Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why Your Hands Want One Set of Shortcuts

- Fusion Strategy #1: Teach Your Browser Some Emacs Manners

- Fusion Strategy #2: Edit Browser Text Areas in Real Emacs

- Fusion Strategy #3: Bring the Browser Into Emacs

- Bonus Fusion: Use a Browser That Already Speaks “Emacs-ish”

- How to Choose Your Fusion Level (Without Starting a Holy War)

- Practical Pitfalls (So You Don’t Rage-Quit at 2:00 AM)

- Conclusion: The Real Win Is Fewer Context Switches

- Field Notes: 10 Common “Aha” Experiences With Browser–Emacs Fusion (500+ Words)

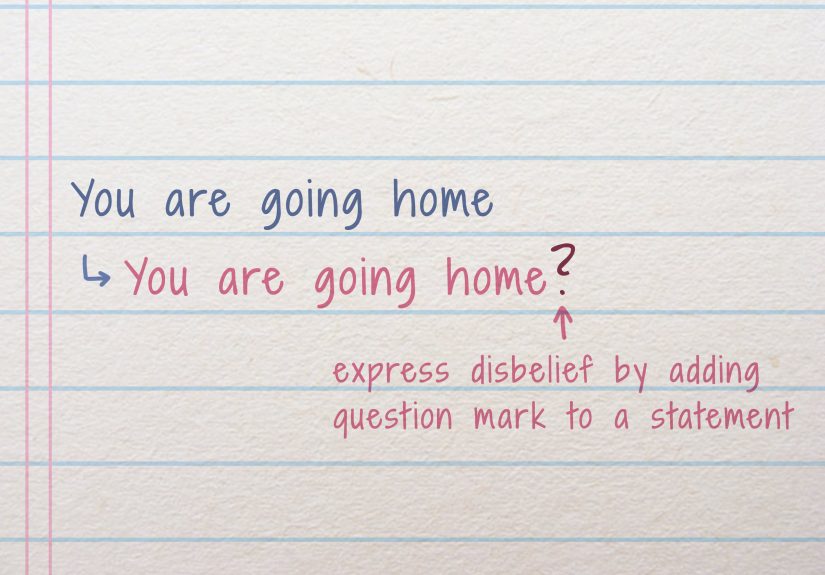

There are two kinds of people in the world: those who think Ctrl+S means “save,” and those who think it means

“start searching and don’t ask questions.” If you’re in the second camp (welcome), you’ve probably felt the tiny

daily papercut of context-switching: inside Emacs, your fingers are fluent; inside your browser, they suddenly start

speaking a different dialect.

The “Browser–Emacs Fusion” idea is simple: keep your muscle memory intact while you do modern work that lives in a

browserwriting docs, triaging tickets, editing Markdown, filling out forms, reviewing pull requests, even hacking on

web apps. The best part? You don’t need to turn your browser into Emacs (unless you want to). You can pick from a

menu of “fusion levels,” from lightweight keybinding tweaks to full-on “the browser is just another Emacs buffer.”

Why Your Hands Want One Set of Shortcuts

Emacs keybindings are less about nostalgia and more about repeatable motion. When your hands can

perform editing moves without your brain doing translation work, you write faster, edit more accurately, and stay in

flow longer. Browsers, however, are a mixed bag:

- Text fields behave like mini-editors, but not always consistently.

- Browser UI (tabs, address bar, devtools) has its own shortcuts that can conflict.

- Web apps often ship custom keymaps that override defaults.

- Modern Linux desktops might run Wayland, which changes how global hotkeys and automation work.

So the “fusion” problem isn’t one problemit’s three: (1) navigating and editing text inside the browser,

(2) writing long-form content in a real editor, and (3) optionally bringing web content into your editor-centric workflow.

Let’s solve them in the most practical order.

Fusion Strategy #1: Teach Your Browser Some Emacs Manners

Option A: Use a browser extension for Emacs-like navigation/editing

If you want the simplest on-ramp, start with browser extensions that add Emacs-style keybindings. These typically aim

to make common text-editing and navigation commands feel familiarthink cursor movement, killing/yanking text, and

basic “editor-ish” behaviors inside pages.

The trade-off is that browsers protect certain keystrokes for safety and consistency. Many extensions can’t fully

override internal pages, built-in UI, or shortcuts that the browser reserves. And some keybindings only work once a

page has fully loaded (which is exactly when you’re most likely to mash keys like a caffeinated woodpecker).

Still, for day-to-day browsing and editing in web forms, this approach can remove a huge amount of friction with

minimal setup and minimal risk.

Option B: Go system-wide with AutoKey (the “Linux Fu” approach)

Want something more “Linux Fu” than “click install”? Enter desktop automation tools like AutoKey.

The idea: AutoKey watches what you type and can trigger either text expansions (phrases) or

automation scripts (usually Python) that send keystrokes, paste text, or perform window-aware actions.

The key superpower here is scope. You can restrict automation to a specific application window

(for example, only your browser), so you don’t accidentally turn your spreadsheet into a chaos gremlin.

Once scoped, you can map Emacs muscle memory onto browser-native behaviors.

A practical example: in Emacs, Ctrl+S launches incremental search. In most browsers, Ctrl+F launches

find-in-page. A scoped AutoKey rule can translate Ctrl+S → Ctrl+F only in your browser.

You’re not recreating Emacsyou’re making the browser obey your hands.

Quick mapping ideas that tend to feel great:

- Ctrl+S → Find-in-page (browser search)

- Ctrl+K → “kill to end” inside text fields when web apps support it (or map to a browser-friendly equivalent)

- Ctrl+A / Ctrl+E → beginning/end of line (often already supported in many text inputs)

- Alt+F / Alt+B → forward/back word (supported in many inputs, but inconsistent across sites)

This approach shines when you want consistency across many sites, and you’re okay spending a bit of time tuning

shortcuts and dealing with edge cases. One important reality check for modern Linux users:

AutoKey is primarily an X11 tool. If your desktop session is Wayland, global key interception and

automation can be limited or nonfunctional.

If you’re on X11 and you live in your browser, AutoKey can feel like you installed “muscle memory compatibility mode.”

If you’re on Wayland, keep readingthere are fusion methods that don’t depend on global key interception.

Fusion Strategy #2: Edit Browser Text Areas in Real Emacs

Browser keybindings help, but they don’t turn a tiny text box into a real editing environment. The moment you’re writing:

a multi-paragraph comment, a Markdown README, a complicated Jira update, a long email, or anything with code blocks,

you want your real tools: your modes, your snippets, your spellcheck, your completion, your linter, your macros, your everything.

This is where “browser–Emacs fusion” becomes genuinely magical: instead of forcing the browser to behave like an editor,

you borrow Emacs to edit the browser.

GhostText + Emacs: the “open this textbox in Emacs” workflow

GhostText is a browser extension that can connect a web text field to a real editor via a local “server”

running in that editor. When you activate it on a textarea, the content opens in your editor and can stay synchronized.

In practice, this feels like you “popped out” the textbox into your real editing setup.

For Emacs users, one popular pairing is GhostText with atomic-chrome.el (often referred to simply as

Atomic Chrome for Emacs). It uses a local connection so changes can be reflected back and forth while you type, rather

than a clunky copy/paste loop. You get to keep Emacs features (like Markdown mode, Org tricks, or custom keymaps),

while the browser still receives the final text exactly where it needs to land.

Why it’s so effective for real work:

- Bidirectional updates make it feel “live,” not like exporting/importing text.

- Major modes matter: you can default to Markdown, org-ish workflows, or site-specific modes.

- Finish cleanly when you’re done, without leaving your editor in a weird state.

This method is also friendlier to Wayland environments because it doesn’t rely on global key interception. You’re

explicitly connecting an editor and a browser over a local channel. It’s a “consensual workflow,” not a “sneakily intercept keys”

workflow.

Atomic Chrome: Emacs-friendly editing with practical customization

Atomic Chrome for Emacs is worth calling out because it’s not just “open a buffer.” It’s a workflow you can tune:

choose whether updates are automatic, pick major modes based on URL/hostname patterns, and decide how buffers open

(split window vs. full window vs. new frame). That means you can build a setup that fits your specific web life:

GitHub comments in a GitHub-flavored Markdown mode, issue trackers in plain text, documentation sites in Markdown,

and so on.

The result is a fusion that feels less like a hack and more like a workstation feature: the browser becomes your

publishing surface, and Emacs becomes your writing engine.

Emacs Everywhere: the “edit anything with Emacs” philosophy

Another approach you’ll see in the Emacs ecosystem is the “Emacs Everywhere” style of workflow: trigger a command,

get an Emacs buffer to compose text, then send the result back into the app you were using. This style can be

especially useful beyond browserschat apps, issue tools, and any place that accepts text input.

Practically, it’s best when you want a quick “compose in Emacs” burst without maintaining a live synchronized connection.

Think of it like stepping into a writing booth, then returning to the stage with a finished paragraph.

Fusion Strategy #3: Bring the Browser Into Emacs

Now we’re entering the “dangerously cozy” zone, where Emacs stops being an editor and becomes an environment.

If you’ve ever thought, “I wish the web was just another buffer,” you’re not aloneand you have options.

Xwidget-WebKit: embedded browsing inside Emacs buffers

Emacs can be built with support for embedded WebKit widgets, which allows you to display web content in an Emacs buffer.

In that setup, you can browse to a URL and interact with a web view without leaving Emacs. There are also Emacs-specific

modes to help with search behavior inside the embedded content.

This can be great for quick reference: reading docs, checking an API page, opening a search result, or keeping a web UI

nearby while you code. It’s not always a perfect replacement for a full modern browser (websites can be heavy and complex),

but as a “keep the web in the same workspace” tool, it can be surprisingly handy.

Where it feels strongest:

- Documentation and reference pages

- Search results and quick lookups

- Keeping one web tool nearby while staying in an Emacs-driven workflow

EAF Browser: a more app-like browser experience within Emacs

If Xwidget-WebKit is “a web view in a buffer,” the Emacs Application Framework (EAF) aims to bring

fuller graphical applications into Emacs, including a browser. The EAF browser is designed as part of a larger system

that combines Emacs Lisp with external components (commonly Python and a GUI toolkit) to deliver richer experiences.

This approach appeals to people who want Emacs to be a hub for everything: browsing, PDFs, media, and morewhile keeping

Emacs key-driven habits in the driver’s seat. Like any deeper integration, it can involve more setup and more moving parts,

but the payoff is a unified environment.

Bonus Fusion: Use a Browser That Already Speaks “Emacs-ish”

Not all fusion has to happen by bolting parts onto a mainstream browser. Some browsers are built around keyboard-driven

navigation and deep programmability. One notable example is Nyxt, a Lisp-powered browser that emphasizes

customization and keyboard control. It even ships with modes that include Emacs-like keybindings in certain contexts.

The takeaway isn’t “switch browsers immediately.” It’s that the ecosystem has matured: if you want your browsing life to

feel closer to your editor life, you can do that in multiple waysextensions, automation, editor bridges, embedded browsing,

or an alternate browser philosophy.

How to Choose Your Fusion Level (Without Starting a Holy War)

Here’s a practical decision guideno gatekeeping, no purity tests, no “real Emacs user” nonsense:

-

If you mainly want familiar shortcuts:

start with a browser keybinding extension. Low effort, decent payoff. -

If you want consistent behavior across sites and apps:

consider AutoKey on X11 (or another desktop automation tool), scoped to your browser window. -

If you write long-form text in the browser:

GhostText + Atomic Chrome is often the biggest productivity jump. -

If you want the web inside Emacs:

explore Xwidget-WebKit or EAF Browser, and treat it like adding a new “app” to your Emacs world. -

If you want a keyboard-first browser lifestyle:

experiment with a highly programmable browser like Nyxt.

Practical Pitfalls (So You Don’t Rage-Quit at 2:00 AM)

Shortcut collisions are real

Some keys are sacred to browsers (tab management, address bar focus, devtools). If you remap aggressively, you might

“win” Emacs consistency but lose important browser behavior. The safest approach is to:

start with a small set of high-value remaps and expand only when you feel genuine friction.

Wayland vs. X11 changes what’s possible

On modern Linux desktops, Wayland can limit the kind of global key interception that older automation tools rely on.

If your workflow depends on system-wide key remapping, check your session type. If you’re on Wayland, lean toward

“explicit connections” (like GhostText/Atomic Chrome) instead of “intercept everything.”

Security and privacy: automation tools can see what you type

Any tool that watches keystrokes or injects text deserves a cautious mindset. Keep your scripts and expansions simple,

avoid logging sensitive input, and don’t blindly import random “productivity packs” from the internet. Your password manager

will thank you, and your future self will stop sending you angry emails.

Conclusion: The Real Win Is Fewer Context Switches

Browser–Emacs fusion isn’t about forcing one tool to replace another. It’s about protecting your flow. Sometimes that

means teaching your browser a handful of Emacs manners. Sometimes it means editing web text in Emacs through a live bridge.

And sometimes it means pulling the web into Emacs so your entire workday lives in one consistent mental model.

The best setup is the one that makes you forget the setup existsbecause your fingers stop hesitating and your attention

stays on the work, not the toolchain. Start small, choose the fusion level that matches your pain points, and iterate.

That’s the most Emacs thing you can do.

Field Notes: 10 Common “Aha” Experiences With Browser–Emacs Fusion (500+ Words)

The stories below aren’t “one perfect workflow” so much as a set of experiences people commonly report when they start

blending Emacs habits into browser work. If any of these sound familiar, you’re exactly the target audience for fusion.

-

The first time Ctrl+S stops betraying you.

When browser search starts responding to the same reflex you use in Emacs, you feel your shoulders drop.

It’s a tiny change, but it removes dozens of micro-pauses per dayespecially when you’re scanning long docs,

logs, or issue threads in the browser. -

Writing a “small comment” that turns into an essay.

You click into a web textbox planning to type two sentences. Fifteen minutes later you have headings, code blocks,

and regret. Opening that textbox in Emacs (via GhostText/Atomic Chrome) turns the moment from “oh no” into “cool,

I have my tools,” and you stop fearing comment boxes. -

Markdown suddenly feels like home again.

Many web editors are “mostly Markdown,” which is like saying a grocery cart is “mostly a car.” With an Emacs bridge,

you can use real Markdown major modes, previews, formatting helpers, and linting. The web app becomes the destination,

not the drafting environment. -

Site-specific modes become a productivity multiplier.

Once you map different sites to different major modes (GitHub-flavored Markdown here, plain text there),

your brain stops adapting to each website’s quirks. You also get better defaults: indentation, code fences, and

formatting conventions that match where you’re posting. -

You learn which keys are worth remappingand which ones are landmines.

The “aha” isn’t that you can remap everything; it’s that you shouldn’t. People often keep tab-management and browser UI

shortcuts intact, while focusing on text-editing and find/search behaviors. That balance preserves browser power

while restoring editor comfort. -

The Wayland moment.

Many folks discover that certain automation tools work great on X11 and mysteriously fail on Wayland.

The productive shift is recognizing two workflow categories: “global interception” versus “explicit connection.”

When you pivot to explicit editor-bridges, you get reliability without fighting the compositor. -

Emacs becomes your “single source of writing truth.”

Once you draft in Emacseven for web-only contentyou can reuse snippets, keep templates, run consistent spellcheck,

and store reusable text in files under version control. The browser becomes a publishing interface, not a drafting tool. -

Search inside embedded web views feels oddly satisfying.

If you try embedded browsing inside Emacs (xwidget-based), the novelty fades fastbut the convenience sticks.

Checking docs in an Emacs buffer next to code, then jumping back without window gymnastics, can feel like cheating

(the good kind). -

Your “workflow” becomes a set of small, reliable moves.

People often stop chasing the mythical perfect setup and instead build a handful of dependable actions:

“open textbox in Emacs,” “finish with a key,” “use the right mode,” “close cleanly.” These small moves compound into

a calmer day. -

You realize the point isn’t Emacsit’s fewer context switches.

The biggest win isn’t ideological. It’s practical: fewer mental gear shifts, fewer broken thoughts, and more time

spent actually writing, reviewing, and building. The browser–Emacs fusion is just a tool for protecting focus.