Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What is polycythemia vera (PV), and why does it affect life expectancy?

- Polycythemia vera life expectancy: What the numbers actually mean

- The single most important treatment target: Keep hematocrit under control

- PV treatment options that can improve prognosis

- What influences life expectancy in PV?

- Does treatment “cure” PV or just manage it?

- Monitoring: The “maintenance plan” that supports longevity

- Daily-life choices that can protect your prognosis

- Long-term risks: progression to myelofibrosis or leukemia

- Frequently asked questions about PV life expectancy

- Conclusion: PV prognosis is often about prevention, not prediction

- Experiences: What living with PV can feel like (and how people adapt)

- SEO Tags

Getting diagnosed with polycythemia vera (PV) can feel like someone handed you a mystery novel where the villain is your own bone marrow.

The good news: PV is usually slow-moving, highly treatable, and for many people it becomes a “manage-it-like-a-chronic-condition” situation rather than

an immediate emergency.

The tricky part is that PV’s biggest danger isn’t dramatic symptomsit’s the quiet, sneaky stuff: blood clots, stroke, heart attack, and (in a smaller

number of cases over time) progression to myelofibrosis or acute leukemia. That’s why treatment is so focused on prevention.

What is polycythemia vera (PV), and why does it affect life expectancy?

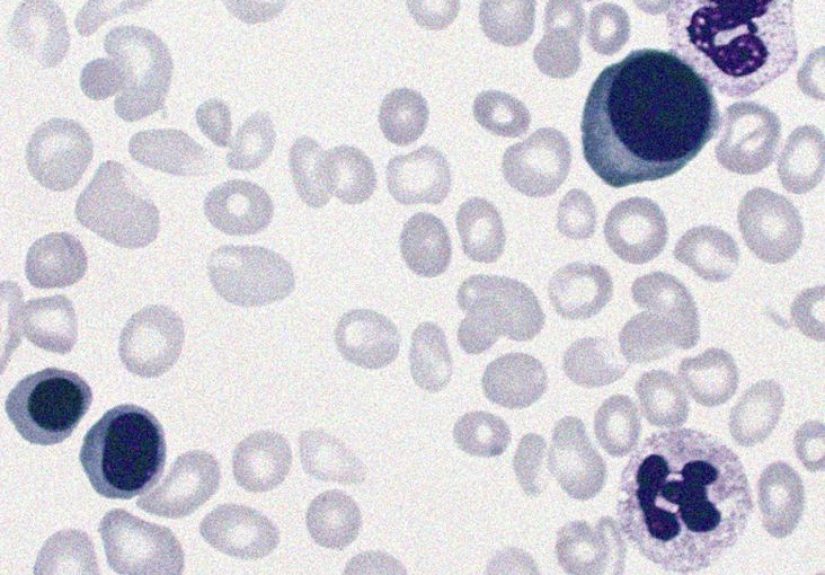

Polycythemia vera is a myeloproliferative neoplasma type of blood cancerwhere the bone marrow makes too many blood cells, especially red blood cells.

Extra red cells make blood thicker and slower-moving, increasing the risk of clots.

Most PV cases are linked to a mutation in JAK2 (a gene involved in blood cell signaling). PV tends to develop slowly and is often found on routine labs

before it causes obvious problems.

How PV can shorten life expectancy (if not controlled)

- Thrombosis (blood clots): The #1 threat. Clots can lead to stroke, heart attack, deep vein thrombosis, or pulmonary embolism.

- Bleeding: Some people have clotting and bleeding tendencies at the same time (yes, the body can be confusing like that).

- Progression: Over many years, PV can progress to post-PV myelofibrosis or, more rarely, transform into acute leukemia.

- Cardiovascular risk: High blood pressure, diabetes, smoking, and high cholesterol can stack the deck against you.

Polycythemia vera life expectancy: What the numbers actually mean

Let’s talk survival in a way that won’t make your brain spiral.

When you see life expectancy stats for PV, you’ll notice they vary. That’s because studies look at different groups: younger vs. older patients,

older vs. newer treatment eras, different risk profiles, and different follow-up lengths.

Typical ranges reported in modern references

-

Median survival is often reported around the mid-teens to ~20 years after diagnosis in many cohorts and summaries.

“Median” means half the people lived longer than that. -

Younger patients often do much better, with some reports showing survival measured in multiple decades (sometimes 30+ years) for those diagnosed

at younger ages. - With consistent care, many people live long livesespecially when clot risk is aggressively managed and other health factors are controlled.

One important note: PV isn’t a stopwatch. Two people can have the same diagnosis and very different outcomes depending on age, clot history, lab control,

cardiovascular risk, and whether symptoms or complications develop over time.

The single most important treatment target: Keep hematocrit under control

If PV had a motto, it would be: “Don’t let the blood get too thick.” Treatment is built around controlling hematocrit

(the percentage of blood made up of red cells).

Why the “less than 45%” hematocrit goal matters

A major clinical trial found that aiming for a hematocrit target of <45% significantly reduced cardiovascular death and major thrombosis compared

with a less strict target. In plain English: tighter control = fewer dangerous clots.

Many clinical references and patient-facing guidelines echo this same approach: maintain hematocrit under 45% (and sometimes even lower targets are suggested for

some patients, depending on clinician judgment).

PV treatment options that can improve prognosis

PV treatment doesn’t just “lower a number.” It lowers the risk of the events that impact life expectancyespecially thrombosis.

Treatment plans are individualized, but most revolve around a few core strategies.

1) Phlebotomy (therapeutic blood draws)

Phlebotomy is exactly what it sounds like: removing blood to quickly reduce red cell mass and hematocrit. It’s often the first-line treatment,

especially for people considered lower risk.

- Upside: Works fast, no chemotherapy, and directly reduces thickness-related risk.

- Downside: Can contribute to iron deficiency and symptoms like fatigue in some people; it also means repeat appointments.

2) Low-dose aspirin

Low-dose aspirin is commonly used (when safe) because it helps reduce clot formation. It’s one of the simplest tools in the PV toolbox,

and it pairs well with hematocrit control.

3) Cytoreductive therapy (medications to lower blood counts)

If you’re at higher risk (often defined by older age and/or a history of thrombosis), or if phlebotomy alone isn’t enough to control counts or symptoms,

clinicians may recommend medication to reduce blood cell production.

Common options include:

- Hydroxyurea: A widely used first-line cytoreductive medication for many higher-risk patients.

- Interferon (including pegylated forms): Often considered for younger patients or specific scenarios; can help control counts and symptoms.

- Ruxolitinib: A targeted therapy option for certain patients, especially when other treatments are not effective or tolerated.

The goal of these medications is still the same: keep blood counts controlled, reduce clot risk, and improve quality of lifebecause living longer is good,

but living longer while feeling miserable is… less ideal.

What influences life expectancy in PV?

Think of PV prognosis as a mix of the disease itself and the “everything else” going on in the body. Some factors aren’t changeable, but many are.

Higher-risk features often discussed in clinical references

- Older age at diagnosis

- History of blood clots

- Higher white blood cell counts (in some prognostic models)

- Cardiovascular risk factors: smoking, uncontrolled hypertension, diabetes, high cholesterol

- Symptoms or progression suggesting more advanced disease behavior

Concrete example: Two different PV “paths”

Example A: A 45-year-old diagnosed on routine bloodwork, no prior clots, no smoking, blood pressure controlled. They do phlebotomy plus aspirin,

keep hematocrit below target, and see hematology regularly. Their biggest job becomes staying consistentlike brushing teeth, but with lab work.

Example B: A 72-year-old with a prior deep vein thrombosis, diabetes, and uncontrolled blood pressure. Their PV is still treatable,

but clot risk is higher. They may need cytoreductive therapy, tighter cardiovascular management, and closer monitoring. Here, outcome hinges on both PV control

and heart-and-vessel risk management.

Does treatment “cure” PV or just manage it?

For most people, PV is considered a chronic condition without a simple cure. The focus is on long-term control.

In selected casesusually when disease progresses significantlymore intensive approaches (including transplant in rare situations) may be considered,

but that’s not the everyday PV story.

The everyday PV story is: keep hematocrit controlled, reduce thrombosis risk, treat symptoms, and monitor for changes over time.

Monitoring: The “maintenance plan” that supports longevity

PV management works best as a long-term partnership with a hematology team. Regular monitoring can catch issues earlybefore complications

become the headline.

Common things clinicians monitor

- Complete blood count (CBC): red cells, white cells, platelets

- Hematocrit trends and phlebotomy needs

- Symptoms like itching (especially after warm showers), headaches, dizziness, fatigue, and night sweats

- Spleen size and abdominal discomfort

- Signs of clotting or bleeding

- Long-term progression markers (if suspected)

Daily-life choices that can protect your prognosis

This is where PV turns into a “small habits, big payoff” condition. Lifestyle isn’t a substitute for medical care, but it can meaningfully reduce the risk

factors that drive complications.

Helpful habits (the boring stuff that works)

- Don’t smoke (or get help quitting if you do).

- Move regularly to support circulationespecially on travel days or long desk days.

- Manage blood pressure, cholesterol, and diabetes like your future self is watching (because they are).

- Stay hydrated unless you’ve been told otherwisedehydration can worsen “thick blood” vibes.

- Know clot warning signs and seek urgent care when appropriate (chest pain, sudden shortness of breath, one-sided weakness, etc.).

Long-term risks: progression to myelofibrosis or leukemia

Most people with PV never experience aggressive transformation, but it’s still part of the conversation because it affects long-range planning.

Over long time horizons, some patients develop post-PV myelofibrosis (bone marrow scarring) or, more rarely, acute myeloid leukemia.

Many references describe long-term risks like thrombosis, post-PV myelofibrosis, and leukemia transformation as possibilities that increase over decades.

The key takeaway isn’t panicit’s follow-up. Monitoring exists so changes can be recognized early.

Frequently asked questions about PV life expectancy

Can someone with PV live a normal lifespan?

Many people with PV live for years or decades after diagnosis, especially with consistent treatment and careful risk-factor management.

“Normal lifespan” depends on age at diagnosis, clot history, cardiovascular health, and how well blood counts stay controlled.

What’s the biggest thing I can do to improve my outlook?

The most consistently emphasized strategy is reducing thrombosis riskusually by maintaining hematocrit under target,

using antiplatelet therapy when appropriate, and controlling cardiovascular risk factors.

Does PV life expectancy change if symptoms are mild?

Mild symptoms can be misleading. Even people who feel fine can have elevated clot risk if hematocrit is high.

That’s why lab control and preventive treatment mattereven when PV feels quiet.

Conclusion: PV prognosis is often about prevention, not prediction

The phrase “polycythemia vera life expectancy” can sound scary, but PV is often a long-haul condition where prevention makes a measurable difference.

The strongest theme across major medical resources is consistent: control hematocrit, reduce clot risk, treat symptoms, and keep up with monitoring.

If you’re living with PV, the goal isn’t to “win” in one heroic moment. It’s to stack small, practical wins over timeregular labs, sticking to the plan,

and taking cardiovascular health seriously. Boring? Sometimes. Effective? Very.

Experiences: What living with PV can feel like (and how people adapt)

When people talk about “life expectancy,” they usually mean yearsbut day-to-day experience matters just as much. PV can be emotionally weird:

you might feel mostly fine, yet the diagnosis comes with the word cancer, lab targets, and a schedule that includes more needles than anyone requested.

Many people describe the first few months as a crash course in learning a new language: hematocrit, phlebotomy, JAK2, platelets, risk categories.

It can feel like you’re studying for an exam you didn’t sign up for.

A common early experience is the “lab number roller coaster.” You get treated, numbers improve, you feel relieved… then a follow-up test shows

hematocrit creeping up again. Over time, many people settle into a rhythm: they learn what “stable” looks like for them and stop treating every lab draw

as a dramatic plot twist. Some patients keep a simple trackerdate, hematocrit, how they felt, whether they had a phlebotomyso they can see patterns

and walk into appointments with confidence instead of questions swirling in their head at 2 a.m.

Then there are symptoms. PV symptoms can be subtle or oddly specific. A classic one is itching, sometimes triggered by warm showers.

People often experiment with small changeslukewarm water, gentle cleansers, moisturizing routines, and clinician-recommended optionsuntil they find a combo

that makes showering feel normal again. Fatigue can also be part of the picture, especially for those who need frequent phlebotomies and develop low iron.

Many patients describe fatigue as “not sleepy, just drained.” Practical coping tends to look like pacing, protecting sleep, and talking openly with the care team

about whether treatment adjustments or symptom-focused strategies are needed.

Emotionally, PV can push people into two extremes: constant worry or complete denial. A healthier middle ground often develops with time:

“I’m taking this seriously, but I’m not letting it eat my whole life.” Support can helpwhether that’s a partner who learns the warning signs of clots,

a friend who drives you to an appointment, or an online community where people trade real-world tips (like what to bring to a long clinic visit).

It’s also common to feel frustrated that you have to think about stroke prevention while everyone else is arguing about what to watch on Netflix.

But many people eventually find that PV nudges them into better health habitsmoving more, quitting smoking, keeping blood pressure controlledbecause the “why”

becomes very real.

One of the most empowering experiences for many patients is realizing that PV management is not just about avoiding bad outcomesit’s about building a stable,

predictable life. You learn to plan around appointments, travel smarter (move often, hydrate, talk to your clinician if you have specific risks),

and treat follow-ups as routine maintenance rather than a crisis signal. Over time, PV can become less like a thunderstorm over your head and more like a

weather app notification: something you check, manage, and move forward with. And that’s the pointgood PV care aims to protect both your longevity

and your everyday life.