Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Before You Start: A 60-Second Checklist

- Method 1: Check Classic Log Files in /var/log (Tail + Less + Grep)

- Step 1: Find the Right Log File (Don’t Guess Forever)

- Step 2: Read the Most Recent Errors (Fast)

- Step 3: Follow the Log Live (Best for “It Happens When I Click This” Bugs)

- Step 4: Filter Noise with grep (Because Logs Love to Talk)

- Step 5: Don’t Forget Log Rotation (Yesterday’s Clue Might Be in a Compressed File)

- Example: Troubleshooting a 502/504 Error on Nginx

- Method 2: Use journalctl to Read systemd Logs (Targeted and Powerful)

- Quick Wins: The Most Useful journalctl Commands

- Filter by Service (The “Stop Reading Everything” Button)

- Filter by Time (Because “It Broke Sometime Today” Is Not a Timestamp)

- Filter by Severity (Show Me the Bad Stuff First)

- Common “Make It Readable” Options

- Example: A Service Won’t Start After a Config Change

- Bonus: Use PuTTY to Save What You See (So You Don’t Lose the Smoking Gun)

- Troubleshooting Cheat Sheet: What Errors Usually Mean

- Conclusion

- Real-World Experiences and Lessons (Extra 500+ Words)

If you’ve ever stared at a server that’s misbehaving while your coffee gets cold, welcome to the club.

The good news: most server problems leave footprints. The better news: you can follow those footprints

from your Windows PC using PuTTY.

PuTTY itself doesn’t “store” your server logsit’s the tool that gets you into the server (usually over SSH),

so you can read the logs where they actually live. This guide walks you through two simple, reliable methods:

(1) checking classic log files (like /var/log/syslog) and (2) using journalctl for systemd logs.

Before You Start: A 60-Second Checklist

- Have SSH access: You’ll connect in PuTTY using your server IP/hostname and SSH port (typically 22).

- Know your permission level: Many logs require

sudo. If you see “Permission denied,” that’s normalusesudo(if allowed). - Know your distro (roughly): Ubuntu/Debian commonly use

/var/log/syslog; RHEL/CentOS often use/var/log/messages. - Confirm time: Logs are timestamped. Run

dateso you don’t chase the wrong time window.

Method 1: Check Classic Log Files in /var/log (Tail + Less + Grep)

This is the “open the notebook and read the last few pages” method. Most Linux systems keep many

human-readable log files under /var/log. Your job is to (a) pick the right file and (b) zoom in on the right lines.

Step 1: Find the Right Log File (Don’t Guess Forever)

Start by seeing what’s available:

Common system logs (varies by distro):

- General system activity:

/var/log/syslog(common on Ubuntu/Debian) or/var/log/messages(common on RHEL/CentOS) - Authentication / SSH / sudo:

/var/log/auth.log(Ubuntu/Debian) or/var/log/secure(RHEL/CentOS) - Kernel messages: sometimes

/var/log/kern.log(Ubuntu/Debian) and also available viadmesgorjournalctl -k

Common web/app logs (if you’re troubleshooting a site):

- Nginx: often

/var/log/nginx/error.logand/var/log/nginx/access.log - Apache: often

/var/log/apache2/error.log(Debian/Ubuntu) or/var/log/httpd/error_log(RHEL/CentOS)

If you’re not sure where an app logs errors, check its config. For example, Nginx uses directives like

error_log; Apache uses ErrorLog. A quick “find the setting” approach:

Step 2: Read the Most Recent Errors (Fast)

Most of the time, the newest messages matter most. Use tail to read the last lines of a log without loading the whole file.

Want to browse comfortably? Use less, which lets you scroll and search.

Tip: in less, press Shift+G to jump to the end (where the newest entries are).

Useful inside less:

/errorthen Enter to search for “error”nfor next match,Nfor previous matchShift+Gto jump to the bottomqto quit

Step 3: Follow the Log Live (Best for “It Happens When I Click This” Bugs)

If the error happens when you refresh a page, run a cron job, or restart a service, “live tailing” is your best friend.

For web servers, tail the actual app error log while you reproduce the problem:

Step 4: Filter Noise with grep (Because Logs Love to Talk)

Logs are chatty. grep helps you extract the lines that matter. Combine it with tail to focus on recent entries.

If you need to follow live output but only for a specific service or keyword:

Step 5: Don’t Forget Log Rotation (Yesterday’s Clue Might Be in a Compressed File)

Many systems rotate logs: older logs become .1, .2.gz, and so on.

If the problem happened “last night,” your evidence may have already moved.

Example: Troubleshooting a 502/504 Error on Nginx

Scenario: your site returns 502 Bad Gateway or 504 Gateway Timeout.

Those are often reverse-proxy symptomsNginx couldn’t talk nicely to the upstream app (PHP-FPM, Node, Gunicorn, etc.).

-

Tail the Nginx error log and reproduce the error:

-

Look for clues like:

connect() failed (111: Connection refused)(upstream not running or wrong port)upstream timed out(app too slow or overloaded)permission denied(file/socket permission problem)

-

Then check the upstream service logs (often via

journalctlin Method 2 below), or the app’s own log file if it has one.

Method 2: Use journalctl to Read systemd Logs (Targeted and Powerful)

On many modern Linux distros, services managed by systemd also write to the system journal (handled by systemd-journald).

Instead of hunting through multiple files, journalctl lets you query logs by service, time window, boot session, and severity.

Quick Wins: The Most Useful journalctl Commands

Filter by Service (The “Stop Reading Everything” Button)

If a specific service is failing (Nginx, Apache, SSH, Docker, etc.), filter by unit name:

Not sure of the exact unit name? Find it:

Filter by Time (Because “It Broke Sometime Today” Is Not a Timestamp)

Time filters turn a scrolling novel into a short story. Use --since and --until:

Filter by Severity (Show Me the Bad Stuff First)

If you only want errors (or worse), filter by priority:

Common “Make It Readable” Options

If output is long or you’re pasting into a ticket, these help:

Example: A Service Won’t Start After a Config Change

Scenario: You updated a config file, restarted the service, and it failed. Classic.

Here’s a clean workflow in PuTTY:

-

Check status first (gives a hint and the unit name):

-

Pull the service logs around the failure:

-

If you restarted “just now,” use a time window:

-

Fix the config, restart, and follow live logs during the restart:

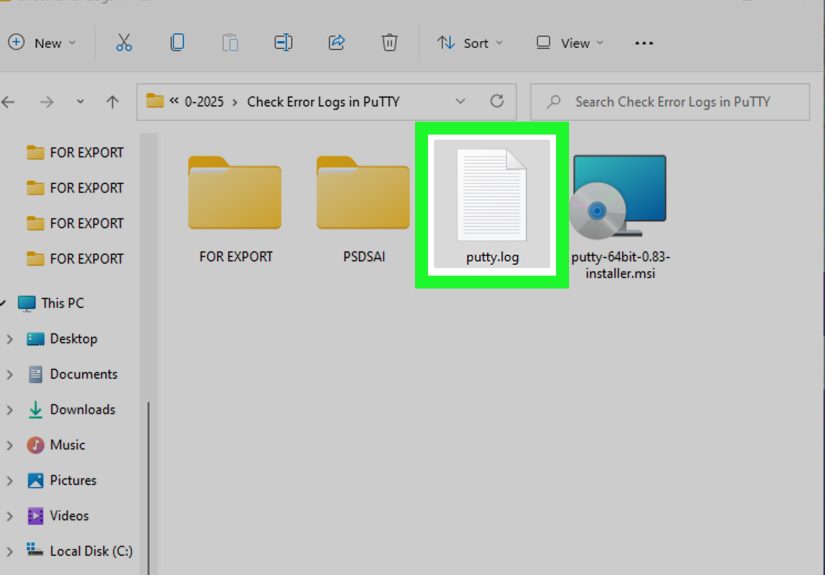

Bonus: Use PuTTY to Save What You See (So You Don’t Lose the Smoking Gun)

Sometimes you need to attach evidence to a support ticket or share it with a teammate.

PuTTY can log your session output to a local file from its Logging settings.

Use this carefullylogs may contain usernames, IPs, file paths, and other sensitive details.

- Enable PuTTY session logging (choose a log file name and a logging mode such as “Printable output” or “All session output”).

- Consider “Printable output” if you want something easy to read.

- Don’t leave logging on forever; you’ll fill your disk and your future self will be mad at you.

Troubleshooting Cheat Sheet: What Errors Usually Mean

- Permission denied: wrong file permissions, SELinux/AppArmor, or you’re not using

sudo. - Connection refused: the upstream service is down or listening on a different port/socket.

- Timed out: app is too slow, overloaded, or blocked on external calls (DB, API, DNS).

- No space left on device: disk full (and yes, logging might be part of the reason).

- Segmentation fault: a crashoften needs package/service investigation, and sometimes a core dump.

- Authentication failure: wrong keys/passwords, disabled login method, or brute-force attempts.

Conclusion

When you’re checking error logs using PuTTY, the winning move is choosing the right “lens.”

If you’re working with classic log files and app-specific logs, go with Method 1:

tail, less, grep, and the files in /var/log.

If your system uses systemd (most modern distros do) and you want targeted, service-based searching,

Method 2 with journalctl is faster and often cleaner.

Either way, your server is probably already telling you what’s wrong. You just have to read its diary.

(Servers have feelings too. Mostly about permissions.)

Real-World Experiences and Lessons (Extra 500+ Words)

The “how” is easy once you know the commands. The “what does this mean at 2:13 AM” part is where real life shows up.

Here are a few realistic scenarios you’ll run into when checking error logs using PuTTY, along with the kinds of lessons

that stick (because you only learn them the hard way once).

1) The Case of the Missing Log File

You SSH in, confidently run tail -f /var/log/nginx/error.log, and… nothing. Or worse: “No such file or directory.”

Your first instinct might be panic. Your second instinct should be: “Where does this installation log?”

Different distros, containers, and custom installs change paths. Sometimes Nginx logs to a nonstandard location,

or logs to stderr under a process manager. The fix is usually boring and effective:

check the config for the error_log directive, or use systemctl status nginx and

journalctl -u nginx.service. The lesson: don’t treat log paths like universal laws of physics.

Treat them like “defaults,” and verify.

2) “It Only Happens Sometimes” (a.k.a. The Timeout Mirage)

Intermittent bugs are where live tailing becomes your superpower. A common pattern: users complain about slow loads,

and the site occasionally returns a 504 timeout. If you only read the last 50 lines of a log after the fact,

you might miss it. But if you tail the error log live while reproducing the issuerefresh the page, run the job,

hit the endpointyou’ll catch messages like “upstream timed out,” “connection reset,” or “worker process exited.”

The lesson: when a bug is timing-dependent, your troubleshooting should be real-time too.

3) Log Rotation: The “Where Did Last Night Go?” Problem

Another classic: you’re asked to investigate an error from “yesterday,” and today’s log looks clean.

That’s usually log rotation at work. Syslog and app logs often roll over daily or when they hit a size limit.

Yesterday’s evidence may be sitting in syslog.1 or syslog.2.gz.

The first time you discover zless and zgrep, it feels like unlocking a secret door.

The lesson: if the timeline doesn’t match what you see, check rotated and compressed logs before you declare victory.

4) The Permission Denied Red Herring

In PuTTY, it’s easy to assume “Permission denied” means the server is broken. Often it just means you’re reading

a privileged file as an unprivileged user. You try to open /var/log/auth.log and get blocked, so you

conclude the log is “gone.” It’s not goneyou’re just not invited. Using sudo (when permitted) fixes it,

but the deeper lesson is operational: if you don’t have the access you need, your troubleshooting will be partial.

The best habit is to notice permission issues early and either switch to an authorized account or request the access

you need, rather than spending an hour “debugging” an access control policy.

5) Journald vs. File Logs: The “Two Truths” Trap

Sometimes you’ll find different clues in different places. For example, an app might write its own detailed errors

to /var/log/myapp/error.log but systemd will record the startup failures (and restart attempts) in the journal.

Or you’ll see Nginx complain in /var/log/nginx/error.log, while journalctl -u php-fpm reveals

that PHP-FPM is crashing due to a configuration typo. Both are true; they’re just telling different parts of the story.

The lesson: logs are like witnesseseach has perspective. Use Method 1 for file-based detail, Method 2 for service-level

context, and combine them when the root cause hides between the layers.

6) The Timestamp and Time Zone Facepalm

One of the most common “experienced” mistakes is searching the wrong time window. Your monitoring alert might be in UTC,

but your server logs might be in local time, or vice versa. Or you filtered journalctl --since "today" and forgot

that “today” is based on the server’s clock, not yours. A quick date at the start saves a lot of confusion.

The lesson: before you interpret an event, confirm what “now” means on that system.

Put all of these together and you get a practical truth: checking logs is not just about commandsit’s about habits.

Verify locations, watch live when the bug is live, respect rotation, use the journal for service context, and always

sanity-check timestamps. Do that, and PuTTY becomes less of a panic portal and more of a calm, methodical flashlight.