Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- From Bombing Runs to Forecast Runs: Why the B-29 Was Perfect for Weather Work

- The Post-War Forecasting Problem: A Continent Downwind of a Mystery

- Meet the WB-29: Turning a Superfortress into a Flying Weather Laboratory

- The Arctic Missions: “Ptarmigan” Flights and the Quest for Upstream Data

- Storm Hunting: Hurricanes, Typhoons, and the Early Days of Aircraft Recon

- The Air Weather Service: Making Weather a Military Capability

- The Plot Twist: When “Weather Recon” Also Meant “Nuclear Recon”

- How These Flights Actually Improved Forecasts

- Legacy: From WB-29s to Today’s Weather and Hurricane Recon

- Conclusion: The Bomber That Became a Barometer

- Experiences: What It Would’ve Felt Like to Fly a WB-29 Weather Mission (About )

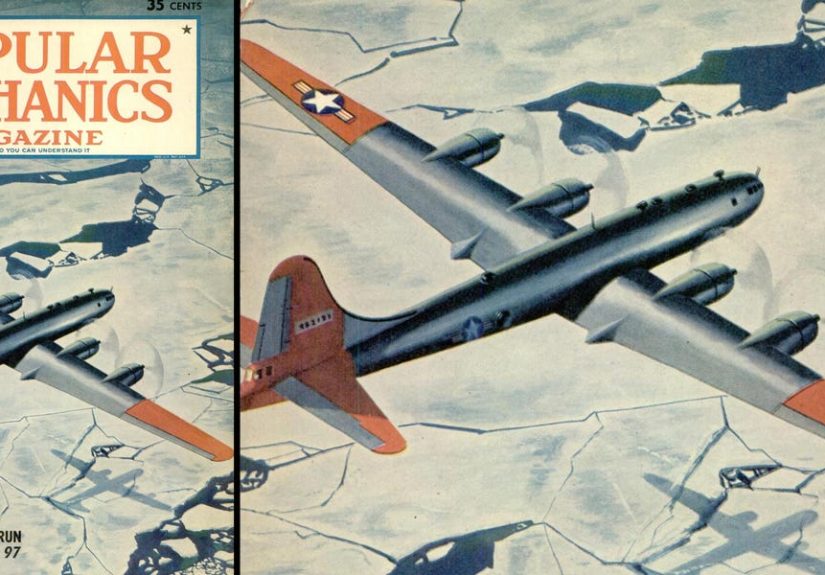

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress has one of the most dramatic résumés in aviation history. During World War II, it was

a high-altitude, long-range bomber built to end arguments from very far away. After the war, though, many B-29s

got reassigned to a quieter kind of power: helping the United States predict what the sky would do next.

That pivot wasn’t random, and it wasn’t charity work for meteorologists with clipboards. In the late 1940s, the

U.S. realized a simple truth: you can’t forecast North American weather well if you’re missing the “upstream”

atmosphereespecially the Arctic, where many cold outbreaks are born. The problem was that the Arctic (and much

of the open ocean) was basically a data desert. The solutionbecause aviation engineers never met a problem they

didn’t want to solve with horsepowerwas to fly a bomber into the blank spaces and make the atmosphere talk.

From Bombing Runs to Forecast Runs: Why the B-29 Was Perfect for Weather Work

Weather had already proven it could make or break operations during WWII. Long-range missions required solid

forecasting and reconnaissance, and military planners learned to treat clouds, winds, and icing the way they

treated fuel and flak: as mission-critical constraints. By war’s end, the U.S. had something meteorologists had

wanted for decadeslarge, fast, long-range aircraft that could reach remote regions reliably. Popular Mechanics

later described how postwar B-29 weather missions aimed at answering a question that mattered to everyone from

farmers to generals: what’s the weather going to do next week?

The B-29’s strengths made it a natural “flying weather lab.” It had range, payload capacity, and enough crew

stations to carry specialized operators and equipment. Most importantly, it could reach places other aircraft

struggled to touchlike far-north routes over ice-choked oceans. That mattered because, in the 1940s, there was

“practically no information” available north of about 70° latitude, and ground stations on the Arctic icecap were

unrealistic. Aircraft weren’t just helpful; they were the only practical option.

The Post-War Forecasting Problem: A Continent Downwind of a Mystery

Weather forecasting is basically detective work performed on a moving target. You observe what’s happening now,

infer where it’s headed, and warn people who may or may not listen. In the mid-20th century, forecasts leaned

heavily on surface observations from cities, ships, and a scattering of stationsthen meteorologists drew maps

by hand and tried to reason forward. It worked best when the observation network was dense.

The Arctic wasn’t dense. It was enormous, hostile, and (for forecasting purposes) inconveniently influential.

Air masses formed over the polar region could later surge south across Canada and into the United States. Without

upstream measurements, forecasters were trying to predict tomorrow’s chapter while missing half the book.

This is why the U.S. Air Force pushed hard into high-latitude weather reconnaissance. Unit histories describe how

the Air Force began probing weather in Alaska in 1946 and soon started dedicated over-the-pole flights to collect

data above the Arctic Circle.

Meet the WB-29: Turning a Superfortress into a Flying Weather Laboratory

Not every B-29 became a weather aircraft, but enough did to create a recognizable “weather variant” family.

Weather reconnaissance versions were commonly designated WB-29 (the “W” for weather). Hurricane and aircraft-recon

history references note that surplus WWII bombers gave weather reconnaissance a major boost, and that by 1950 the

B-29 had become the first aircraft to be designated with a “W” for weather service.

Converting a bomber into a weather platform meant trading offensive hardware for measurement hardware. Guns and

armor were less important than instrument racks, recording systems, radar, and the people trained to interpret

what the instruments were saying.

What did a WB-29 actually do onboard?

- Sample the atmosphere directly: temperature, pressure, humidity, winds aloft, and cloud structures.

- Track storms: locate centers, estimate movement, andwhen possiblemeasure central pressures.

- Report in real time: feed data back to forecast centers that could update maps and advisories.

- Fly where stations couldn’t exist: open ocean, polar routes, and remote regions with sparse reporting.

And yes, sometimes it did a “secret side quest,” which we’ll get tobecause apparently even weather missions can

come with plot twists.

The Arctic Missions: “Ptarmigan” Flights and the Quest for Upstream Data

If you want a mental image of these missions, picture a scheduled, long-duration flight from Alaska toward the

top of the worldhours and hours over cold water and ice, where “divert” is less a plan and more an inspirational

concept. Popular Mechanics described B-29s shuttling between Alaska and the North Pole on a regular timetable over

a track of roughly 3,290 nautical miles, laying foundations for long-range forecasting across North America.

Unit histories provide additional texture: the first Ptarmigan flight to the North Pole was flown in March 1947,

and later the path could be shortened after weather observer stations were established on an ice island known as

T-3.

In practical forecasting terms, these flights helped fill the “upstream” gap. If forecasters could observe

developing Arctic air masses earlierbefore they barreled southforecast confidence improved. Not perfect, not

magical, but measurably better than guessing based on a few sparse reports and hope.

Why the Arctic mattered so much

Many major winter patterns impacting the U.S. begin with polar air masses interacting with mid-latitude systems.

If you can measure the structure of cold air aloft and the winds steering it, you can anticipate timing and

intensity with more accuracy. The B-29’s range made that feasible when pre-war aircraft simply couldn’t reach

those areas reliably.

Storm Hunting: Hurricanes, Typhoons, and the Early Days of Aircraft Recon

While Arctic reconnaissance aimed at long-range pattern awareness, storm reconnaissance aimed at immediate danger.

Aircraft reconnaissance into tropical cyclones began earlier (WWII-era), and NOAA’s Hurricane Research Division

notes that the U.S. Navy and U.S. Air Force had been flying reconnaissance missions into tropical cyclones since

1944 to warn both civilians and military personnel.

In the Atlantic, historical reanalysis work on 1944–1953 hurricane seasons states that the Air Force operated

B-29 aircraft for hurricane reconnaissance beginning in 1946 and continuing beyond 1953.

These missions helped locate storm centers and, when conditions allowed, gather pressure data that could anchor

intensity estimates.

How did storm recon work in the 1940s and early 1950s?

It was part measurement, part navigation art, and part courage. Recon aircraft used instruments like pressure

altimeters and drift meters, and navigators often relied on dead reckoning to reach storms over open waterthen

refined position calculations more frequently as they approached the cyclone.

Dropsondes (expendable instruments dropped into a storm to measure pressure and other conditions) became more

regular in the Atlantic around 1950, adding another layer of datathough early dropsonde reports could be limited

compared with modern systems.

Meanwhile in the Pacific, units flying WB-29s became part of the typhoon reconnaissance story. Storm tracking in

that era could be rough, and early crews sometimes departed with only approximate storm positions, relying on

observations and experience to find the system.

The Air Weather Service: Making Weather a Military Capability

Weather reconnaissance didn’t happen in isolation. It sat inside a growing military weather enterprise. The U.S.

Air Force’s modern weather lineage traces back through World War I and formal organizational development during

WWII, with official lineage beginning in 1943 and evolving into what was known as the Air Weather Service.

That matters because the WB-29 story is not just “plane does science.” It’s “institution builds an operational

system” for collecting, distributing, and acting on environmental informationbecause airplanes, missiles,

shipping, and planning all live or die by the atmosphere’s mood swings.

The Plot Twist: When “Weather Recon” Also Meant “Nuclear Recon”

Here’s the part where the B-29’s post-war job description quietly grows another bullet point. Some WB-29 missions

didn’t just measure clouds and winds. They also collected atmospheric samples to detect radioactive debris from

nuclear tests.

In a 1949 milestone, a U.S. detection effort identified evidence connected to the first Soviet nuclear test.

The National Security Archive documents describe how “samples of air masses” collected in the Northern Pacific

showed abnormal radioactive contamination, and how a WB-29 flight on September 3, 1949 played a role in that

collection chain.

Air & Space Forces Magazine similarly recounts that after WWII, some B-29s became WB-29s used both for weather

reconnaissance and for “sniffing the air” for evidence of a Soviet nuclear detonationevidence found during a

September 3, 1949 flight with involvement from multiple U.S. government elements, including a secret Weather

Bureau Special Projects Section.

The “Bug Catcher” and the very literal meaning of air sampling

If you’re imagining a little jar on a string, think biggerand mounted to a bomber. A National Museum of the U.S.

Air Force photo description of a WB-29 from the 55th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron notes an air sampling scoop on

the aft upper fuselage, nicknamed the “Bug Catcher,” used to test radiation levels after surface nuclear weapon

tests (and the need for decontamination procedures afterward).

It’s a sobering reminder: the same aircraft type that helped forecast cold fronts also helped confirm a major

geopolitical shift. Weather reconnaissance, in the early Cold War, could be both public safety and national

intelligencesometimes on the same airframe.

How These Flights Actually Improved Forecasts

It’s easy to romanticize the WB-29 as a heroic flying lab (and okay, it kind of was). But the practical impact

came down to data: more measurements from more places, especially the places that “steered” weather into North

America.

1) Filling the Arctic and oceanic gaps

The Ptarmigan missions targeted the Arctic specifically because the region lacked routine observations and

traditional ground stations were infeasible.

Weather aircraft could measure conditions along a route, observe developing air masses, and feed that back into

forecasts downstream.

2) Better storm position and movement estimates

Early aircraft recon prioritized locating a storm’s center and tracking movement. Historical analysis emphasizes

that storm position fixes were the highest priority in the first decade of aircraft reconnaissance, because

accurate tracks underpin warnings and preparedness.

3) Pressure data that anchored intensity estimates

Central pressure was a powerful piece of storm intelligence in an era when wind estimates could be uncertain.

Aircraft reconnaissance increased the availability of pressure observations compared with the pre-recon era.

In other words: the WB-29 didn’t “solve weather.” It made weather less of a guessing game. And for forecasts,

reducing guesswork is basically the whole job.

Legacy: From WB-29s to Today’s Weather and Hurricane Recon

The WB-29 era sits at an inflection pointbetween a world of sparse observations and a world of satellites,

automated sensors, and high-resolution numerical models. Early aircraft reconnaissance was hazardous and often

depended on techniques that sound almost quaint today (dead reckoning, visual sea-state estimates, limited radar

capability).

Yet the core idea remains: if you want better forecasts, you need better observations, especially in the places

that drive your weather. Modern reconnaissance aircraft (and satellites) continue that mission with more precise

instruments, faster data transmission, and safer procedures. But the logicgo where the data isn’twas proven with

aircraft like the WB-29.

Even NOAA’s historical hurricane reconnaissance discussions show how aerial recon became a cornerstone of

understanding and forecasting storms, building from wartime-era experimentation into routine operations and later

research programs.

Conclusion: The Bomber That Became a Barometer

The B-29’s post-war weather mission is one of aviation’s best reinvention stories. A machine designed for

strategic bombing became a strategic observerpushing into the Arctic to map the birthplace of cold outbreaks,

tracking storms over open water, and feeding crucial data into a growing weather enterprise. Along the way, the

WB-29 also carried the weight of early Cold War intelligence, sampling the air for radioactive debris and helping

confirm a Soviet nuclear test.

If WWII turned the B-29 into an icon of industrial might, the post-war era turned some of those airframes into

something subtler: instruments of prediction. Not glamorous in the Hollywood senseunless you think cloud physics

is glamorous, in which case, welcome to the clubbut absolutely foundational to how modern weather forecasting

became a practical, operational capability.

Experiences: What It Would’ve Felt Like to Fly a WB-29 Weather Mission (About )

Imagine climbing into a Superfortress that’s been repurposed for weather work. The airframe still looks and feels

like a bomberbig, loud, and built with the kind of seriousness that suggests it was never meant to be “cute.”

But the mission vibe is different. Instead of bombs and targets, you’ve got instruments, notebooks, and a crew

whose job is to turn invisible air into numbers that matter.

The day starts early, because weather doesn’t care about your sleep schedule. In Alaska, the cold isn’t a

background detailit’s a co-worker that never stops talking. Preflight briefings feel equal parts science and

survival planning. You’re not just asking “Where are we going?” You’re asking “If something goes wrong, what

exactly counts as ‘somewhere else’ up here?”

Once you’re airborne, the mission becomes a rhythm: steady flight, constant checks, and a lot of patience. There

are long stretches where the horizon is mostly ice, ocean, and a sky that seems to go on forever. It’s oddly

monotonous and intensely alert at the same time. Someone is always watching engine gauges. Someone is always

recalculating position. Someone is always monitoring instruments and recording readings, because the whole point

is to bring home data from where there’s otherwise “practically no information.”

Then there are the moments that snap you awake. Turbulence doesn’t “shake the plane” so much as it reminds you

that the atmosphere is three-dimensional and occasionally cranky. Over storms, you can feel how quickly conditions

change. Early reconnaissance wasn’t always about dramatic eye penetrations; often it was about locating the

center and getting reliable fixes so forecasters could warn people in time.

Still, when you’re near a cyclone, the aircraft’s size doesn’t make you feel invincibleit makes you feel like a

very large object with a very large surface area for the wind to have opinions about.

The work itself is a mix of routine and revelation. A temperature reading here, a pressure measurement there, a

report transmitted back to base. It can sound boring on paper, but in the moment it feels like you’re pulling

back a curtain on a place humans can’t liveespecially over the polar routes. And every once in a while, you get

that quiet realization: these numbers will end up on a forecast chart that affects decisions thousands of miles

away.

There’s also the strange dual-purpose tension of the era. On some flights, “air sampling” might mean collecting

particulates for nuclear detectionfilters and scoops that crews nicknamed things like the “Bug Catcher.”

That’s a different kind of weight to carry. You’re still flying “weather,” but you’re also flying history, in a

world where the sky isn’t just weatherit’s evidence.

The landing is the part people think will feel triumphant. More often it feels like relief and fatigue. You’ve

been listening to engines, wind, and radio calls for hours. You’ve been staring at instruments and writing down

the atmosphere like it’s dictating a story. When the wheels touch down, the victory isn’t fireworks. It’s the

simple fact that you brought the data homebecause in that era, the data was the mission.