting ambitious expeditions.

The Defender sat right in the middle of those dreams: a machine designed not merely to travel underwater, but to

do work underwater.

But invention isn’t the same thing as a business model. Even an ingenious vessel can struggle to find buyers, especially when

operating costs, maintenance, and market demand don’t line up. For long periods, Defender reportedly spent years unused or docked,

its story turning from “future of naval operations” to “local legend tied to a specific shoreline.”

The Amelia Earhart Moment: When a Submarine Became a Celebrity Backdrop

One of the most colorful footnotes in Defender’s history is its reported connection to Amelia Earhart, who visited the

vessel in 1929. Accounts describe Earhart being photographed in deep-sea diving gear connected to the Defender’s worldexactly

the kind of moment that turns a niche maritime prototype into a piece of pop history.

It’s a reminder that the early 20th century loved technological spectacle. Aviation pioneers, deep-sea divers, submarines, and

mechanical marvels shared the same cultural stage. People weren’t only interested in what these machines did; they were fascinated

by what these machines represented: progress with a side of daring.

That public fascination matters today because it helps explain why Defender wasn’t forgotten. Even when it wasn’t serving the Navy,

it remained a story people toldespecially along the Connecticut coast where Lake lived and worked, and where maritime history

is part of the local identity.

How You Find a Lost Sub: Patience, Paperwork, and a Lot of Mapping

Finding a wreck like Defender isn’t just a “jump in and hope” situationespecially at depths that demand serious training and

careful planning. Reports describing the search emphasize months of preparation: reviewing sonar and survey data, cross-checking

historical records, and looking for anomalies that match the vessel’s size and shape.

The “hiding in plain sight” line makes sense here. Long Island Sound is one of the busiest and most studied waterways on the U.S.

East Coast. The bottom has been scanned for navigation safety, construction planning, fisheries work, and other purposes. But a scan

doesn’t automatically assign a name. It takes someone who knows what they’re looking forand who cares enough to keep looking

after the first dozen leads go nowhere.

Once the dive team confirmed key features, the discovery shifted from “possible wreck” to “historic artifact.” And that’s where the

next phase begins: documentation, photography, careful measurement, andideallycollaboration with historians and preservation

experts who can help interpret what remains.

Why This Matters: Defender Is a Time Capsule of American Innovation

It’s easy to treat shipwreck stories like treasure hunts, but Defender’s real value is historical. It represents an experimental chapter

in American submarine development, a period when the “rules” of undersea warfare and undersea engineering were still being

written in pencil.

Defender also highlights a broader truth: technology evolves through paths not taken as much as through successes. When we

look back, we tend to draw a clean line from “first submarine” to “modern submarine,” as if progress happens in a straight march.

In reality, progress is a crowded room filled with prototypes, competitors, and brilliant ideas that arrived five minutes too early.

The submarine’s rediscovery also creates an opportunity to tell a fuller story about Simon Lake and the industrial ecosystem around

himConnecticut shipbuilding, early undersea experimentation, and the way inventors negotiated with the reality of military budgets

and contract politics. This is local history, national history, and technology history rolled into one steel hull.

Preservation Questions: “Found” Is Only Step One

Shipwrecks are fragile, even when they look tough. Saltwater corrosion is relentless, and the act of being “discovered” can put a wreck

at risk if people begin visiting it without care. That’s why teams often keep coordinates private, especially when a site is historically

significant and not yet formally protected.

In the best-case scenario, Defender’s story moves toward responsible stewardship: rigorous documentation, collaboration with

historical organizations, and a preservation approach that treats the wreck as a cultural resource rather than a scavenger hunt.

Sometimes that means leaving everything in place and collecting only images and measurements. Sometimes it involves legal

protections or formal recognition. Almost always, it means balancing curiosity with restraint.

Experiences at the End: What It Feels Like When History Comes Up Through the Fog (About )

Even if you’re not the one in the water, the “experience” of a discovery like Defender starts long before the splash. It begins with

the slow burn of research: late-night reading, old photos, half-reliable anecdotes, and maps that make you question whether north is

still north. There’s a special kind of suspense in searching for something you can’t seeespecially when the ocean has had a

century to rearrange the evidence.

On the day of a serious wreck dive, the mood on deck tends to swing between calm routine and bottled lightning. People check gear,

re-check gear, and then check the gear again because underwater, “oops” is not a strategy. The surface can look peacefuljust gray

water and a horizonwhile everyone knows the real world is down there, cold and dark and busy trying to swallow flashlights.

Reports about the Defender search described waiting on a buoy and watching conditions, including fog, while divers went down.

That waiting is its own kind of experience: a quiet stretch where time seems to thicken. Someone stares at the water a little too hard,

as if concentration alone can improve visibility. Someone else cracks a joke that isn’t really a joke. Then the boat goes quiet again,

because everyone’s mind is doing the same math: depth, current, minutes, gas, margins.

When the divers finally surface, the moment isn’t always dramatic in a movie way. It can be simpleeyes wide, voice slightly sharper

than normal, a quick confirmation that lands like a dropped anchor: “We found it.” And then the boat erupts, not because people love

yelling at the ocean, but because months (sometimes years) of effort have suddenly become real. The wreck stops being a story and

becomes a place.

There’s also a quieter emotion that hits afterward: respect. A vessel like Defender isn’t just “old metal.” It’s the physical record of

someone’s thinkingan inventor’s choices, compromises, ambitions, and stubborn hope. Seeing it on the bottom can feel like

meeting a historical figure in person, except the figure is 92 feet long and refuses to answer questions.

For local communities, discoveries like this can feel personal. Defender isn’t floating in the abstract ocean; it’s in the backyard of

Connecticut’s maritime storynear places where people worked in shipyards, launched experiments, and argued about the future over

coffee. For historians, it’s a chance to connect paper records with physical reality. For divers, it’s a reminder of why they chase

leads that sound ridiculous to everyone else: because sometimes the ridiculous lead is a submarine with wheels.

Final takeaway: The rediscovery of the Defender is thrilling not because it promises treasure, but because it returns a lost

chapter of American innovation to the conversation. It’s a story about persistenceLake’s persistence in building it, and modern

divers’ persistence in finding it. And it’s a story with a good moral: history doesn’t always sink quietly. Sometimes it waits, patiently,

for the right people to come looking.