Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

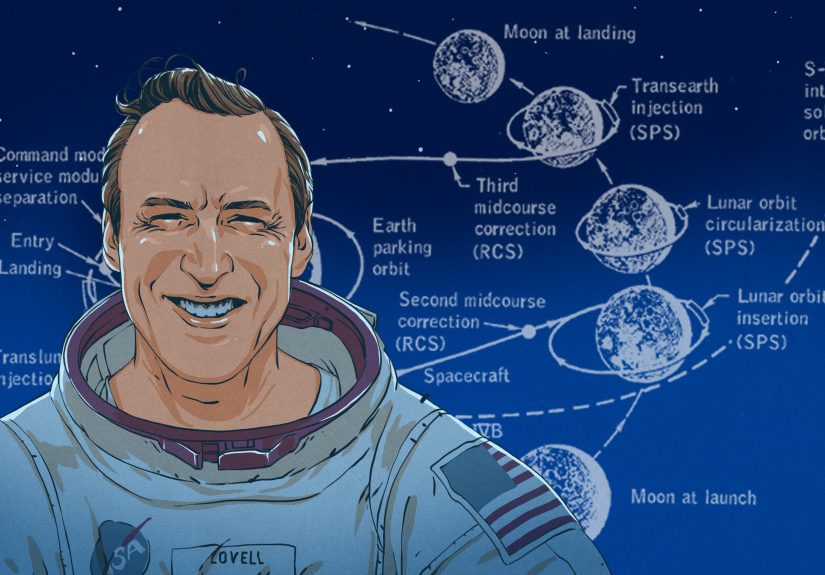

If you were designing a movie about a commander who literally flies away from an explosion in deep space and still brings everyone home, you’d probably be told to tone it down. Yet that is exactly what James “Jim” Lovell did on Apollo 13 – 200,000 miles from Earth, with a crippled spacecraft, dwindling power, and no second chances.

Lovell’s story has everything: near disaster, absurdly clever engineering, and a leader whose calm voice made “Houston, we’ve had a problem” sound like a weather update instead of a life-or-death alarm. He’s the archetype for what Hackaday fans love – someone who treats impossible problems like an invitation to build a better workaround.

As we remember James Lovell – especially after his passing in 2025 at age 97 – it’s worth looking beyond the movie lines and the hero headlines. Who was this man who cheated death in space, and what can the rest of us learn from the way he thought, worked, and led?

From Model Rockets to the Moon

James Lovell was born in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1928 and grew up in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the kind of kid who thought rocket design manuals were light reading. He studied at the U.S. Naval Academy, became a Navy pilot, and eventually a test pilot – the closest thing Earth has to a training program for “future astronaut.”

When NASA picked him in 1962 as part of the “Next Nine” astronaut group – the same class that included Neil Armstrong – Lovell arrived with a reputation: technically sharp, steady under pressure, and almost annoyingly unflappable. He wasn’t the loudest guy in the room, but when things got complicated, people tended to look in his direction.

Before Lovell ever saw the Moon up close, he logged a lot of prep time in low Earth orbit. His flights on Gemini 7 and Gemini 12 were the space-age equivalent of a systems stress test: long-duration missions, rendezvous, docking, and learning how humans actually function when they’re stuck in a small can for days or weeks.

Gemini: Practicing for the Unknown

Gemini 7: Two Weeks in a Very Small Office

Gemini 7 launched in December 1965 with Lovell and commander Frank Borman squeezed into a spacecraft about the size of a compact car’s interior. Their mission: stay in orbit for nearly 14 days and serve as the passive partner in the first rendezvous with another crewed spacecraft, Gemini 6.

There was no glamor in Gemini 7, just relentless data-gathering: heart rate, muscle loss, bone density, cabin procedures, and psychological strain. At one point, the highlight of their day was simply having another spacecraft pull up to say hello. But the mission proved humans could survive in space long enough for a trip to the Moon and back – a prerequisite for everything Apollo would later attempt.

Gemini 12: Docking, Spacewalks, and a Future Moon Walker

Lovell returned to space in 1966 as commander of Gemini 12, flying with Buzz Aldrin. The goals this time were docking with an Agena target vehicle and finally getting spacewalk procedures under control. Earlier Gemini EVAs had gone badly – astronauts overheated and exhausted themselves wrestling with tools in microgravity.

With carefully planned handholds and tasks, Gemini 12 proved that humans could work effectively outside a spacecraft. That experience fed directly into Apollo’s lunar missions. Lovell wasn’t just a guy who “got lucky” on Apollo 13 – he helped debug the entire playbook for working in space.

Around the Moon Before Anyone Landed: Apollo 8

In December 1968, Lovell boarded Apollo 8 with Frank Borman and Bill Anders for what became one of the boldest reconfigurations of a mission in NASA history. Originally planned as an Earth-orbit test, Apollo 8 was re-tasked – on surprisingly short notice – to become the first crewed flight to orbit the Moon, leapfrogging several intermediate steps.

Apollo 8’s Saturn V launch was the first time humans rode that massive rocket into space, and their Christmas Eve broadcast from lunar orbit – reading from the Book of Genesis while Earth hung in the window – became iconic. It was also Lovell’s first close-up look at the Moon’s surface, a reconnaissance mission that would later guide Apollo 13’s planned landing site.

That flight gave Lovell something precious: deep familiarity with lunar navigation and how the spacecraft behaved when it was a quarter-million miles from home. When things went wrong on Apollo 13, he’d already navigated a path around the Moon once. That prior experience would matter more than anyone realized.

A “Successful Failure”: The Apollo 13 Crisis

Apollo 13, launched in April 1970, was supposed to be Lovell’s grand finale: his second trip to the Moon and his first chance to walk on it. Instead, it became a masterclass in emergency engineering.

About 56 hours into the flight, an oxygen tank in the service module exploded. Lights flickered, warning alarms blared, and the spacecraft suddenly lost much of its power and life support. Sitting in the command module, Jack Swigert reported, “Okay, Houston, we’ve had a problem here.” Lovell followed up moments later: “Houston, we’ve had a problem.”

The damage crippled the command module. To survive, Lovell, Swigert, and Fred Haise had to shut almost everything down and retreat into the lunar module – a vehicle designed to support two astronauts for a few days on the Moon, not three astronauts all the way home. Temperatures dropped, drinking water had to be rationed, and every watt of power became precious.

Under Lovell’s command, the crew worked with Mission Control to improvise a new flight plan: swing around the far side of the Moon and return to Earth on a free-return trajectory. Plus, they had to build a makeshift adapter to fit square command-module carbon dioxide scrubber cartridges into the lunar module’s round sockets, using items like suit hoses, plastic covers, and tape – the now-legendary “mailbox” fix.

The mission never landed on the Moon, but the crew splashed down safely in the Pacific four days later. NASA would later call Apollo 13 a “successful failure” – the kind of phrase only an engineer could love, describing a mission that didn’t meet its original goal yet generated priceless data and proved that human ingenuity can outmaneuver catastrophe.

“Houston, We’ve Had a Problem”: The Quote vs. the Myth

The most famous line from Apollo 13 – “Houston, we have a problem” – isn’t what was actually said. The real words, from Swigert and then Lovell, used the past tense: “we’ve had a problem.” The difference sounds minor, but it matters to history buffs and audio purists.

The movie Apollo 13 polished the phrase into “Houston, we have a problem” because it sounded cleaner and more dramatic, and because by 1995 the line had already taken on a life of its own in pop culture. It joined “One small step” as one of the defining sound bites of the space age, a tiny example of how reality and storytelling intertwine when we talk about big technical feats.

Cheating Death, Engineering-Style

What made Lovell “the man who cheated death in space” wasn’t luck. It was how he and his team thought. Faced with a failing spacecraft, they didn’t treat the systems as sacred. They treated them as components: power budgets, thermal constraints, oxygen partial pressure, guidance margins. They looked at the problem like hackers taking apart a device on the bench, asking, “What else can this do?”

The lunar module became a lifeboat. Equipment meant for the surface of the Moon became emergency supplies. Checklists were rewritten on the fly. Maneuvers were calculated with slide rules and quick mental math when onboard computers had to stay mostly powered down. The crew, flight controllers, and engineers turned an almost certain fatal failure into something survivable by reimagining their tools in real time.

Lovell was the voice tying all of this together – firm but calm, relentlessly focused on the next step instead of the odds. He didn’t need to sound brave. He just needed to sound steady, and he did. In interviews later, he shrugged off the idea that he was a hero, pointing instead to the hundreds of people on the ground who solved problems right alongside him.

Life After Splashdown

After Apollo 13, Lovell never flew in space again. He retired from the Navy and NASA in 1973 and moved into the business world, including leadership roles in the energy and telecommunications sectors. He also stayed deeply connected to space exploration as a public speaker and as a trustee of science institutions such as Chicago’s Adler Planetarium.

In 1994, he co-wrote Lost Moon with journalist Jeffrey Kluger, a detailed, inside-the-loop account of the Apollo 13 mission. The book became the basis for Ron Howard’s 1995 film Apollo 13. Tom Hanks portrayed Lovell on screen, but Lovell himself made a brief cameo as the captain of the recovery ship USS Iwo Jima. When the filmmakers offered to promote his character to admiral for dramatic effect, he reportedly refused – he’d retired as a captain in the Navy, and a captain he would remain.

The public never stopped seeing him as a hero, but Lovell seemed more amused than impressed by his own fame. At events, he would joke that audiences expecting Tom Hanks were stuck instead with “little old me.” Yet his impact was taken seriously: he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom and later the Congressional Space Medal of Honor, among many other awards.

When Lovell died in August 2025 at age 97, tributes poured in from NASA, fellow astronauts, and fans around the world. Tom Hanks called him a daring leader and an explorer whose courage made it easier for others to dream big. NASA emphasized his “calm strength under pressure” and how his legacy still echoes in modern missions that trace their lineage back to Apollo.

Why James Lovell Still Matters

Lovell’s story resonates today because it isn’t just about space hardware. It’s about how people behave when everything falls apart. For engineers, makers, and anyone who has stared down a blinking error light at 3 a.m., Apollo 13 feels oddly familiar. It’s just that most of us don’t have the Moon outside the window when things go wrong.

Three themes from Lovell’s life stand out:

- Preparation quietly pays off. His years flying test aircraft, sitting in cramped Gemini capsules, and navigating around the Moon on Apollo 8 gave him a deep mental model of how systems behaved under stress. When the oxygen tank blew, he wasn’t improvising from scratch – he was remixing everything he already knew.

- Calm is contagious. Lovell’s tone on the radio helped keep the crew and flight controllers focused on tasks instead of outcomes. In any crisis, someone’s emotional state is going to set the default. Lovell made sure that default was “steady,” not “panicked.”

- Teams beat heroes. Lovell never pretended he saved Apollo 13 single-handedly. He was honest about the fact that hundreds of engineers in Houston, and decades of prior testing, created the conditions for success. That humility is itself a kind of leadership.

Those lessons translate far beyond spaceflight. Whether you’re designing open-source hardware, tuning a control system in your garage lab, or just troubleshooting a server that picked the worst possible time to crash, Lovell’s approach – know your system deeply, stay calm, and lean on your team – is worth copying.

Experiences and Reflections Inspired by Lovell’s “Successful Failure”

You don’t need to strap into a Saturn V to have your own “Apollo 13 moment.” Most of us will never see the inside of a spacecraft, but we’ve all been in situations where the plan exploded, the deadline stayed put, and the resources suddenly shrank. That’s where Lovell’s story becomes more than space history – it becomes a kind of user manual for real life.

Your “Oxygen Tank Just Blew” Moment

Think about a project where something failed at exactly the wrong time: a prototype that died in front of investors, a critical dataset that corrupted the night before launch, or a production system that went down during peak traffic. In those moments, it’s tempting to freeze or flail. Lovell reminds us that the first step is not magic – it’s assessment. On Apollo 13, the crew didn’t immediately start flipping switches at random. They verified what still worked, what didn’t, and what could be repurposed.

Applied to everyday work, that looks like pulling logs, mapping dependencies, and ruthlessly separating symptoms from causes. Instead of asking, “How doomed are we?” the Lovell-style question is, “What do we actually know, and what can we still use?”

Turning the Lunar Module into a Lifeboat – and Your Tools into Swiss Army Knives

One of the most memorable parts of Apollo 13 is how the lunar module – designed for Moon landings – became an emergency shelter and propulsion system. Nothing about its original spec sheet said, “Supports three people all the way home,” but with creative procedures and tight rationing, that’s exactly what it did.

In more down-to-Earth settings, we do similar things all the time: reusing test rigs as temporary production hardware, turning a 3D printer into a parts factory during a supply chain crunch, or repurposing consumer gear for lab experiments. Lovell’s experience encourages us to be more deliberate about that mindset. When you design or buy tools, you’re not just getting what’s on the label – you’re acquiring potential future lifeboats. Thinking ahead about “secondary uses” can make you far more resilient when failure hits.

Leading When Everyone’s Tired and Cold

The Apollo 13 crew spent days in a freezing cabin, exhausted and dehydrated, sleeping in shifts. Yet the mission needed precise manual burns and careful checklist execution to have any chance of success. That meant Lovell had to balance compassion – acknowledging his crew’s physical limits – with the harsh reality that mistakes could be fatal.

Most managers will never face stakes that high (thankfully), but we do lead people who are tired, stressed, or scared they’re about to fail. Lovell’s example shows that leadership isn’t about pretending things are fine; it’s about communicating clearly, sharing the load, and narrowing focus to the next actionable step. “Here’s what we do for the next 10 minutes” beats “Everything will be okay” every time.

Embracing the “Successful Failure” Mindset

Finally, there’s the idea that Apollo 13 was a “successful failure.” That attitude is incredibly useful in engineering, where a project can miss its original target but still generate valuable knowledge. Lovell never got to walk on the Moon. He admitted that was his one big regret. But he also recognized that the mission pushed spacecraft design, operations, and safety protocols forward in ways that protected later crews.

Translated to a lab, workshop, or startup, this means documenting your misfires instead of burying them, running postmortems that are more curious than blameful, and asking, “What did we learn here that’s worth more than what we lost?” If you can honestly answer that question, your own near-disasters may, like Lovell’s, eventually become the stories you’re proudest to tell.

Remembering James Lovell, then, is not just about honoring an Apollo 13 commander or a NASA legend. It’s about adopting a way of thinking: deeply prepared, quietly confident, relentlessly collaborative, and just optimistic enough to believe that even when an oxygen tank explodes – literally or metaphorically – there is almost always a path home if you’re willing to look for it.