Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why Amateur Bird Paintings Hit Us Right in the Feelings

- The Secret Sauce: What Amateur Painters Do to Birds (On Purpose or Not)

- Borrow This From Birdwatchers: A Friendly “Field Mark” Mindset for Artists

- How I Built My Tribute Series: Keeping the Charm, Not the Chaos

- Concrete Examples: Turning Common Birds Into Naive Icons

- Materials and Techniques That Keep It Playful

- Bird-Friendly Art Practices: Admire Without Interfering

- Conclusion: A Bird Can Be Accurate, and a Bird Can Be True

- My Experiences Making This Tribute (An Extra )

I have a soft spot for amateur bird paintingsthe ones where a cardinal looks like a red teardrop with ambitions, a heron is basically a folding chair with legs, and every owl has the startled expression of someone who just remembered they left the oven on.

These birds aren’t “wrong.” They’re honest. They’re painted the way birds feel when you notice them for the first time: loud color, strong shape, big personality, and a dash of mystery (plus, occasionally, a beak that appears to be attached with optimism alone).

This article is a love letter to that styleself-taught, folk, and proudly unbothered by the opinions of anyone who owns a ruler. We’ll dig into why amateur painters so often capture something surprisingly true about birds, how birdwatchers’ “field mark” thinking shows up in these paintings, and how I approached making tribute art that keeps the charm while still respecting what makes each species recognizable.

Why Amateur Bird Paintings Hit Us Right in the Feelings

Birds are familiar, but they’re never boring

Birds live close to uson wires, in hedges, on the most judgmental tree branch in the neighborhood. But they also behave like tiny mythological creatures who accidentally wandered into our parking lots.

That mix of everyday and magical is one reason birds have been a recurring subject in art for centuries, from careful natural studies to imaginative prints and drawings. Museums and archives keep showing how endlessly artists return to birds as symbols, design elements, and pure inspirationsometimes realistic, sometimes wildly interpretive, often both at once.

“Untrained” doesn’t mean “uninspired”

Major institutions actively collect and champion folk and self-taught art because it offers a powerful, personal visionart made outside formal academic pipelines, often with its own rules about space, detail, and storytelling.

In other words: these artists weren’t “missing” something. They were building something. And when birds enter that world, they come out as icons: simplified, bold, and emotionally legible from across the room.

The Secret Sauce: What Amateur Painters Do to Birds (On Purpose or Not)

They paint the bird’s “headline,” not the whole newspaper

A trained wildlife illustrator might carefully capture feather groups, lighting, and subtle proportions. An amateur painter often grabs the “headline” trait:

the red chest of a robin, the crest of a cardinal, the mask on a chickadee, the long legs of a heron. That’s not lazinessit’s great communication.

It’s the same logic birders use when identifying birds quickly: start with big signals, then refine.

They flatten spaceand the bird becomes a symbol

Amateur paintings frequently ignore perspective, shading rules, and realistic scale. The result can feel like a sign, a sticker, a storybook stamp: BIRD, presented confidently.

Flattened space also creates clarity. A bird on a branch becomes “bird + branch,” a clean visual sentence. And that “sentence” can be funny, sweet, dramatic, or weird in a way realism sometimes can’t.

They treat pattern like a party guest who won’t leave (and we love it)

Feathers are already pattern machines: bars, spots, scallops, streaks, iridescent flashes. Amateur painters lean into that, sometimes repeating patterns across the whole body like wallpaper.

This exaggeration isn’t scientifically precise, but it feels true to the experience of noticing a bird’s markings in motionquick, bold impressions that linger.

Borrow This From Birdwatchers: A Friendly “Field Mark” Mindset for Artists

Field marks: the bird’s ID badge

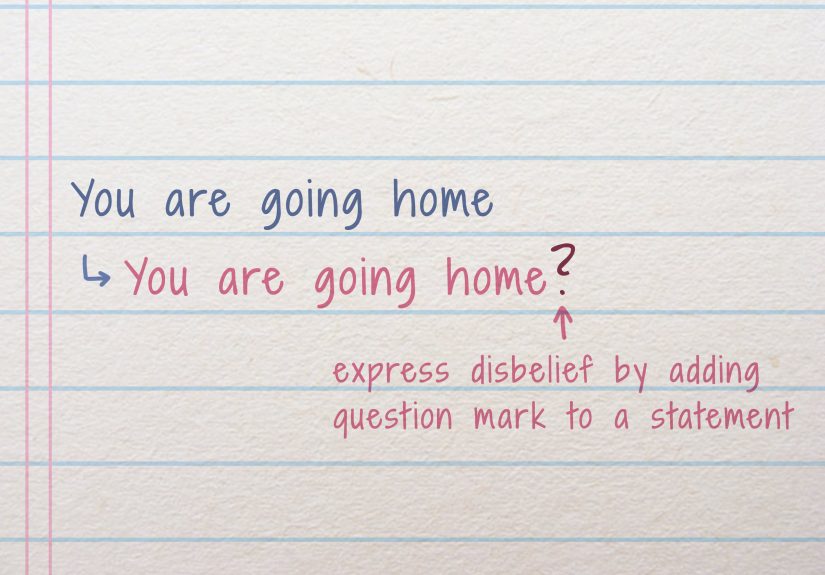

Birders talk about “field marks”distinctive stripes, patches, colors, and shapes that help separate one species from another.

For painters, field marks are a shortcut to recognizability. If your goal is a tribute to amateur style, you don’t need every feather. You need the marks that make someone say, “Oh! That’s a blue jay,” even if the jay looks like it pays taxes and owns a small boat.

Size and shape: the silhouette does most of the work

Before color, birders often register overall size and shape: chunky vs. sleek, long-tailed vs. short-tailed, big-headed vs. needle-nosed.

As an artist, silhouette is your best friend. If the silhouette reads, the painting workseven if you take creative liberties with the details.

Behavior and habitat: the vibe check that helps your composition

Birds don’t just look different; they act different. Some hug tree trunks. Some hop on lawns like they’re late for a meeting. Some glide like a slow, confident thought.

When you build behavior into your compositionposture, stance, head tilt, “what is this bird doing?”your amateur-style painting becomes more believable without becoming technical.

How I Built My Tribute Series: Keeping the Charm, Not the Chaos

Step 1: I chose birds people actually see

A tribute to amateur bird painters should feel like a memory: backyard birds, park birds, “I saw that guy near the grocery store” birds.

Starting with familiar species also makes simplification more meaningful. When everyone knows the general idea of a robin or cardinal, your stylization becomes a wink, not a puzzle.

Step 2: I designed each bird as a “character” first

Amateur paintings often treat birds like characters in a small drama: proud, suspicious, thrilled, mildly offended.

So I started with personality cues: chest-forward confidence for a cardinal, alert upright posture for a blue jay, calm loaf-shaped serenity for a dove.

Then I added species clues (crest, mask, wing bars) as supporting actors.

Step 3: I limited myself to a few bold shapes

My rule was simple: body, head, beak, tail, legsfive big shapes. Everything else was pattern or accent.

This constraint forced me to embrace the “amateur clarity” that makes these paintings so readable.

It also made each bird feel like it belonged to the same worldmy world of cheerful, slightly odd birds.

Step 4: I treated “mistakes” like style decisions

A beak too big? Now it’s a beak with confidence. A wing too short? Now it’s a wing that’s being modest.

The key is consistency: if you exaggerate, exaggerate on purpose and repeat the logic across the series.

Amateur paintings shine when they feel committed, not accidental.

Concrete Examples: Turning Common Birds Into Naive Icons

American Robin: the orange headline

What people remember: warm orange breast, upright stance, “I found a worm and I’m not sorry” energy.

In my tribute version, I kept the robin’s round belly and emphasized the orange chest as a bold shape rather than a gradient.

The eye became slightly too bigbecause amateur robins often look like they’re experiencing the miracle of Earthworms in real time.

I added a simple pale ring around the eye and a dark head shape, just enough to keep it grounded.

Northern Cardinal: crest + red, and you’re basically done

Cardinals are a gift to amateur painters because their field marks are so strong: bright red body, prominent crest, and a contrasting face area.

In tribute mode, I made the crest a clear triangle, almost like a tiny crown, and exaggerated the beak into a friendly wedge.

The bird reads instantly, even if the legs are suspiciously noodle-like.

That’s the charm: the cardinal becomes a symbol of “cardinalness.”

Blue Jay: wing bars as decorative jewelry

Blue jays have crisp patterning that amateur painters lovebars and patches that can be stylized into near-graphic design.

I treated the wing as a patterned banner: simplified stripes and blocks that repeat rhythmically.

The result feels both bird and ornament, like a living piece of folk textile.

Mourning Dove: the loaf with feelings

Doves can disappear into “generic gray bird” if you over-simplify. So I leaned into shape: an oval body, small head, gentle slope.

Then I added two key cues: a subtle dark spot on the cheek area and a long, tapered tail shape.

I also used soft transitionsstill amateur-friendly, but less “hard-edged,” because doves feel calm and quiet.

Great Blue Heron: elegant chaos on stilts

Herons are where amateur painters get hilarious (in the best way). Long legs. Long neck. Pointy beak. The geometry is already a cartoon.

In my tribute series, I made the legs nearly straight lines and turned the neck into a simple “S” curve.

Then I added the suggestion of a head stripe and a shaggy chest area using short brush marks.

It reads as heroneven if it also reads as “bird who could reach the top shelf without help.”

Materials and Techniques That Keep It Playful

Gouache and watercolor: bold, forgiving, and fast

Fast-drying paints encourage decisions. That’s perfect for an amateur tribute style, where hesitation can drain the joy.

Watercolor gives you lively blooms and surprises; gouache gives you opaque blocks and cheerful matte color.

Together, they let you build “graphic birds” that still feel hand-made.

Cheap brushes are sometimes the point

Perfect tools can tempt you into perfecting. Slightly imperfect tools push you toward gesture and shape.

A frayed brush makes feathery textures effortlessly. A stiff brush makes crisp, stamp-like marks.

The goal isn’t sloppiness; it’s freedom.

Collage: the “found feather” approach

Collage is a natural cousin to folk aesthetics. A strip of patterned paper becomes wing bars. A newspaper scrap becomes a branch.

Collage also lets you echo the way birds are built from repeating shapesfeather groups, layered surfaces, overlapping patterns.

Bird-Friendly Art Practices: Admire Without Interfering

Observe like a respectful neighbor

If you sketch outdoors, give birds space and avoid crowding nests or roosts. Let the bird set the terms.

If the bird changes behavior because you’re therestops feeding, alarm-calls, keeps looking at youback up.

Your art will be better when the subject is relaxed enough to be itself.

Use references ethically

Public-domain archives and museum collections can be a great starting point for learning shapes and poses.

But a tribute series isn’t about copying one photo perfectlyit’s about celebrating a style and a way of seeing.

Combine references, simplify, remix, and make something new.

Conclusion: A Bird Can Be Accurate, and a Bird Can Be True

Amateur bird paintings remind me that realism isn’t the only kind of accuracy. There’s also emotional accuracy:

the way a robin’s chest reads like a warm punctuation mark, the way a heron’s legs feel impossibly long, the way an owl’s stare can look like pure philosophical confusion.

My tribute art isn’t about laughing at amateur paintersit’s about learning from them. They show us how to prioritize what matters:

bold shape, recognizable field marks, confident pattern, and a bird that feels alive on the page.

If your painted bird ends up a little odd, congratulations. You’ve probably captured something real.

My Experiences Making This Tribute (An Extra )

The first thing I learned while making this tribute series is that “amateur” is not a style you can fake by simply being messy. I tried that early onsplattering paint, drawing crooked beaks, throwing color around like confettiand it looked forced, like a costume. The charm I was chasing didn’t come from randomness. It came from clarity. Amateur painters, especially the ones who paint birds from memory or quick observation, make strong choices. They decide what the bird is “about” and they commit.

So I started collecting tiny “bird truths.” Not scientific truthsfelt truths. A cardinal is a bright declaration. A sparrow is a small, busy thought. A pigeon is a confident sidewalk landlord. Once I wrote those down, my drawings got better immediately because my lines had a job. I wasn’t drawing a bird; I was drawing a personality with feathers.

The second surprise was how often my best paintings started as “mistakes.” One time I placed the eye too high on a chickadee and suddenly it looked adorably anxious, like it was hosting a tiny talk show about seeds. Instead of fixing it, I leaned in and made the whole series slightly wide-eyed. That became a signature. Another time I made a heron’s neck too short, and it stopped looking majestic and started looking like a lanky bird wearing a turtleneck. I laughed, then realized: that’s exactly the kind of honest weirdness I wanted. I repainted it three more times on purpose.

I also found myself borrowing from birdwatching without meaning to. When I was stuck, I stopped painting and asked the birder questions: What’s the silhouette? What’s the one field mark you’d bet a sandwich on? Where is the bird standing, and what is it doing? Those questions rescued me from overworking. Instead of fussing with feather detail, I’d paint the wing bar, the crest, the tail shape, and suddenly the bird “arrived.”

Finally, I learned that tribute art is a conversation. I wasn’t copying specific amateur paintings; I was responding to a tradition of joyful simplification. I began to imagine a friendly crowd of painters behind me, cheering whenever I chose a bolder color or simplified a shape. When I felt tempted to over-render, I pictured that crowd gently taking the tiny brush out of my hand and replacing it with a bigger one. “Paint the bird,” they seemed to say. “Not the anxiety.”

By the end of the series, my favorite part wasn’t finishing a perfect pieceit was recognizing that the “amateur” spirit is actually a professional-grade lesson in seeing. Birds move fast. They don’t pose. They don’t care about your portfolio. The best response is to paint with the same boldness birds live with: direct, lively, and completely uninterested in perfection.