Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

Trying to rank Milan Kundera’s novels is a little like ranking your existential crises:

the more you think about it, the more complicated it gets. Still, readers, critics, and

book clubs keep doing it. From university syllabi to online polls and Goodreads lists,

a loose consensus has emerged around which Kundera books are essential, which are

“for fans only,” and which ones you save for the kind of rainy weekend when you’re

emotionally prepared to ponder history, sex, memory, and the futility of human plans.

In this guide to Milan Kundera rankings and opinions, we’ll walk through

his most talked-about works, how readers in the English-speaking world tend to rate them,

and what themes make them so unforgettable. Think of it as a friendly, slightly nerdy

reading map rather than a final verdict handed down from the literary Supreme Court.

Why Rank Milan Kundera At All?

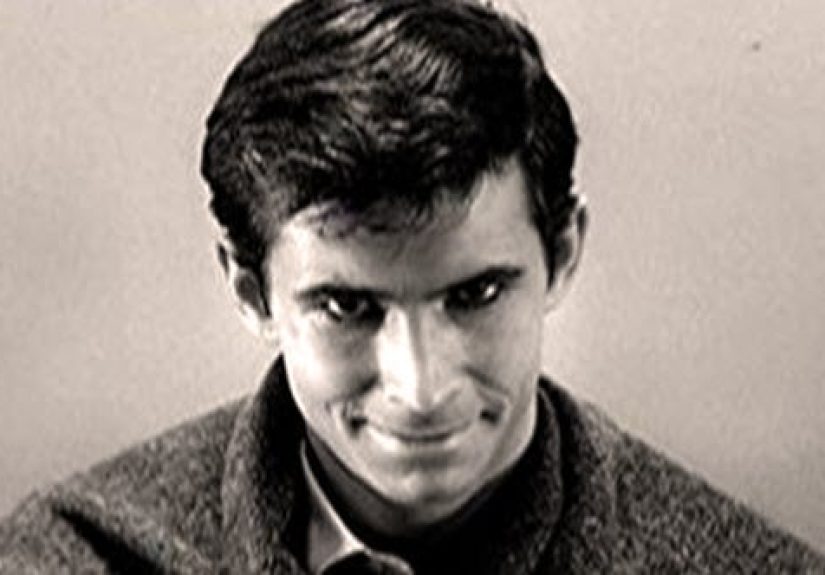

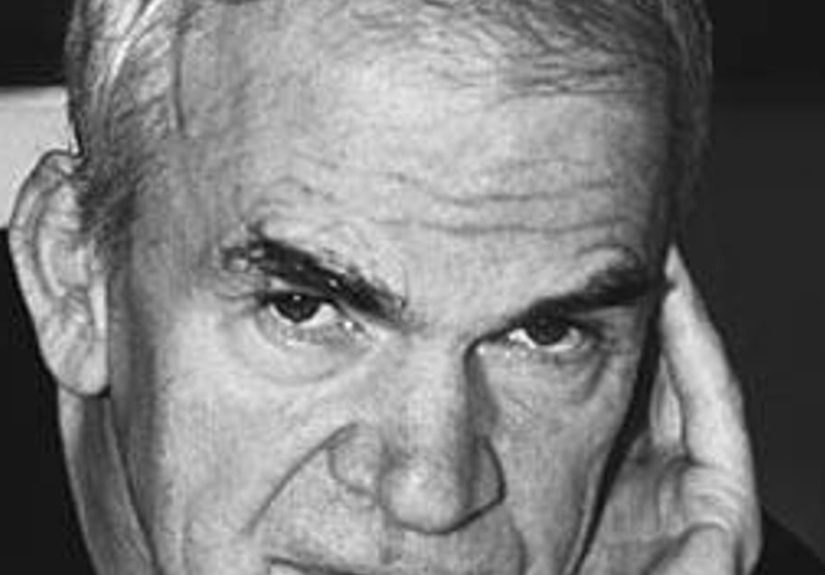

Milan Kundera (1929–2023) was a Czech-French novelist who spent much of his life in exile,

first under Communist censorship and later as a fiercely private writer in France. His

novels mix philosophy and farce; you’ll find jokes about party meetings in the same breath

as meditations on Nietzsche, memory, and the weight (or lightness) of human choices.

Because he wrote across decades, in both Czech and French, and with wildly different tones

from the political bite of The Joke to the airy melancholy of

The Festival of Insignificance new readers often ask: where do I start, and

what’s considered his “best” work? That’s where rankings and crowd opinions become helpful.

They give a rough map of what the global reading community loves most,

even if your personal top three might end up completely different.

Top Milan Kundera Novels, Ranked

The list below blends critical reception, reader ratings on major book platforms, frequent

recommendations from critics and book sites, and years of fan discussion online. It’s not

scientific, but it reflects how Kundera is generally perceived in the English-language

literary world.

1. The Unbearable Lightness of Being

If Kundera has a “greatest hit,” this is it. The Unbearable Lightness of Being

consistently tops lists of his best novels and appears on countless “modern classics”

lists. Set in Czechoslovakia around the Prague Spring, it follows Tomas, Tereza, Sabina,

and Franz through tangled love affairs, political repression, and big questions about what

it means to live a meaningful life when everything feels fleeting.

Readers rank it highly for its unforgettable scenes (yes, the bowler hat), its blend of

eroticism and political reflection, and the way it drops philosophical riffs right in the

middle of everyday drama. Some readers find the detached, authorial commentary jarring;

others think that voice is the entire point. If you like character-driven novels spiced

with philosophy and a touch of chaos, this is the top of most

Milan Kundera rankings.

2. The Book of Laughter and Forgetting

Often ranked just behind Unbearable Lightness,

The Book of Laughter and Forgetting is a fragmented book in seven parts that

circles around memory, forgetting, exile, and the ways totalitarian regimes rewrite

history. It’s formally playful you get stories, essays, and surreal episodes that echo

one another instead of a single, linear plot.

Critics love how this book shows Kundera at his most inventive: there are flying

schoolgirls, disappearing photographs, and lovers caught between private desire and public

lies. Readers who enjoy nonlinear storytelling and big metaphors tend to rank it very

highly. If you like novels that feel like puzzles made of memory and politics, this is

usually in the top three of any Kundera opinion list.

3. The Joke

The Joke was Kundera’s breakout novel and remains one of his most

politically charged works. The “joke” in question is a sardonic postcard a student

sends to his girlfriend, which gets him expelled from the party and derails his life.

What follows is a story about revenge, humiliation, and the absurd seriousness of

totalitarian bureaucracy.

Many readers and critics put The Joke in their top three because it combines a

sharp critique of Communist Czechoslovakia with very human portraits of pettiness and

desire. Compared with some later works, its plot is more traditional, which makes it a

good entry point if you’re wary of experimental structure but still want all the

philosophical juice.

4. Immortality

For some fans, Immortality is the Kundera masterpiece. The novel opens

with the author noticing the elegant wave of an older woman in a Paris swimming pool and

spins that moment into a labyrinth of stories about identity, fame, and how we are

remembered (or misremembered) after we die.

It weaves together fictional characters with historical figures like Goethe and Hemingway,

blurring lines between author and character. Readers who like metafiction and novels that

talk back to themselves often rank Immortality above even

Unbearable Lightness. Others find it a bit too airy and self-referential. In

most consensus rankings, it lands solidly in the top five.

5. Laughable Loves

Technically a short story collection, Laughable Loves still shows up in many

Milan Kundera opinions lists as one of his most enjoyable works. Each

story explores the games people play in love, sex, and self-presentation, often with dark

humor and a twist that exposes the character’s illusions.

Because the stories are compact and playful, lots of readers recommend

Laughable Loves as a way to “test drive” Kundera’s voice before diving into a

big novel. It doesn’t always rank at #1, but it’s frequently cited as a favorite and a

great place to see his comic side without a heavy political backdrop.

6. Life Is Elsewhere

Life Is Elsewhere targets the figure of the romantic revolutionary poet the

kind of earnest young man who believes his feelings and slogans can change the world.

Kundera’s take is compassionate but ruthless, showing how narcissism and ideology can

mix into something both ridiculous and dangerous.

Opinions on this one are more split. Some readers love its satire of youthful idealism and

its portrait of a mother-son relationship that’s as suffocating as any political regime.

Others find it more demanding than his later work. In rankings, it usually falls in the

middle: respected, sometimes adored, rarely anyone’s absolute favorite.

7. Ignorance

A sleeker, later novel, Ignorance follows two Czech émigrés returning home after

years abroad, grappling with what has changed and what has been frozen in memory. The

book uses the myth of Odysseus to ask: is going home really what we want, or do we just

want the idea of the home we left?

Many readers who have moved countries themselves rank Ignorance surprisingly

high because its reflections on exile and nostalgia hit close to home. In general lists,

it’s often placed just below the major classics, as a compact, underrated gem in the

Kundera canon.

8. Slowness

Slowness is the first novel Kundera wrote in French, and it feels like a

manifesto against modern speed. It juxtaposes 18th-century seduction games with a modern

academic conference to explore memory, pleasure, and the art of lingering.

Opinions here are polarized. Some readers rank it high for its elegance and the way it

meditates on what digital-age life was about to become. Others find it slight compared

with his big Czech novels. In most rankings, it ends up in the “for fans” tier not

where you start, but rewarding once you’re already hooked.

9. Identity

Identity is a short, slippery book about a couple whose sense of self and

relationship begins to fracture over a series of misunderstandings and mysterious letters.

Reality and fantasy blur as Kundera asks what, exactly, we fall in love with the other

person, or a story we’ve built around them.

In reader rankings, Identity seldom breaks into the top tier, but it has its

defenders, especially among those who like compact, psychological fiction. It’s often

described as “late-career experimental Kundera,” with all the strengths and oddities that

phrase implies.

10. The Festival of Insignificance

Kundera’s last novel in French, The Festival of Insignificance, is short, airy,

and intentionally insubstantial. It follows a group of friends in Paris through

conversations that drift from jokes about Stalin to reflections on mortality and the

meaning (or meaninglessness) of everyday life.

Critics and readers are sharply divided. Some see it as a wise, playful farewell; others

thought it felt like an echo of earlier themes without the same power. Most rankings put

it near the bottom of the list not because it’s bad, but because the earlier novels set

such a high bar.

Other Ways Readers Rank Kundera

Formal tier lists are only one angle. When you dig into reader forums, reviews, and

essays, you’ll see other “ranking systems” emerge that are just as revealing.

By Accessibility

-

Most accessible:

The Unbearable Lightness of Being,

Laughable Loves, Ignorance.

Clear plots, emotional hooks, and just enough philosophy to be intriguing without

requiring a seminar. -

Moderately demanding:

The Joke, Immortality,

The Book of Laughter and Forgetting.

Deep political context and more experimental structure, but still very readable. -

Most challenging:

Life Is Elsewhere, Slowness,

Identity, The Festival of Insignificance.

Best tackled once you’re used to his digressive style and recurring obsessions.

By Emotional Impact

Ask fans which book “wrecked” them and you’ll often hear the same titles over and over:

-

The Unbearable Lightness of Being for its devastating treatment of love,

betrayal, and the randomness of political violence. -

The Book of Laughter and Forgetting for its haunting images of erased people

and disappearing histories. -

Immortality for the way it quietly dismantles our fantasies about how we’ll be

remembered.

Even readers who are skeptical of Kundera’s philosophy often admit that these books lodge

themselves in your mind long after you’ve closed them.

Key Themes That Shape Rankings And Opinions

Part of what makes Kundera so rank-able and so endlessly debatable is how consistently

he returns to certain themes, even as his style changes. When readers talk about why they

love or dislike specific books, they’re often reacting to how these themes show up.

Exile and Homecoming

From The Joke and Ignorance to essays in

The Art of the Novel, Kundera circles the experience of being exiled from one’s

country, language, or past. Readers who have emigrated, or who come from politically

turbulent places, tend to rank these books higher. The tension between staying and

leaving, remembering and forgetting, is one of the strongest emotional cores in his work.

Memory, Forgetting, And History

The title The Book of Laughter and Forgetting could describe half his oeuvre.

Kundera is fascinated by how individuals and nations curate memory: which events are

celebrated, which are erased, and how private recollections clash with official history.

Some readers adore this; others feel the essayistic detours pull them away from the

characters. Where you land on that question often affects how you rank each book.

Eroticism and the Comedy of Desire

Kundera writes about sex with a mix of seriousness and mischief. Relationships in his

novels are rarely tidy: they’re full of games, self-deception, and mismatched expectations.

Fans argue that this makes the books feel brutally honest; critics sometimes find his

portrayals of women and desire dated or unbalanced.

This tension shows up clearly in opinions of

The Unbearable Lightness of Being.

For some, it’s one of the most honest portraits of love under pressure; for others, it’s

maddening in its treatment of female characters. The same text, radically different

rankings all part of the Kundera experience.

Irony, Play, And the Authorial Voice

Unlike many novelists, Kundera steps into his books as a commentator. He’ll pause the

action to explain a symbol, riff on philosophy, or argue with other writers. If you love

that playful, intrusive voice, books like Immortality and

The Book of Laughter and Forgetting shoot up your list. If you prefer invisible

authors, you may rank his more straightforward early novels higher.

Where Should You Start With Milan Kundera?

Based on how readers and critics talk about him, here’s a simple, mood-based approach:

-

“I want his most famous book and I’m okay with some philosophy.”

Start with The Unbearable Lightness of Being. This is the one everyone references. -

“I love short stories and dark humor.”

Go for Laughable Loves. It’s like a tasting menu of Kundera’s obsessions. -

“I want something political but still novelistic.”

Try The Joke, which hits the sweet spot between narrative drive and political

critique. -

“I enjoy experimental, essay-like fiction.”

Choose The Book of Laughter and Forgetting or Immortality.

These are the books that fans of postmodern fiction tend to rank highest. -

“I’m an émigré or just obsessed with the idea of ‘home’.”

Ignorance will probably go straight into your personal top three.

The real secret? No ranking is permanent. Many readers report that their favorite Kundera

novel changes depending on their age, political mood, and how nostalgic they feel when

they pull a battered paperback off the shelf.

Of Experiences And Reflections On Kundera Rankings

Spend enough time lurking in book forums or talking to people who discovered Kundera in

college, and you’ll notice a pattern: everyone has a story about the first time they met

his work, and that first encounter often shapes their rankings for years.

Some readers meet Kundera in a philosophy or literature class, where

The Unbearable Lightness of Being is assigned alongside discussions of Nietzsche

and political theory. For them, the book becomes part of a broader intellectual awakening.

They remember staying up late underlining passages about eternal return and “lightness”

versus “weight,” convinced the novel was secretly explaining their love life and their

midterm anxiety at the same time. It naturally becomes their #1 not just as a novel,

but as a milestone.

Others come in through Laughable Loves, often by accident. Maybe a friend hands

them a copy with a mischievous, “You’ll either love this or curse me.” The stories feel

sharp and modern: people sabotaging their own relationships, flirting with cruelty,

discovering that the joke has turned on them. For those readers, Kundera is less the

solemn philosopher of Eastern Europe and more the guy who understands that romance is

usually a tragicomedy. Their rankings often start with:

“Laughable Loves is the real masterpiece; the big novels are just bonus content.”

Then there are the readers who pick up Immortality or

The Book of Laughter and Forgetting not because of a syllabus, but because

someone told them, “This feels like a conversation rather than a story.” They’re the ones

who don’t mind when the narrative stops so the author can muse about Goethe or history or

the meaning of a gesture. To them, those digressions are the good part. In their personal

rankings, the more essayistic a novel is, the higher it climbs.

A lot of divided opinions come from readers’ expectations about love stories. Someone who

walks into The Unbearable Lightness of Being expecting a straightforward romance

might be shocked by how cold or inconsistent the characters seem. They may rank the book

lower, calling it “emotionally distant.” Another reader, seeing the same scenes, thinks:

“Finally, a novel honest enough to admit that people are contradictory and selfish, even

when they’re in love,” and the book lands at #1 forever.

Age and experience also reshape Kundera rankings over time. A reader in their twenties

might identify with the restless idealism of Life Is Elsewhere or the erotic

drama of Unbearable Lightness. Revisit the same books in your forties or fifties,

and suddenly the exiles in Ignorance or the aging characters in

Immortality hit much harder. The ranking quietly rearranges itself: books you

once thought minor become central, and early favorites take on a more complicated glow.

Finally, there’s the experience of confronting the late works, especially

The Festival of Insignificance. Many readers approach it with a strange mix of

reverence and skepticism: is this a profound final statement or just a light coda to a

heavy career? Reading it after the big Czech novels feels a bit like watching a legendary

musician play quiet encores after a thunderous main set. Some walk away disappointed,

nudging it to the bottom of their list. Others find the very lightness the refusal to

deliver one last heavy thesis oddly moving. For them, that book becomes a kind of secret

favorite, not because it’s the “best,” but because it asks you to stop ranking and just

listen.

In the end, Milan Kundera rankings and opinions tell you as much about

the readers as they do about the books. Your own list will be shaped by which title you

picked up first, where you were in your life, and whether you read him for the politics,

the philosophy, the jokes, or the heartbreak. The fun part is that you’re allowed to

change your mind and, in true Kundera fashion, laugh at your past self while you do it.