Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Scientists Actually Mean When They Say “Masks Work”

- How Masks Block Germs: The Simple Physics

- Not All Masks Are Created Equal

- What the Evidence Says: Lab Studies and Real-World Data

- Why Headlines About Masks Can Sound Confusing

- When Masks Make the Most Sense Today

- How to Wear a Mask So It Actually Works

- Who Benefits Most from Masking?

- Common Myths About Masks (And Why They Don’t Hold Up)

- Science-Based Medicine and Making Informed Choices

- Real-World Experiences: What Masking Looks Like Day to Day

- Bringing It All Together

Remember when masks were the main character of every grocery store trip, school drop-off,

and family group chat? Even though the headlines have moved on, respiratory viruses

definitely haven’t. And every time there’s a new wave, the same question pops up:

do masks really work?

Short answer: yes, masks work not as magical force fields, but as one very useful layer

in a bigger protection strategy. The longer answer is more interesting (and more nuanced),

and that’s what we’re going to unpack here, pulling from science-based sources,

expert guidance, and real-world experience.

What Scientists Actually Mean When They Say “Masks Work”

In everyday conversation, “works” can sound like “guarantees I’ll never get sick.”

That’s not how public health or science uses the word. When researchers say

masks work, they mean:

- Masks reduce the risk that infected people will spread virus-laden particles to others.

- Masks reduce the dose of virus that you breathe in, which may lower your chance of infection or severe illness.

- Across a whole community, widespread masking can mean fewer infections overall, fewer hospitalizations, and fewer deaths.

Think of masks like seat belts. Wearing a seat belt doesn’t guarantee you’ll walk

away from a car crash without a scratch, but it absolutely improves the odds.

Masks do something similar for respiratory viruses like COVID-19, flu, and RSV.

How Masks Block Germs: The Simple Physics

Every time we talk, cough, sneeze, sing karaoke off-key, or shout at a referee on TV,

we launch a small cloud of droplets and aerosols into the air. Some of those particles

can carry viruses if we’re infectedeven before we feel sick.

Masks work by:

- Trapping larger droplets that would otherwise spray out into the air.

- Filtering smaller particles as air passes through layers of material.

- Redirecting airflow so fewer particles shoot straight at the person next to you.

High-quality respirators (like N95s) are designed to filter out at least 95% of very

small particles when they fit properly. Surgical masks are less tight but still block

a lot of droplets and some aerosols. Even a decent, multi-layer cloth mask is better

than nothing when other options aren’t available.

Not All Masks Are Created Equal

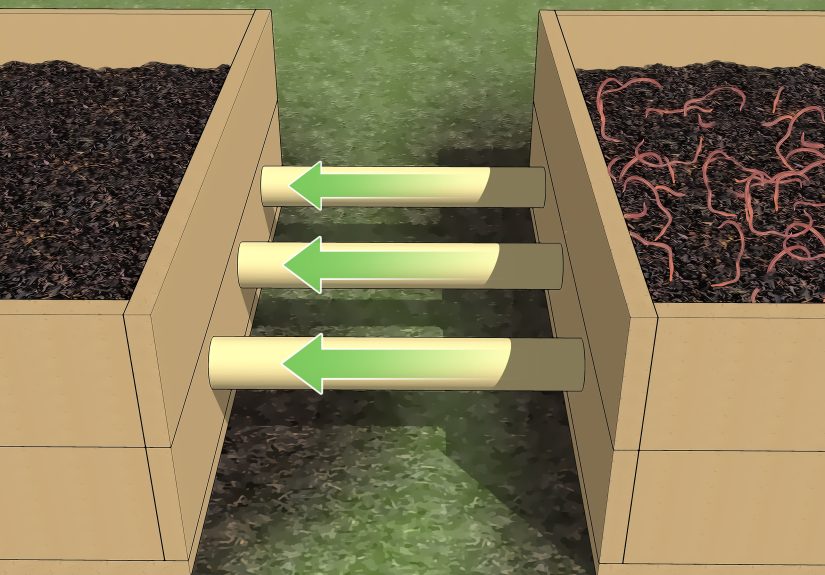

One of the big lessons of the past few years is that mask type and fit matter.

Here’s a quick, practical breakdown:

Respirators (N95, KN95, KF94)

- Designed to filter a very high percentage of small particles when properly fitted.

- Best choice for crowded indoor spaces, healthcare settings, or when transmission is high.

- Work best when the edges seal snugly around your face no big gaps at the cheeks or nose.

Surgical / Medical Masks

- Loose-fitting but made from material that filters droplets and some aerosols.

- Better than cloth masks alone and widely available.

- Can be upgraded by knotting the ear loops and tucking in the sides, or by using a mask brace to improve fit.

Cloth Masks

- Protection depends heavily on fabric quality, layers, and fit.

- Multiple layers of tightly woven fabric are much better than a thin, single-layer fashion mask.

- Best used when higher-grade masks aren’t available, or layered over a surgical mask to improve fit.

Whatever type you choose, a badly worn mask (below the nose, dangling from one ear,

acting as a chin hammock) is basically just a facial accessory, not a health tool.

What the Evidence Says: Lab Studies and Real-World Data

Let’s talk science, not vibes. Researchers have looked at masks from multiple angles:

in laboratories, in hospitals, in households, in schools, and across entire communities.

Lab and Mechanistic Studies

In controlled settings, masks do exactly what they’re supposed to do:

- They block droplets of the size known to carry respiratory viruses.

- They reduce the amount of viral material measured in the air when people wear them.

- High-filtration respirators outperform surgical and cloth masks, especially against aerosols.

These studies are like crash tests for masks: they tell us the potential performance

when masks are used correctly and consistently.

Real-World Studies and Systematic Reviews

Real life is messier: people fidget with masks, wear them incorrectly, take them off to talk,

or skip them entirely. Even so, reviews of dozens of observational studies have generally found:

- Mask wearers often have a lower risk of infection compared to non-wearers.

- Higher-quality masks (N95-style respirators) tend to offer greater protection than basic cloth masks.

- Communities with mask policies often show reduced transmission compared with similar places without such policies, especially when compliance is high.

Some studies show stronger effects than others, and a few show little or no difference.

That’s normal in public health research, especially when human behavior is a big part

of the equation. But when you zoom out and look at the totality of evidence, the pattern

is clear: masks are a useful tool to reduce transmission, particularly as part of

a broader strategy that includes ventilation, vaccination, testing, and staying home when sick.

Why Headlines About Masks Can Sound Confusing

If you feel like you’ve seen news stories that say “masks work” one week and

“masks don’t work” the next, you’re not alone. Here’s what’s usually going on:

- Different questions, different answers. A study asking “Do masks completely prevent infection?” will get a different answer than one asking “Do masks reduce risk at the population level?”

- Different settings. A well-supplied hospital with fit-tested respirators isn’t the same as a school where half the class wears thin cloth masks under their noses.

- Adherence problems. If people are assigned to “mask groups” but don’t actually wear them consistently, the benefit will look smallereven if masks themselves are effective.

- Political noise. Mask debates got tangled up with politics, personal identity, and misinformation, which made it harder for nuanced scientific messages to get through.

A science-based approach doesn’t cherry-pick one convenient study. It weighs the entire

body of evidence, including limitations, and asks the more practical question:

“Does this intervention help more than it hurts?”

For masking in high-risk situations, the answer is still yes.

When Masks Make the Most Sense Today

Public health guidance has shifted from “mask everywhere, all the time” to something more

targeted and risk-based. In most current recommendations, masks are especially encouraged:

- When you have symptoms of a respiratory virus or have recently tested positive.

- For a period after you’re feeling better, to lower the chance of still spreading infection.

- In crowded indoor spaces, especially with poor ventilation.

- On public transportation during high transmission periods.

- If you live with or visit people who are older, immunocompromised, pregnant, or have chronic conditions.

- In healthcare settings, where vulnerable patients are concentrated.

Instead of treating masks as a permanent lifestyle, think of them more like an umbrella:

you don’t carry it every day because of a single raindrop in the forecast, but when the sky

turns dark, you’re glad to have it.

How to Wear a Mask So It Actually Works

If you’re going to bother wearing a mask, you might as well get full value out of it.

A few simple habits turn “mask as decoration” into “mask as protective gear”:

- Cover both nose and mouth. If your nose is out, you’re basically using the mask as a lower-lip warmer.

- Check the fit. Air should go through the mask, not around it. Adjust the nosepiece and ear loops to reduce gaps.

- Choose the best mask you can comfortably wear. A perfectly sealed respirator you rip off after five minutes is less useful than a good mask you’ll keep on.

- Handle it by the ear loops or straps. Avoid constantly touching the front of the mask, especially with unwashed hands.

- Replace masks that are wet, dirty, or damaged. A damp mask is less effective and much less pleasant.

These sound like small details, but they add upespecially in places where many people

are masked at the same time.

Who Benefits Most from Masking?

While anyone can benefit from cutting down their exposure to respiratory viruses,

masking can be especially impactful for:

- Immunocompromised people or those on treatments that weaken the immune system.

- Older adults and people with heart, lung, or kidney disease.

- Pregnant people, who face higher risks from certain infections.

- Caregivers who can’t easily avoid close contact with vulnerable loved ones.

- Healthcare workers and others in high-exposure jobs.

For these groups, a well-fitting high-filtration mask can be the difference between

“mild inconvenience” and “serious health event.” But even if you’re young and healthy,

masking can help protect the people around youespecially when you might be contagious

before you feel sick.

Common Myths About Masks (And Why They Don’t Hold Up)

“Masks Don’t Work Because Some People Got Sick Anyway”

No preventive measure is perfect. People still get into accidents even with seat belts,

but we don’t throw out seat belt laws. The question isn’t “Did anyone ever get sick

while wearing a mask?” but rather “Do people who mask correctly get sick less often

than those who don’t?”

“Masks Cause Dangerous Carbon Dioxide Buildup”

For the general public, there’s no credible evidence that properly worn masks cause harmful

CO2 buildup. Healthcare workers have worn surgical masks and respirators for long

shifts for decades. Are they thrilled about it? Not always. But serious harm from CO2

buildup in healthy people just isn’t a thing.

“If Masks Worked, We Would Have Eliminated COVID-19”

Masks are one tool, not a magic off-switch. Viruses spread through multiple

paths and thrive on inconsistent human behavior. Masking, ventilation, vaccination, testing,

and staying home while sick all work better together than any one measure alone.

Science-Based Medicine and Making Informed Choices

A science-based approach to medicine and public health doesn’t mean never changing your mind.

It means updating your views as better evidence comes in, accepting nuance,

and resisting the urge to oversimplify complex questions into “always” or “never.”

With masks, the story isn’t:

“They were useless and we should never have bothered.”

The story is:

- Masks are physically capable of blocking respiratory droplets and filtering aerosols.

- When worn correctly and consistently, they reduce individual and community risk.

- They are most useful in high-risk settings and when paired with other protections.

- They carry relatively low cost and risk compared with the potential benefit, especially for vulnerable populations.

That’s what “one more time – masks work” really means: not that masks are perfect,

but that they are worth using thoughtfully when the situation calls for it.

Real-World Experiences: What Masking Looks Like Day to Day

Data and graphs are great, but most of us make decisions based on lived experience as much

as numbers. Over the last few years, people have quietly built their own “masking playbooks”

based on what’s worked in real life.

The Teacher Who Wants to Keep Class in Class

Picture a middle school teacher who spent the early pandemic bouncing between in-person,

remote, and hybrid teaching. She noticed that during the years when her school encouraged

masking and improved ventilation, her class didn’t just have fewer COVID-19 cases

there were fewer “mystery viruses” in general. Absences dropped. Group projects actually

stayed on schedule. Her personal takeaway wasn’t “mask forever,” but rather:

“When there’s a nasty wave going around, it’s worth putting on a good mask for a few weeks

if it means keeping my students in class and myself out of bed.”

The Healthcare Worker Who Can’t Work from Home

For nurses, respiratory therapists, and other frontline healthcare workers, masks and

respirators have always been part of the job. COVID-19 turned that dial up to eleven,

but the principle stayed the same: when you’re surrounded by people with contagious illness,

barriers matter. Many healthcare professionals now keep a small stash of N95s in their car

or bag, not just for work but for situations like crowded airports or visiting a vulnerable

family member after a long shift.

The Immunocompromised Friend at the Dinner Table

Maybe you’ve got a friend or relative who’s undergoing chemotherapy, living with an organ

transplant, or managing an autoimmune condition. For them, “just a cold” can turn into a

hospital visit. Some families have settled into simple, compassionate routines:

people test before visits when possible, crack open a window, use a portable air purifier,

and wear masks until everyone’s seated and the food arrives. Is it perfect? No.

Is it dramatically better than pretending viruses don’t exist? Absolutely.

Everyday Masking: Airports, Trains, and Winter Waves

You can see the new “normal” strategy in airports and train stations. Even when mandates

are long gone, there’s always a noticeable subset of travelers in high-filtration masks.

These aren’t necessarily the most anxious people often they’re the ones who simply

don’t want to spend their vacation hacking in a hotel bed. They’ve done the math:

a few hours in a mask during the flight is a small trade-off if it lowers their odds

of dragging home an unwanted viral souvenir.

Similarly, when winter rolls around and everyone at the office seems to be coughing,

plenty of people now treat masks as a practical tool rather than a political statement.

They pop one on for the bus ride, the crowded elevator, or the trip to the pharmacy.

Not 24/7, not foreverjust when the risk feels obviously higher.

Learning from the “Quiet Wins”

One of the more striking, if underappreciated, experiences of the pandemic era was how

dramatically some communities saw drops in flu and other respiratory illnesses during periods

of strong masking and distancing. As those measures relaxed, those viruses came roaring back.

That bounce-back isn’t proof that masks never mattered; it’s a sign that they really did.

The lesson many people have taken forward is simple:

you don’t need to mask all the time for masks to be useful.

You just need to use them strategically during surges, in crowded indoor spaces,

around vulnerable people, and when you’re sick but absolutely must be around others.

Bringing It All Together

So where does that leave us? Masks are not a symbol, a political litmus test, or

a forever lifestyle requirement. They are a tool a simple, relatively low-cost,

low-risk way to tilt the odds in favor of fewer infections and less severe illness,

especially when viruses are surging.

Used with common sense and grounded in science-based medicine, masks don’t promise perfection.

They offer something more realistic and more useful: better odds for you,

your family, and your community when respiratory viruses are in the air.

Not magic. Not meaningless. Just one more time, for the people in the back:

masks work especially when you use them well, when they matter most.