Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What “Abstract” Means When Your Shutter Stays Open

- The Core Recipe: Slow Shutter + Intent + Control

- Five Long-Exposure Paths to Abstraction

- My Simple Field Workflow (So I Don’t Guess Forever)

- Troubleshooting: The Stuff That Tries to Ruin Your Art

- Editing Long Exposure Abstracts Without Killing the Magic

- Conclusion: Make Time Your Paint

- My 500-Word Long-Exposure Diary: What I Learned From Chasing Blur

I used to think photography was about freezing a moment. Then I discovered long exposure, and realized I’d been living a lie.

With a slow shutter, you don’t freeze timeyou melt it down, pour it into the frame, and let it cool into something strange and beautiful.

Water turns to silk. Clouds become brushstrokes. City lights write neon calligraphy. And people? People become polite ghosts who never ask you to retake the photo.

If you’ve ever looked at an abstract long exposure and thought, “Is that… art or did their camera sneeze?”good news: it can be both.

In this guide, I’ll walk you through how I intentionally create abstract images with long exposure photography, from gear and settings to creative techniques,

plus the hard-earned lessons you only learn after you’ve accidentally made 47 blurry disasters in a row.

What “Abstract” Means When Your Shutter Stays Open

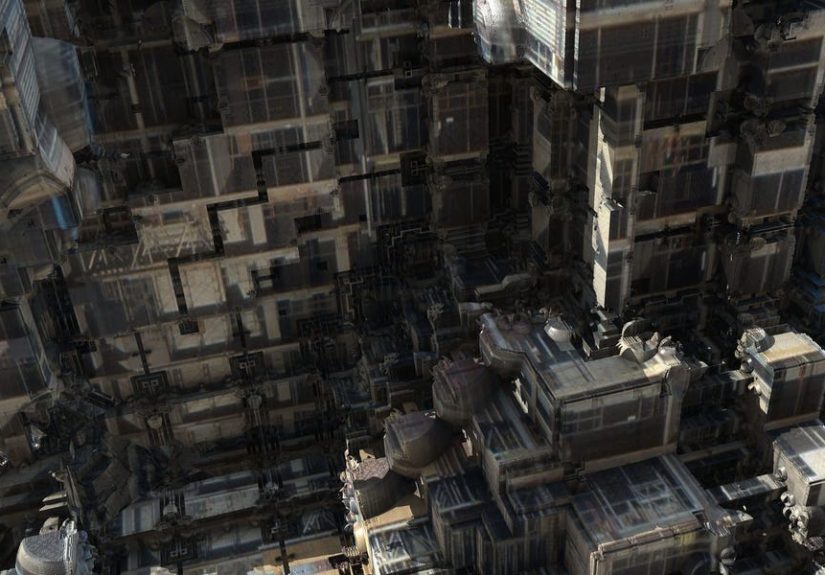

Abstract photography isn’t “random.” It’s when you remove (or reduce) literal reality so the viewer notices shape, color, texture, rhythm, and motion first.

Long exposure is a shortcut to abstraction because it records movement over time. Instead of a single instant, your camera collects a small timeline and

compresses it into one image.

Think of your sensor like a notebook. At fast shutter speeds, it writes one word. At slow shutter speeds, it writes a whole paragraphsometimes a poem,

sometimes a grocery list, sometimes a dramatic monologue delivered by streetlights.

Why long exposure is such an “abstract-friendly” tool

- Motion becomes form: car headlights become lines, waves become mist, branches become soft texture.

- Time simplifies clutter: moving crowds thin out; busy water surfaces smooth over; chaos turns calm.

- You control the “translation”: by choosing shutter speed and how (or whether) the camera moves, you decide how reality gets rewritten.

The Core Recipe: Slow Shutter + Intent + Control

Great abstract long exposures don’t happen because you set your camera to “whatever” and hope the universe is feeling generous.

They happen when you build a repeatable base and then experiment on top of it.

1) Shutter speed: your main creative dial

Shutter speed decides how much time gets poured into the frame. There’s no universal best setting, but these ranges are a useful map:

- 1/30 to 1/4 sec: subtle blur, painterly edges, great for early ICM (Intentional Camera Movement).

- 1/2 to 2 sec: obvious motion streaking; ideal for handheld ICM practice and gentle subject movement.

- 5 to 30 sec: classic light trails, flowing water “silk,” clouds starting to stretch.

- 30 sec to minutes (Bulb mode): dramatic cloud bands, ultra-smooth water, minimalist seascapes, and “where did the people go?” scenes.

Many cameras top out at 30 seconds before you need Bulb mode for longer exposures. If you’re going Bulb, a remote release or interval timer

makes life easierand keeps your fingerprints out of the process.

2) Exposure triangle for long exposure abstracts

For most long exposure work, I start with:

- ISO: low (often 100) to keep noise and hot pixels from throwing a confetti party.

- Aperture: mid-range (often f/8–f/11) for sharpnessunless I’m intentionally leaning into softness for the abstract look.

- Shutter speed: chosen for the effect, then supported by ISO/aperture and filters.

For ICM, I’m less precious about razor sharpness. In fact, a little softness can be part of the vibe. But I still aim for clean tones and controlled highlights,

because blown highlights are the visual equivalent of someone yelling during a quiet piano recital.

3) ND filters: sunglasses for your camera

If it’s bright outside, long exposures require cutting light. That’s where neutral density (ND) filters come in.

A solid ND filter reduces light without (ideally) changing color, letting you use slower shutter speeds in daylight.

A few practical notes from the field:

- 3-stop ND: helpful for mild slowing (waves, waterfalls in shade).

- 6-stop ND: a workhorse for visible smoothing in daylight.

- 10-stop ND: the “turn noon into night” classic for 30-second to multi-minute exposures.

- Variable ND: convenient, but can introduce artifacts or unevenness at extremestest before a “once-in-a-lifetime” location.

I often meter without the filter, then use a long exposure calculator (or a mental shortcut) to convert the shutter speed once the ND is on.

With practice, you get a feel for itlike knowing how spicy “medium” is at your favorite taco place.

4) Stability: the boring part that makes the fun part possible

Long exposures are allergic to vibration. My stability checklist:

- Tripod (sturdy beats tall and flimsy).

- Remote release or 2-second timer to avoid shutter-jab shake.

- Turn off stabilization when locked down on a tripod (some systems hunt when they shouldn’t).

- Shield from wind (your body can be a windbreak; your camera bag can add weight).

5) Focus: do it before the world gets dark

When using strong ND filters, autofocus can struggle. I typically focus first (without the filter if needed), then switch to manual focus

so the camera doesn’t “help” me into a soft image at the last second.

Safety note (because cameras are expensive)

For very long exposuresespecially in Bulbavoid aiming at intense light sources like the sun.

Long exposure + direct sun can cause heat and damage. If you’re experimenting with daytime abstracts, choose safer subjects (water, clouds, architecture),

and use proper filters and technique.

Five Long-Exposure Paths to Abstraction

1) Intentional Camera Movement (ICM): painting with the camera

ICM is exactly what it sounds like: you move the camera during the exposure on purpose. It’s rebellious, expressive, and occasionally humiliating.

The first 20 attempts often look like a toddler shook your camera while yelling, “ART!”

Here are ICM moves I actually use:

- Vertical drag: perfect for trees, reeds, tall buildings. Pull down smoothly during exposure to create painterly streaks.

- Horizontal sweep: great for horizons, city blocks, shoreline lines.

- Rotation: spin around a central point for whirlpool energy (works well with bright highlights).

- Zoom burst: zoom in/out during exposure for starburst lines (best with lights or high-contrast shapes).

- Micro-jitters: tiny controlled movements for a softer “dream” blur rather than obvious streaks.

Starting settings I recommend:

- Shutter: 1/10 to 1 sec to start; go longer if you want heavier abstraction.

- ISO: low.

- Aperture: f/8-ish, then adjust for light and look.

The secret sauce is rhythm. Smooth motion looks intentional. Jerky motion looks like regret.

I practice the movement before pressing the shutterlike rehearsing a dance move I definitely can’t do at weddings.

2) Light trails: letting the city write for you

Light trails are long exposure’s gateway drug. They’re dramatic, forgiving, and instantly recognizable.

Then, once you get bored (it happens), you can push them toward abstraction by changing your angle, adding camera movement,

or framing only the trails so the scene becomes pure line and color.

My go-to approach:

- Shoot at dusk or night when ambient light is manageable.

- Use a tripod and start around 5–15 seconds.

- Watch highlightsheadlights can blow out fast.

- Try a zoom burst or a gentle rotation mid-exposure for abstract “light ribbons.”

Locations that deliver:

- Overpasses and curved roads (lines naturally lead the eye).

- Ferris wheels and amusement parks (circles + repetition = instant abstract design).

- City intersections with mixed light sources (warm sodium + cool LED = color contrast).

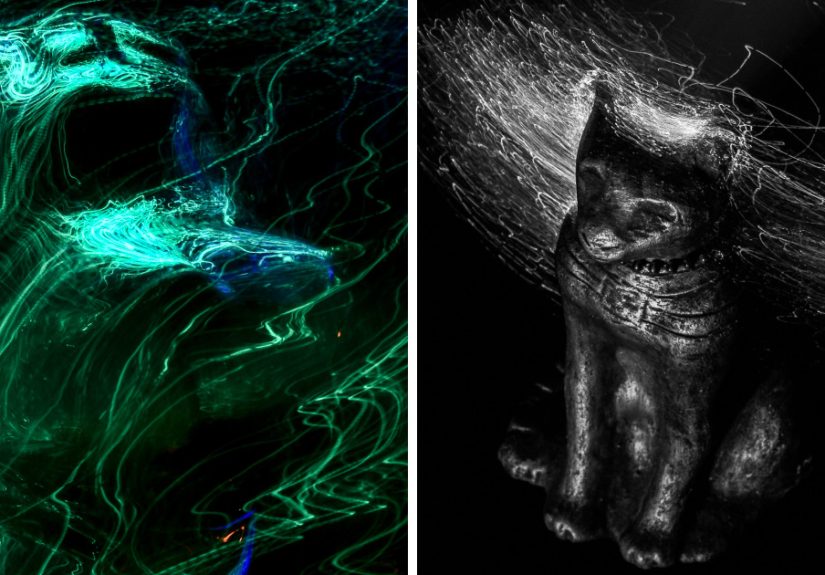

3) Light painting: drawing in midair

Light painting is where long exposure becomes performance art. You open the shutter, then “paint” with a flashlight, LED wand, or even your phone screen.

It’s equal parts technique and improv comedybecause sometimes you trip over your own feet and invent a new style called “panic scribble.”

Practical starting point:

- Shutter: 2–10 seconds for simple experiments; longer if you need more time to paint.

- ISO: low.

- Aperture: mid-range to control brightness and depth.

- Tip: keep moving so you don’t appear in the frame, or embrace the ghost effect on purpose.

Abstract idea: paint only texturesshort strokes on walls, rocks, treesso the subject becomes a glowing pattern rather than “a thing.”

4) Water and clouds: nature’s built-in blur brush

Flowing water and moving clouds are long exposure royalty. They’re reliable, beautiful, and they naturally simplify complicated scenes.

Want abstract? Crop tighter. Focus on the direction of motion. Let the subject be texture instead of location.

A few specific examples I’ve used:

- Waterfall close-up: frame just the falling water and rock edges; use 1/2–2 seconds for “silk,” longer for “fog.”

- Seascape minimalism: 30 seconds to 2 minutes turns choppy waves into a smooth gradientsky and water become two calm color fields.

- Fast clouds over a fixed landmark: multi-minute exposures create dramatic streaks that feel like charcoal shading across the sky.

If you want a more painterly feel, combine this with subtle ICMlike a gentle vertical drag on a shoreline scene.

Suddenly the ocean looks like a canvas and the horizon looks like a decision you made on purpose.

5) People into ghosts: abstracting motion in human spaces

Busy public places can become abstract patterns with the right exposure. With a tripod and a slow shutter, moving people fade while static architecture stays put.

The result can be eerie, calm, or graphic depending on how you frame it.

- Museum or station: 1–5 seconds can turn foot traffic into soft streaks.

- Crosswalk at night: mix ghosted pedestrians with light trails for layered motion.

- Abstract strategy: crop out faces and signs; keep only silhouettes, repetition, and light.

My Simple Field Workflow (So I Don’t Guess Forever)

- Pre-visualize the motion: What’s moving? In what direction? How do I want it to lookstreaks, haze, ribbons, or pure color?

- Lock composition: tripod planted, horizon leveled (unless I’m intentionally breaking that rule).

- Focus first: especially if using a strong ND filter.

- Meter without ND: get a baseline exposure.

- Add ND + calculate: convert shutter speed based on ND strength.

- Shoot a test: check histogram and highlights, adjust, repeat.

- Experiment: change shutter speed, add slight movement, try zoom burstone variable at a time.

The key is to separate “technical correctness” from “creative exploration.”

I get the exposure stable first, then I start doing weird stuff on purpose.

Troubleshooting: The Stuff That Tries to Ruin Your Art

Problem: Blown highlights that look like tiny suns

Fix: shorten exposure, stop down aperture, lower ISO, or reduce ambient light (shoot later). In abstract work, highlights can be gorgeousbut only if they’re controlled.

If they’re pure white blobs, they stop being “sparkle” and start being “broken.”

Problem: Weird color casts with strong ND filters

Fix: shoot RAW, set a custom white balance if needed, and learn your filter’s personality. Some heavy NDs lean warm or cool.

If the cast supports your abstract palette, keep it. If it looks sickly, correct it in post.

Problem: Hot pixels and noisy shadows in long exposures

Fix: keep ISO low, avoid overheating the sensor with repeated multi-minute shots, and consider your camera’s long-exposure noise reduction option.

Some cameras use “dark frame subtraction,” which can reduce hot pixels but may double the time per shot (because it captures an extra dark frame).

Problem: Micro-shake from wind, bridges, or your own impatience

Fix: stabilize the tripod, use a timer/remote, and avoid extending the center column. If the ground vibrates (bridges, boardwalks),

time your exposure between foot traffic or move to a more solid surface.

Problem: Everything looks mushy, not dreamy

Fix: confirm focus, avoid extreme apertures that soften detail, clean your filter, and check for motion you didn’t intend (branches, grasses, hanging straps).

“Dreamy” is intentional. “Mushy” is usually a technical problem wearing a trench coat.

Editing Long Exposure Abstracts Without Killing the Magic

My goal in editing is simple: preserve the feeling of motion while clarifying the design. I’m not trying to “fix” the abstract.

I’m trying to help it communicate.

- Start with white balance: make the color mood deliberate.

- Control highlights: keep luminous areas textured when possible.

- Shape contrast: use curves or tone sliders to emphasize flow and direction.

- Remove distractions: a random bright dot can hijack the whole composition.

- Crop like a designer: abstraction often improves when you remove context and leave only form.

If you want a signature style, build it around one consistent choice: a recurring shutter-speed range, a repeating motion gesture (like vertical drags),

or a color palette you lean into. Style is just consistency with confidence.

Conclusion: Make Time Your Paint

Long exposure photography is a strange kind of honesty. It shows what your eyes can’t hold onto: movement, rhythm, passing time.

And when you push it toward abstractionthrough ICM, light trails, light painting, or minimalist motionyou’re not documenting a place.

You’re translating an experience.

Start with control. Add one creative variable. Repeat until you accidentally make something you lovethen learn how to do it again on purpose.

That’s the whole game.

My 500-Word Long-Exposure Diary: What I Learned From Chasing Blur

The first time I tried to create abstract images with long exposure photography, I brought a tripod, a 10-stop ND filter, and a heroic amount of optimism.

I also brought exactly zero patience, which is a bold choice for a technique where your camera literally takes its time.

My first shot was a two-minute exposure of a beach. I stared at the blinking timer like it owed me money. When it finished,

the preview looked like a gray soup with a horizon line that felt emotionally uncertain.

But here’s what surprised me: even the “bad” frames had something in theman interesting streak, a strange gradient, a texture that felt like a painting.

So I stopped trying to force the scene to look like the examples I’d seen online. Instead, I started asking a different question:

“What does this place do when time is stretched?” That mindset shift changed everything.

I learned to treat shutter speed like a paint thickness. A half-second is watercolorlight, transparent, delicate.

Ten seconds is acrylicbold strokes, obvious motion, strong shape changes.

Two minutes is oil paintsmooth blending, quiet transitions, the kind of calm that makes you wonder if the ocean is secretly meditating.

Once I saw shutter speed as a creative material, not just a technical setting, my images became less accidental and more authored.

I also learned that ICM is basically choreography. If I moved the camera like I was swatting a mosquito, I got chaos.

If I moved it like I was drawing a line with a pencilsteady, deliberate, rehearsedI got structure. I began practicing movements before shooting:

a gentle vertical pull for trees, a slow rotation for streetlights, a careful zoom burst for neon signs.

The weird part is how physical it became. My best ICM sessions felt like I’d done a tiny workout, except the gym was a forest and my dumbbells were photons.

And then there’s the emotional lesson: long exposure punishes impatience but rewards curiosity. When I stopped chasing “perfect”

and started chasing “interesting,” the work got better fast. I began making series instead of one-off lucky shots:

ten variations of the same scene with different shutter speeds, five different camera movements with the same subject,

three exposures where I only changed where the brightest highlights sat in the frame. Patterns appeared. Preferences emerged.

That’s where personal style quietly shows upwhile you’re busy experimenting.

Today, I still delete plenty of frames. But I don’t feel defeated by them. Each miss tells me something specific:

“Too much movement.” “Not enough time.” “Highlights need a different position.” “This would sing with a slower sweep.”

Long exposure abstracts taught me to iterate on purpose. And honestly? That’s a pretty great life skill for everything else, too.