Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- The Setup: How Joan Rivers Became Carson’s MVP Substitute

- Fox Enters the Chat: Why Rivers Took the Risk

- The Betrayal Narrative: Why Carson Took It Personally

- The Fallout: When a Feud Becomes a Business Strategy

- Why This Feud Would Look Different Today

- The Nuanced Take: Two Things Can Be True

- Lessons for Creators (and Anyone Who’s Ever Had a Boss)

- Conclusion: A Feud That Was Really About the Era

- Experiences Related to the Carson–Rivers Feud (Modern Reflections)

If late-night TV were a high school cafeteria, Johnny Carson was the table everyone wanted to sit atand

Joan Rivers was the kid who made the whole room laugh, then got sent to the principal’s office for being “too much.”

Their falling-out wasn’t just celebrity drama. It was a collision of power, loyalty, timing, and a media ecosystem that treated

gatekeepers like weather: unavoidable, occasionally stormy, and never your fault when it ruined your hair.

The twist is that, viewed through today’s lenswhere creators job-hop publicly, networks fight on TikTok, and “brand” is a full-time

sportthis feud would likely play out very differently. Same emotions, different physics. Back then, one phone call (or alleged

phone call) could freeze a career out of an entire franchise. Today? That phone call becomes a podcast episode, a Substack post, a PR

statement, and three reaction videos before lunch.

The Setup: How Joan Rivers Became Carson’s MVP Substitute

A breakthrough that turned into a recurring role

Rivers didn’t become a late-night legend by accident. She fought her way through the era when “female stand-up” was treated like a

novelty categoryright next to “left-handed scissors.” Her early appearances on The Tonight Show helped catapult her into national

visibility, and she became one of the show’s most reliable comedy guestsquick, fearless, and prepared to earn laughs without begging

for them.

Over time, Rivers didn’t just visit Carson’s world; she helped run it when he was gone. By the early 1980s, she had filled in for

Carson dozens of times, and in 1983 she was named the show’s permanent guest hostan unusually prominent platform for a woman in that

late-night era.

Here’s the uncomfortable part: “permanent guest host” is not the throne

The guest-host chair looked like an apprenticeship, but it wasn’t a straightforward ladder. Rivers later described a relationship that

was warm on camera, chilly off itmore professional alliance than best-friends-forever bracelet. That’s not shocking. Carson’s show was

a machine that ran on timing, control, and a very clear hierarchy.

And hierarchies do not love ambiguity. Rivers was close enough to be valuable, visible enough to be threatening, and dependent enough

to be controlled. That combination can workuntil it doesn’t.

Fox Enters the Chat: Why Rivers Took the Risk

The offer wasn’t just moneyit was oxygen

By 1986, Fox was the ambitious upstart trying to build a fourth network identity, and late-night was a flashy way to announce, “We’re

here.” Rivers was offered a show that put her name on the marquee. Not “guest host.” Not “when Johnny’s on vacation.” The top line.

Rivers also believed her future at NBC was uncertain. She pointed to contract signals and internal politics that suggested she might

never inherit anything bigger than the substitute seatespecially as a woman. In her telling, Fox wasn’t just an opportunity; it was an

escape hatch before the door quietly locked behind her.

The successor problem: being essential doesn’t mean being next

Here’s a career truth that has ruined many a confident person’s day: you can be indispensable and still not be the heir. Rivers saw

hints that NBC didn’t view her as “the next Carson,” and that matters, because the substitute role only feels safe until you realize the

job you actually want is not on the list.

In 2026 terms, Rivers was a creator with huge engagement who kept getting offered “more collabs” instead of a channel of her own.

At some point, you stop asking for a bigger slice and go find another bakery.

The Betrayal Narrative: Why Carson Took It Personally

The phone call that became a myth factory

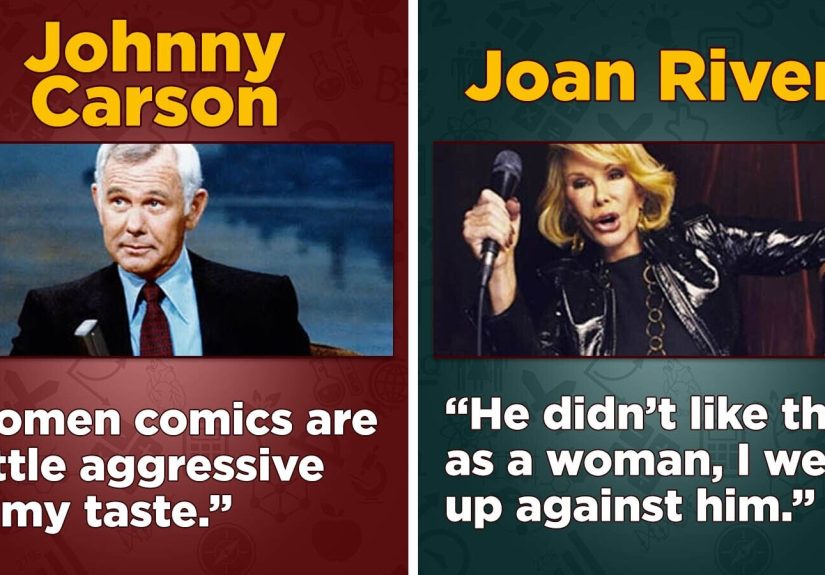

The central dispute still sounds like the setup to a sitcom episode: Rivers said she called Carson first, he hung up, and later denied

she called. Carson, for his part, publicly conveyed that he felt blindsided and betrayed, and that he hadn’t received the courtesy of a

direct conversation before the news broke.

The details matter less than the dynamic: Carson’s camp wanted control over the storyline, and Rivers wanted recognition that she wasn’t

“owned” by the franchise she helped elevate.

Late-night had unwritten rulesand Carson was the rulebook

In the Carson era, the host wasn’t just a performer. He was a kingmaker who controlled access to the biggest platform in comedy. That

meant “leaving” wasn’t interpreted like changing jobs; it was interpreted like defecting to an opposing nation.

And Carson had a particular sensitivity about loyalty. Other regulars tried competing late-night projects over the years, but the Rivers

move landed differentlypartly because Fox’s show was positioned as a direct challenge, and partly because the announcement unfolded in a

way Carson perceived as disrespectful.

The Fallout: When a Feud Becomes a Business Strategy

“Blacklisted” wasn’t a metaphorplatform access was the whole game

Once the relationship broke, Rivers lost access to the most valuable stage in the format. Reports from the period describe an atmosphere

where appearing on Rivers’ Fox show could jeopardize a guest’s future bookings on Carson’s Tonight. Whether enforced via formal

policy or informal fear, the effect was the same: booking became harder, and every guest decision became political.

Fox’s showThe Late Show Starring Joan Riverspremiered in October 1986, a big swing intended to help launch Fox’s network identity.

But it ran into problems quickly: affiliate carriage issues in some markets, noisy behind-the-scenes tensions, and the basic challenge of

competing with a cultural institution.

The show implodedand the personal cost was devastating

By 1987, Rivers was out at Fox. The story is tangledratings pressure, executive conflict, internal clashesbut what’s clear is that the

project collapsed fast enough to turn a bold career bet into a public stumble.

Then came the tragedy that still makes the whole saga feel less like showbiz gossip and more like a cautionary tale: Rivers’ husband,

Edgar Rosenberg, died by suicide in 1987, not long after the firing. It’s hard to overstate how brutal that sequence is: career upheaval,

public humiliation, and private catastrophe stacked back-to-back.

Rivers did what she always did: she worked. She rebuilt her TV presence, reinvented her brand, and kept performing with the kind of

relentless energy that looks funny until you realize it’s also survival.

Why This Feud Would Look Different Today

1) Power is still realbut it’s louder, messier, and more distributed

Carson’s power came from a single, dominant platform. If you lost that platform, you lost visibility. Today, visibility is splintered:

broadcast, cable, streaming, YouTube, podcasts, social clips. A modern Rivers could be “banned” from one flagship show and still talk to

millions before the commercial break would’ve ended in 1986.

2) Mentorship doesn’t read like ownership anymore (at least, not in public)

One of the most modern-sounding tensions in their story is the question of agency: was Rivers a protégé with the right to leave, or a

“discovery” expected to stay loyal? Rivers herself framed it in gendered termssuggesting she was treated differently because she was a

woman who “went up against” the king.

In today’s language, we’d call parts of that dynamic “gatekeeping,” “brand control,” or “workplace politics.” We’d also recognize that

someone can be generous and still be possessiveespecially when their generosity is tied to maintaining a hierarchy.

3) PR and social media would force a faster, more public resolution

Imagine this feud in 2026:

- Rivers’ deal leaks on X before the contracts are printed.

- Carson’s camp issues a “disappointed but wishing her well” statement written by a lawyer.

- Rivers posts a video: “Here’s what really happened,” with receipts.

- Three comedians do bits about it the same nightone goes viral, one gets subtweeted, one gets booked on both shows.

The public would demand a narrative, and both brands would be pressured to show emotional intelligencebecause “silent treatment for 20

years” plays terribly in the era of accountability, even when audiences still love petty drama.

4) Industry norms around women in comedy have changedenough to matter

Rivers broke ground in a business that routinely treated women as exceptions. Today, women host late-night, headline stand-up specials,

and run production companies. It’s still not perfectly equitable, but it’s less plausible for a network to act as though a top female

comic has no viable path besides waiting for a man to retire.

In other words: Rivers’ decision to leave would be read less as “disloyalty” and more as “career strategy,” and the public would likely

debate Carson’s reaction as much as Rivers’ move.

The Nuanced Take: Two Things Can Be True

The cleanest version of this story is “Carson bad, Rivers good” or “Rivers ungrateful, Carson justified.” Real life is rarely that tidy.

Two things can be true:

- Carson helped Rivers in ways that genuinely mattered, and his platform amplified her career.

- Rivers had every right to take a once-in-a-lifetime offerespecially if she believed her long-term future was insecure.

- Carson could reasonably feel blindsided by the rollout and still be wrong to freeze her out indefinitely.

- Rivers could mishandle communication and still deserve professional dignity, not exile.

In today’s workplace vocabulary, we’d call this: a messy offboarding compounded by power imbalance, bruised ego, and a public industry

that treats personal relationships like corporate assets.

Lessons for Creators (and Anyone Who’s Ever Had a Boss)

- Clarify the ladder. If you’re doing “the next-in-line” work, ask whether you’re actually next.

- Don’t confuse access with security. Being close to power can feel like protectionuntil it becomes control.

- Control the rollout. Career moves don’t fail only on strategy; they fail on communication and timing.

- Beware unwritten rules. If a system runs on invisible expectations, breaking them can cost more than you think.

- Plan for the emotional fallout. Even “right” decisions can carry grief, guilt, and backlash.

Conclusion: A Feud That Was Really About the Era

The Carson–Rivers rupture is remembered as a celebrity feud, but it was also a case study in how entertainment power used to work:

centralized, relationship-driven, and punishing to anyone who disrupted the ecosystem.

If it happened today, the fight wouldn’t vanishbut the consequences would be harder to enforce in silence. Modern media rewards

transparency, alternative platforms, and public narrative control. Rivers would have more outs. Carson would have more scrutiny.

And the audiencearmed with context about gender, power, and workplace dynamicswould likely see the story as more than betrayal.

In the end, the saddest part isn’t that two comics stopped talking. It’s that an industry built on laughter couldn’t find a way to

negotiate a breakup without turning it into a life sentence.

Experiences Related to the Carson–Rivers Feud (Modern Reflections)

Even if you weren’t watching late-night in 1986, you’ve probably lived a version of this storyjust with fewer studio lights and fewer

jokes about sequins. The core experience is universal: you’re “the trusted one,” the reliable closer, the person who can fill in when the

star isn’t available. Everyone tells you you’re valued. You start believing the role itself is proof you’re safe.

Then one day you notice something subtle: the praise never turns into promotion. The compliments are generous, but the opportunities

plateau. You’re invited to keep the machine running, not to inherit it. That’s when the Fox offer shows upmaybe not from a TV network,

but from a competitor, a new client, a new platform, a new city. And it feels like oxygen. You tell yourself you’ll handle it carefully,

you’ll do the respectful thing, you’ll communicate. But the timing gets messy, the news leaks, the rumor outruns the conversation, and

suddenly your big step forward is framed as betrayal.

There’s also the experience of being a woman (or any “non-default” person) in a space where you can be exceptional and still be treated

as temporary. You learn to be twice as prepared because mistakes are remembered longer. You become funny, sharp, fastbecause the room

doesn’t forgive slow. Rivers’ whole career radiated that energy: the drive to be undeniable. When you finally get a shot at the top job,

you don’t just see it as ambitionyou see it as survival, as proof that you won’t be erased by someone else’s timetable.

And then there’s the experience of the gatekeeper. People like to imagine gatekeepers as villains, but the lived experience is often

messier. If you’re the person who built the roomwho believes you created the standardyou can start to feel that departures aren’t

neutral. They’re commentary. Someone leaving doesn’t just change staffing; it challenges identity. Carson’s era rewarded that mindset,

because a single platform could enforce loyalty. The modern era doesn’t reward it as much, but you still see it everywhere: “After all

I’ve done for you…” spoken like a receipt no one agreed to sign.

In today’s media landscape, the experience also includes the audience as an active participant. Back then, you might have read a column,

heard a rumor, and moved on. Now, a public falling-out becomes a live debate with teams, threads, memes, and long-form “explainer”

videos. That can be empoweringpeople get heardbut it can also flatten humans into avatars. Someone becomes “the traitor,” someone becomes

“the tyrant,” and nuance dies in the comment section.

What’s most instructive about Carson vs. Rivers is the emotional hangover: the sense that a professional relationship can feel personal

even when it isn’t intimate. Rivers could describe the bond as limited off-camera and still feel crushed by the rejection. Carson could

see himself as a benefactor and still react like he’d been personally wronged. That’s the strange math of careers built in public: the

work is transactional, the feelings are real, and the consequences can outlast the paychecks.

If you’ve ever left a role where you were “the favorite,” you know the aftertaste. You replay the decision, the timing, the message you

sent, the call you madeor didn’t. You wonder whether you could’ve kept the relationship if you’d explained better. And eventually you

learn the hardest lesson: sometimes the relationship was conditional all along, and the condition was that you never become a rival.