Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- What Is Prader-Willi Syndrome?

- Symptoms of Prader-Willi Syndrome (By Life Stage)

- What Causes Prader-Willi Syndrome?

- How Prader-Willi Syndrome Is Diagnosed

- Treatments for Prader-Willi Syndrome

- Nutrition and weight management: the foundation

- Growth hormone therapy: more than height

- Hormone support and bone health

- Developmental therapies and education supports

- Behavioral and mental health treatment

- Sleep, breathing, and other medical monitoring

- Medication options for hyperphagia: a major update

- Living With Prader-Willi Syndrome: What “Good Support” Looks Like

- When to Talk to a Doctor

- Conclusion

- Experiences: What Life With Prader-Willi Syndrome Can Feel Like (500+ Words)

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS) is one of those conditions that can feel like a plot twist written into someone’s DNAbecause, in a way, it is.

It’s a rare genetic disorder that affects appetite, growth, metabolism, behavior, and learning. And it has a very specific “timeline”:

early life often starts with low muscle tone and feeding trouble, while later childhood can bring the hallmark symptomhyperphagia, an intense, persistent drive to eat.

That swing from “hard to feed” to “never feels full” is part of what makes PWS so challenging for families and care teams.

The good news (yes, there’s good news): early diagnosis and modern, proactive care can dramatically improve health and quality of life.

This article breaks down PWS symptoms by age, explains what causes it, and walks through treatmentsboth the everyday strategies that matter most and the medical therapies that can help.

What Is Prader-Willi Syndrome?

Prader-Willi syndrome is a genetic imprinting disorder caused by the loss of expression of certain genes that are normally active on the paternal copy of chromosome 15

(specifically the 15q11.2–q13 region). “Imprinting” is basically the body’s way of saying, “This gene should be read from Mom’s copy” or “This one should be read from Dad’s copy.”

In PWS, the body is missing the working “Dad” instructions for key genes in that regionso the brain and body systems those genes influence don’t develop or function typically.

PWS affects multiple systems, but it often centers around hypothalamic function (the hypothalamus helps regulate hunger, hormones, temperature, sleep, and more).

That’s why PWS isn’t only about appetiteit can also involve short stature, delayed puberty, low muscle tone, sleep issues, and behavioral challenges.

Symptoms of Prader-Willi Syndrome (By Life Stage)

Infancy: “Floppy baby,” weak feeding, slow growth

In the first months of life, PWS often shows up as significant hypotonia (low muscle tone). Babies may seem “floppy,” have a weak cry,

and struggle with sucking and swallowing. Feeding can be difficultsome infants need specialized nipples, feeding therapy, or temporary tube feeding to get enough calories.

Because intake is low and muscle tone is reduced, babies may gain weight slowly and miss early growth milestones.

Other early signs can include sleepiness, decreased movement, and delayed motor development (rolling, sitting, crawling).

A clinician may suspect PWS when low muscle tone and feeding difficulty appear togetherespecially if there are also subtle physical features like a narrow forehead or almond-shaped eyes.

Toddler and preschool years: tone improves, appetite begins to change

Many children with PWS gradually gain strength and do better with feeding as they get older.

But around the toddler years (timing varies), appetite patterns may begin shifting. Some kids move from “picky or low appetite” into a phase of

increasing interest in food. This may look like asking about meals more often, focusing on snacks, or becoming upset when food routines change.

At the same time, developmental delays may become more noticeable. Speech therapy, occupational therapy, and early intervention services can be especially helpful here.

Childhood: hyperphagia and rapid weight gain risk

The most widely recognized feature of PWS is hyperphagiaan intense drive to eat paired with reduced satiety (not feeling full).

Without structured supports, hyperphagia can lead to chronic overeating and significant obesity.

Importantly, this is not “just being hungry” in the everyday sense. It can include food seeking behaviors, preoccupation with meal timing,

anxiety around food, and in some cases, sneaking or hoarding food.

Weight gain can happen even with calorie amounts that might not cause obesity in other children, partly due to differences in body composition, metabolism, and activity.

This is why PWS care often focuses on environmental controls and consistent routinesnot because anyone is being strict for fun, but because it’s medically necessary.

Teens and adults: hormone issues, ongoing appetite management, and health monitoring

In adolescence, many individuals with PWS have hypogonadism (underdevelopment of sex hormones), which may cause delayed or incomplete puberty.

Adults may face infertility, low bone density risk, and reduced muscle mass if hormone deficiencies aren’t addressed.

Ongoing challenges can include behavioral rigidity, skin picking, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive-like tendencies, and difficulty with emotional regulation.

Sleep disorders (including sleep apnea) can also occur and should be evaluatedespecially because untreated sleep issues can affect behavior, attention, and weight.

Common symptoms across ages

- Low muscle tone and reduced muscle mass

- Short stature (often related to growth hormone deficiency and other endocrine factors)

- Hyperphagia and obesity risk

- Developmental delays and mild-to-moderate learning differences

- Behavioral challenges (tantrums, rigidity, compulsive behaviors, skin picking)

- Hormone deficiencies (hypogonadism; sometimes thyroid/adrenal concerns are evaluated)

- Sleep problems (sleep apnea, excessive daytime sleepiness in some individuals)

What Causes Prader-Willi Syndrome?

PWS happens when genes that should be active on the paternal copy of chromosome 15 (15q11.2–q13) are not expressed.

The “why” usually falls into one of a few genetic mechanisms:

1) Paternal deletion (most common)

In many cases, a segment of the paternal chromosome 15 is missing (deleted). If the key region is gone, the paternal genes that should be “on” in that area aren’t available.

2) Maternal uniparental disomy (UPD) 15

Sometimes a child inherits two copies of chromosome 15 from the mother and none from the father in that region.

Because those genes are imprinted, having “two mom copies” still doesn’t replace the missing paternal gene expression.

3) Imprinting defects

In imprinting defects, the chromosome may be present, but the gene “on/off” marking is wrongso paternal genes that should be active are silenced.

Most cases are not inherited in a predictable family pattern and occur as a genetic event during conception or early development.

However, understanding the specific mechanism can help with genetic counseling and recurrence risk discussions for families.

How Prader-Willi Syndrome Is Diagnosed

While symptoms may raise suspicion, the diagnosis is confirmed through genetic testing.

The cornerstone test is usually a DNA methylation analysis, which can detect the abnormal imprinting pattern seen in PWS.

If methylation testing indicates PWS, additional testing (such as microarray or other studies) may be done to determine whether the cause is a deletion, maternal UPD, or an imprinting defect.

Earlier diagnosis is valuable because early interventionsespecially nutrition support in infancy and proactive therapies for growth and developmentcan improve outcomes.

If a newborn has significant hypotonia and feeding difficulty, clinicians may recommend testing sooner rather than later.

Treatments for Prader-Willi Syndrome

There’s no single “cure” for PWS, but there is a clear reality: good treatment is a long-term team sport.

Most effective care is multidisciplinary, often involving pediatrics, endocrinology, nutrition, sleep medicine, developmental specialists,

behavioral health, physical/occupational/speech therapy, andover timetransition planning for adulthood.

Nutrition and weight management: the foundation

Because hyperphagia can be relentless and metabolism may be different, many individuals with PWS need a carefully structured eating plan.

The goal is not “diet culture” or restriction for appearanceit’s medical safety.

Practical strategies often include:

- Predictable meal and snack schedules (reduces anxiety and bargaining)

- Portion-controlled, nutrient-dense foods (lean proteins, fiber-rich produce, whole grains as tolerated)

- Limiting easy access to extra food (food-secure environment, supervision as needed)

- Consistent rules across caregivers (mixed messages can backfire)

- Regular activity designed for ability level (supports muscle mass, mood, and health)

Many families find it helps to treat food routines like a “house policy,” not a daily negotiation.

That can sound strictuntil you realize it often reduces conflict and increases a child’s sense of predictability.

Growth hormone therapy: more than height

Recombinant human growth hormone (GH) is widely used in children with PWS and may improve body composition (more lean mass, less fat mass),

support linear growth, and help with physical strength and motor development. GH therapy is typically managed by a pediatric endocrinologist,

with careful monitoring (including growth patterns, IGF-1 levels, and screening for sleep-disordered breathing when appropriate).

GH therapy isn’t a “one-size-fits-all,” and it doesn’t replace food managementbut it can be a major quality-of-life tool when appropriately prescribed and monitored.

Hormone support and bone health

Because hypogonadism is common, some teens and adults benefit from sex hormone replacement to support puberty-related development, bone density, and overall health.

Clinicians may also monitor thyroid function and other endocrine concerns depending on symptoms and individual risk.

Bone health matters: lower muscle mass, hormone differences, and reduced activity can raise fracture risk over time, so screening and prevention strategies may be discussed.

Developmental therapies and education supports

Early intervention often includes:

- Physical therapy for hypotonia and gross motor skills

- Occupational therapy for fine motor skills and daily living tasks

- Speech-language therapy for speech, feeding support, and communication skills

- Individualized education plans (IEPs) or school accommodations when needed

These supports can be especially powerful when started earlybefore school challenges and frustration have time to snowball.

Behavioral and mental health treatment

Behavioral features in PWS often respond best to a combination of structure, skills training, and targeted clinical support.

Helpful approaches may include:

- Clear routines and advance warnings before transitions

- Behavioral therapy to build coping skills and reduce explosive episodes

- Support for anxiety (therapy, school supports, and sometimes medication when clinically appropriate)

- Strategies for skin picking (habit reversal approaches, protective measures, treating underlying anxiety)

A practical tip many families use: when emotions rise, simplify language and choices. Too many options can feel like a pop quiz during a fire drill.

Sleep, breathing, and other medical monitoring

Because sleep-disordered breathing can occur in PWS, clinicians may recommend sleep studies if symptoms suggest sleep apnea (snoring, daytime sleepiness, behavior changes).

Monitoring also commonly includes screening for obesity-related complications such as type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure, and lipid issuesespecially in adolescence and adulthood.

Orthopedic issues like scoliosis may also need evaluation.

Medication options for hyperphagia: a major update

For years, treatment focused on behavioral and environmental strategies because no medication was specifically approved to treat hyperphagia in PWS.

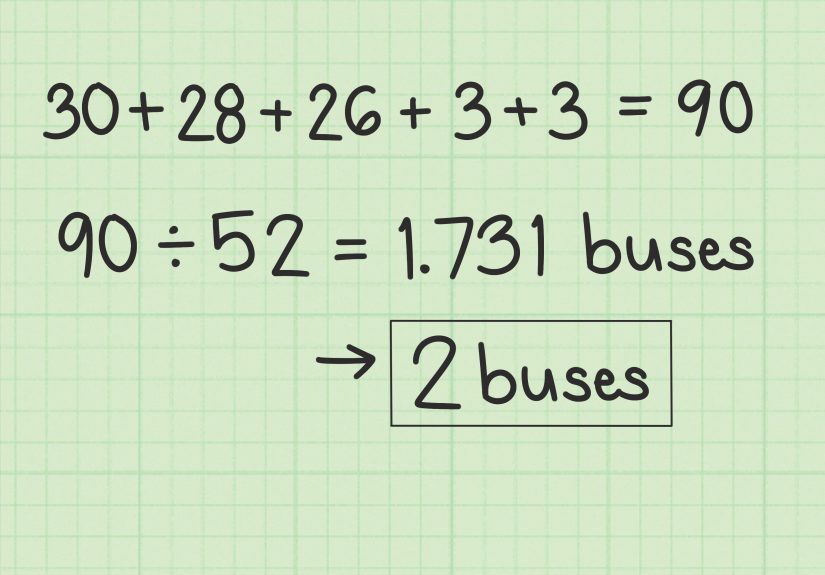

Recently, the U.S. FDA approved VYKAT XR (diazoxide choline) extended-release tablets for the treatment of hyperphagia in

adults and pediatric patients ages 4 years and older with Prader-Willi syndrome.

This is a meaningful milestonethough it’s still only one part of care and does not replace nutrition plans, supervision, and multidisciplinary support.

If you’re considering medication therapy, it’s essential to discuss benefits, risks, and monitoring with a specialist experienced in PWS.

Treatment decisions should be individualized, taking into account medical history, sleep concerns, metabolic risks, and family goals.

Living With Prader-Willi Syndrome: What “Good Support” Looks Like

PWS management is often most successful when it’s proactive rather than reactive.

Many families and adults with PWS describe the biggest wins as the boring-but-mighty stuff:

consistent routines, clear rules around food, supportive schools, regular medical follow-up, and a community that understands the condition.

Transition planning matters too. As children become teens, goals often shift toward building life skills: safe independence, vocational planning, social support,

and finding adult medical providers who understand rare genetic conditions and obesity-related risks.

When to Talk to a Doctor

Consider asking a clinician about PWS if an infant has pronounced hypotonia and feeding difficultyespecially if growth is slow and milestones are delayed.

In older children, a strong and escalating preoccupation with food plus rapid weight gain, short stature, and developmental/behavioral patterns may also raise suspicion.

Genetic testing can clarify the diagnosis and help guide next steps.

Conclusion

Prader-Willi syndrome is a complex condition, but it’s not a mystery box with no instructions.

We understand the genetic cause, we know the signature symptom patterns, and we have proven strategies that can improve health outcomes.

The most effective treatment blends practical daily supports (food structure, routine, activity, education plans) with medical care (growth hormone therapy,

hormone support, sleep evaluation, and monitoring for complications).

With early diagnosis, consistent support, and the right medical team, many people with PWS make meaningful progress in physical health, learning, and daily functioning

and families can move from constant crisis management to a more stable, predictable life.

Experiences: What Life With Prader-Willi Syndrome Can Feel Like (500+ Words)

If you ask caregivers what surprised them most about Prader-Willi syndrome, many will tell you it’s the dramatic shift over time. In early infancy,

the worry is often: “How do we get enough calories in?” Feeding can feel like a full-time jobspecial bottles, slow feeds, frequent appointments,

and the emotional strain of watching a baby struggle to gain weight. Parents may describe feeling stuck between exhaustion and vigilance, celebrating

small wins like a stronger suck or a few extra ounces gained.

Then, later, the story can flip. Families often describe a gradual change from “not interested in food” to “food is the main topic of conversation.”

At first it might be subtlemore questions about what’s for dinner, asking for seconds, getting upset if snack time runs late. But for many,

hyperphagia becomes a constant presence. Caregivers sometimes compare it to having a “smoke alarm” that never stops beepingexcept the alarm is hunger,

and the person experiencing it can’t simply ignore it or reason it away.

This is where the practical reality of PWS can become emotionally complicated. Food security measureslocking pantries, supervising kitchens,

controlling access at school or during partiesmay look harsh from the outside. Inside the home, families often describe them as safety equipment,

like child locks on cleaning supplies. The goal isn’t punishment. It’s prevention: preventing dangerous overeating, preventing conflict fueled by constant temptation,

and preventing the medical complications that can follow uncontrolled weight gain.

Daily life often becomes a balancing act between structure and dignity. Many caregivers learn that predictability reduces anxiety:

meals happen at the same times, portions are consistent, and rules don’t change based on who is tired, who feels guilty, or who wants to avoid a meltdown.

When expectations are steady, some families report fewer battlesnot because hyperphagia disappears, but because the environment is less triggering.

Over time, people with PWS may also learn coping tools: distraction strategies, scheduled activities right after meals, and calming routines

that help when the “food thoughts” get loud.

School can be another layer. Families often advocate for accommodations that go beyond academics:

supervising food access, planning for classroom celebrations, and building behavior supports around transitions.

Some students thrive with clear visual schedules and short, concrete instructions. Others need help with emotional regulation,

especially when plans change unexpectedly. Teachers and staff who understand that certain behaviors are part of a neurogenetic conditionnot “bad attitude”

can make a huge difference in a child’s confidence and social inclusion.

Medical care can feel like a long road, but many families report that certain interventions change the day-to-day in tangible ways.

Growth hormone therapy, for example, is often described as more than “getting taller”it can improve strength and endurance,

which may open doors for sports, play, and independence. Support for sleep problems can improve mood and attention.

Behavioral therapy can help families trade constant firefighting for practical skills and routines.

And newer medication options aimed at hyperphagia represent hope for reducing the intensity of food drive for some individuals

though families still emphasize that medication is rarely “the whole answer.”

In adulthood, families and individuals often focus on safe independence: supportive living settings, employment programs,

community activities, and health monitoring that continues long after pediatric care ends. Many families say their best moments come

from building a life that’s bigger than the diagnosiscelebrating friendships, hobbies, work achievements, and routines that create stability.

PWS can be demanding, but with the right supports, people can still build meaningful, connected livesone structured day at a time.