Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Why “deadly hypotheses” keep coming back

- The Seven Deadly Medical Hypotheses, revisited

- 1) “You don’t need a hypothesisand any method is fine as long as the data look exciting.”

- 2) “Estrogen is a carcinogen, so hormone replacement therapy inevitably causes breast cancer.”

- 3) “Megavitamin therapy is beneficialand harmlessso why not take more?”

- 4) “Screening tests beyond the standard exam are always a big win for healthy adults.”

- 5) “You can prevent cancer primarily by manipulating nutrition.”

- 6) “Personalized medicine will reacquaint us with the ‘cure for cancer’any day now.”

- 7) “Cancer chemotherapy is a major public health advance (full stop).”

- So what do we do with this list in 2026?

- Experiences from the real world (about )

- Conclusion

- SEO Tags

Medicine has a talent for doing two things at once: saving lives and making confident predictions that later

need to be walked back in sensible shoes. That’s not a flawit’s the whole deal. We learn, we revise, we

replace yesterday’s “obvious” with today’s “actually…”.

The phrase “Seven Deadly Medical Hypotheses” comes from a skeptical tradition of calling out

popular ideas that sound scientific, attract funding or headlines, and then underperform when tested in the

real world. “Deadly” here isn’t meant as melodrama; it’s shorthand for hypotheses that can waste time,

misdirect research, encourage low-value care, or distort public understanding of what good evidence looks like.

Revisiting the seven today is useful because the incentives that created them haven’t disappeared. In fact,

modern toolsbig-data analytics, genome-scale profiling, and social-media-speed hypecan amplify the same

mistakes. The goal of this article is not to dunk on science (science does that to itself eventually). The goal

is to turn these seven cautionary tales into a practical “spot the problem early” checklist for readers, writers,

and anyone who’s ever forwarded a “breakthrough” article at 1 a.m.

Why “deadly hypotheses” keep coming back

A hypothesis becomes “deadly” when it’s both (1) emotionally satisfying and (2) weakly protected from

disconfirmation. The most dangerous ideas often have a few common traits:

- They’re plausible-sounding (often because they’re partly true in a narrow context).

- They’re hard to test cleanly (lots of confounders, fuzzy outcomes, or long timelines).

- They’re easy to market (“personalized,” “natural,” “early detection,” “miracle vitamin”).

- They invite overgeneralization from lab findings to human outcomes.

With that in mind, let’s revisit the sevenwhat they claimed, why people believed them, what evidence has

actually shown, and what a more evidence-friendly version looks like.

The Seven Deadly Medical Hypotheses, revisited

1) “You don’t need a hypothesisand any method is fine as long as the data look exciting.”

In modern terms, this is the temptation to treat exploratory research as if it were confirmatory proof.

Exploration is not the villainmedicine needs discovery science. The problem starts when we confuse

finding signals with proving causes.

Big datasets (electronic health records, biobanks, omics, wearables) can surface patterns no human would spot.

But patterns are easy to “discover” when you run enough comparisons. Without careful design, you can

generate a parade of results that fail to replicate, don’t generalize, or vanish when confounding is addressed.

What “revisited” looks like now: We’re better than we used to be about guardrailspre-registration,

replication cohorts, transparent reporting, and more rigorous statistical standards in some fields. Yet the

incentives still reward novelty. The healthier framing is:

exploratory studies generate hypotheses; randomized trials and high-quality causal methods test them.

Specific example: A genome-wide association study might find a genetic variant linked with a disease.

That’s not a treatment plan. It’s a clueone that may be biologically informative but clinically irrelevant unless

it points to a modifiable pathway and leads to interventions that improve outcomes.

2) “Estrogen is a carcinogen, so hormone replacement therapy inevitably causes breast cancer.”

This hypothesis is a classic case of “true-ish, but dangerously incomplete.” Estrogen can influence breast

tissue biology, and some hormone therapy regimens are associated with increased breast cancer risk. But the

risk is not one-size-fits-all, and the details matter: type of therapy, timing,

duration, and individual risk factors.

Large studies (including major randomized trial evidence) reshaped the conversation by showing that

combined estrogen-plus-progestin therapy is linked with increased breast cancer incidence, while other

regimens (such as estrogen-alone in specific populations) can show different risk profiles. That doesn’t mean

“HRT is safe for everyone,” and it doesn’t mean “HRT is poison.” It means medical decisions should be made

with specifics, not slogans.

What “revisited” looks like now: The modern consensus is more practical than dramatic:

menopausal hormone therapy can be appropriate for symptom relief in some people, at certain ages, with

individualized risk assessmentand it should not be treated as a universal long-term prevention strategy for

chronic disease.

Good takeaway: If an article says “X causes cancer” but doesn’t specify dose, formulation, baseline

risk, absolute risk change, and the population studied, you’re reading a headline, not evidence.

3) “Megavitamin therapy is beneficialand harmlessso why not take more?”

Vitamins are essential. That’s why deficiency states are real and serious. But “essential” does not mean

“more is better,” and “natural” does not mean “risk-free.”

Supplement mega-dosing has repeatedly stumbled on the same rake: biology is not impressed by marketing.

Some large trials have shown no benefit for preventing major outcomes, and certain supplements (especially

in high-risk groups like smokers) have been associated with harms. Also, supplements can interact with

medications, and product quality can vary.

What “revisited” looks like now: Evidence-based guidance increasingly distinguishes between

(1) correcting deficiencies or treating specific conditions, and (2) taking supplements “just in case” to prevent

chronic disease in well-nourished adults. A sensible version of the hypothesis is:

supplement when there’s a clear indication, evidence of benefit, and an understood risk profile.

Practical rule: If the pitch is “one pill covers everything,” demand outcome dataactual reductions in

disease or death, not just changes in lab values.

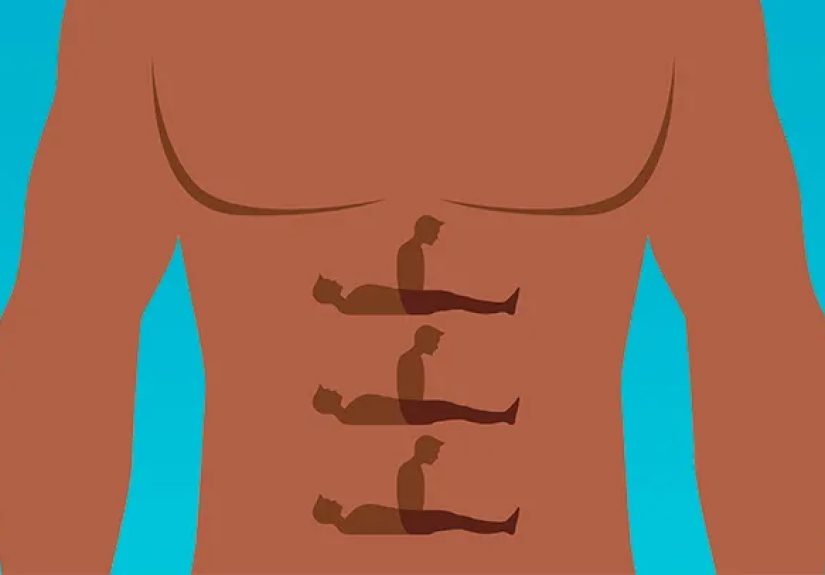

4) “Screening tests beyond the standard exam are always a big win for healthy adults.”

Screening feels like a moral good: find disease early, save lives, high-five everyone. Sometimes that’s true.

But screening has a shadow side: false positives, unnecessary biopsies, overdiagnosis (finding problems that

would never cause harm), and overtreatment.

The “revisited” lesson is that screening is not a generic virtue; it’s a tradeoff. The right question is not

“Should we screen?” but:

Who benefits, by how much, and what harms are acceptable?

Modern preventive medicine leans on risk-stratified, evidence-rated recommendations rather than

“more testing for everyone.” In many areas, guidelines emphasize shared decision-makingespecially when

benefits are small or depend strongly on values and risk tolerance.

Specific example: Prostate cancer screening discussions often highlight that some men may see a

small mortality benefit, while others may experience harms from false positives, biopsies, overdiagnosis, or

treatment complications. The balance shifts with age and risk factors.

5) “You can prevent cancer primarily by manipulating nutrition.”

Nutrition matters. So does body weight, physical activity, alcohol intake, and broader lifestyle patterns. The

“deadly” part comes from overselling nutrition as a precision lever that can reliably prevent cancer in the way

a seatbelt prevents catastrophic injury. Cancer is not one disease, and diet is not one exposure.

Diet patterns associated with healthier outcomes (more plant foods, less processed food, better weight

control) are valuableespecially for cardiometabolic health and for lowering risk of some cancers. But the

stronger evidence tends to support big, boring levers (healthy weight, avoiding tobacco, limiting

alcohol, activity) rather than a single “anti-cancer superfood.”

What “revisited” looks like now: The best nutrition guidance is usually pattern-based and

realistic, not magical:

eat a varied diet, emphasize plant foods, maintain a healthy weight, limit alcohol, and don’t rely on

supplements to do the job of a balanced diet.

Media warning sign: If a headline implies you can “detox” or “starve cancer” with a specific diet,

you’re looking at a story that’s likely mixing mechanistic speculation with human-outcome certainty.

6) “Personalized medicine will reacquaint us with the ‘cure for cancer’any day now.”

Precision medicine has delivered real wins: biomarker-guided therapies, targeted treatments for tumors with

specific drivers, and safer prescribing through pharmacogenomics in some settings. But “personalized” can

also become a buzzword that hides practical constraints: cost, access, tumor heterogeneity, resistance,

limited targets, and the complexity of linking a molecular signature to a life-saving intervention.

What “revisited” looks like now: Precision medicine is less a single cure and more a toolbox:

it can improve the odds for certain patients in certain cancers, and it can refine treatment selection. Yet many

cancers still require combinationssurgery, radiation, systemic therapy, targeted therapy, immunotherapyplus

prevention and early detection where appropriate.

Specific example: Drug labels increasingly include pharmacogenomic biomarkers that guide therapy

selection or safety precautions. That’s a clear, concrete form of personalizationfar from science fiction, but

also far from universal cancer cures.

7) “Cancer chemotherapy is a major public health advance (full stop).”

Chemotherapy is real medicine. It can cure some cancers, shrink tumors, reduce recurrence risk, and extend

life. It’s also toxic, variably effective, and not the sole reason cancer outcomes have improved over time.

The “revisited” point isn’t “chemo is useless.” It’s that public health success is rarely one tool doing all the

work. Declines in cancer mortality reflect multiple forces: reduced smoking, improvements in early detection

for some cancers, better surgery and radiation techniques, more effective systemic therapies (including chemo,

targeted therapy, and immunotherapy), and better supportive care.

What “revisited” looks like now: The smart framing is plural:

cancer control improves through prevention, earlier detection where proven, and a steadily expanding

toolkit of treatmentsincluding but not limited to chemotherapy.

So what do we do with this list in 2026?

The “Seven Deadly” list is not a call to nihilism. It’s a call to better questions. Here are a few that work in

almost any medical story:

- What is the outcome? Does it improve survival, symptoms, function, or quality of life?

- What’s the absolute effect? “Relative risk” without baseline risk is a magic trick.

- Who was studied? Age, sex, baseline risk, comorbidities, and setting matter.

- What’s the evidence tier? Lab data and observational signals are not the same as trials.

- What are the harms? Side effects, false positives, overdiagnosis, cost, opportunity loss.

- Can it be replicated? One study is a starting point, not a finish line.

If you’re a writer or editor, here’s a bonus guideline: whenever possible, make your story disagreeable to hype.

That means including uncertainty, competing explanations, and the difference between “promising” and

“proven.” Your readers will survive the nuance. They might even enjoy it.

Experiences from the real world (about )

The most interesting part of these hypotheses isn’t the academic argumentit’s how they play out in actual

conversations. Consider the adult who schedules an executive “full-body scan package” because it feels like

responsibility. They’re not chasing vanity; they’re chasing control. The idea that “more screening is better”

offers emotional relief: if you can find problems early enough, maybe you can outsmart mortality. Then a

harmless-looking incidental finding turns into a cascademore imaging, a biopsy, a complication, weeks of

anxietyand the final diagnosis is either benign or a slow-growing condition that never needed treatment.

The patient didn’t do something foolish; they followed a culturally rewarded script. The script just left out the

chapter on false positives and overdiagnosis.

Or take the friend who swears by megavitamins. They aren’t anti-science; they’re pro-agency. Swallowing a

supplement is a daily ritual of “I am doing something.” When asked for evidence, they’ll cite a before-and-after

feeling (“I had more energy!”) or a lab value that moved in the “right” direction. What’s hard is explaining that

biology is not a points system: a number can change without changing the outcome you actually care about.

Sometimes, the most compassionate approach is not a lectureit’s a gentle pivot to specifics: “Are you taking

this for a deficiency? Has your doctor checked levels? Could it interact with any meds? What outcome are you

trying to prevent?”

Precision medicine brings its own emotional weather. Patients hear “personalized” and imagine a custom-built

cure. Clinicians, meanwhile, often experience it as a complex decision tree: order biomarker testing, interpret

uncertain variants, balance guidelines with access and insurance, discuss tradeoffs, and plan for resistance.

When a targeted therapy works beautifully, it feels like the future arriving early. When it doesn’t, the gap between

promise and reality can be crushingespecially if the marketing set expectations at “guaranteed.”

Even in research, the first deadly hypothesis shows up as a familiar temptation: “The dataset is huge, so the

result must be true.” Researchers may find a statistically significant association that looks breathtaking in a

graph, only to watch it fade when they adjust for a confounder, test an independent cohort, or attempt a

randomized intervention. The good teams don’t treat that as failure; they treat it as refinement. The best

experience you can have in science is not being right on the first tryit’s learning fast before you scale a

mistake into a movement.

In all these situations, the common thread is human: people want certainty, safety, and a story that makes

sense. Evidence-based medicine doesn’t remove those desiresit just asks us to earn our certainty with better

methods and to tell stories that include the inconvenient parts.

Conclusion

“Seven Deadly Medical Hypotheses revisited” is ultimately an optimism project. It assumes science can improve

when we notice patterns of self-deception earlyespecially the seductive ideas that sound helpful, sell well,

and then crumble under careful testing.

The healthiest stance is neither blind faith nor constant suspicion. It’s disciplined curiosity:

enthusiastic about good evidence, allergic to overclaims, and willing to update when the data change.

And if that sounds less thrilling than a miracle headlinegood. Medicine works better when it’s boring in the

right places.

Important: This article is for education only and is not medical advice. Screening and treatment decisions should be discussed with a qualified clinician who knows your history.