Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Table of Contents

- What “Layers” Means (and What It Doesn’t)

- A Quick Detour: Phineas Gage and the “Thinking Brain”

- The Three Systems You Feel During Market Chaos

- Why Uncertainty Feels Worse Than Bad News

- Why Crowds Are Comforting (and Dangerous)

- Why Your Brain Needs Breaks (Yes, Even From Finance)

- Dopamine: The “Maybe I’ll Win” Chemical

- A Layer-by-Layer Investor Playbook

- Systems That Let Your Best Brain Show Up

- Conclusion

- Experiences: What This Looks Like in Real Life (Extra )

If you’ve ever watched your portfolio wobble and suddenly felt the urge to “just do something,” congratulations:

your brain is working exactly as designed. Unfortunately, your brain was designed to keep you alive on a savanna,

not to keep you calm while a line chart does interpretive dance.

The classic “layers of the brain” ideapopularized in many conversations about behavior, stress, and decision-making

is a useful (if simplified) metaphor for understanding why smart people make not-so-smart money moves. The punchline:

you don’t need more intelligence. You need better systems that protect you from your most human moments.

What “Layers” Means (and What It Doesn’t)

When people talk about “layers of the brain,” they’re often referencing a simple three-part story: an older,

automatic survival system; a more emotional system; and a newer, more analytical system. It’s a convenient way to

describe how we can be calm one minute and irrational the nextespecially when uncertainty enters the chat.

A quick reality check: modern neuroscience doesn’t treat the brain like a neat three-tier cake where each tier takes

turns driving the body. The “triune brain” model (the classic three-layer framing) is widely considered an

oversimplification, even if it remains popular because it’s memorable and useful for everyday explanations.

Think of it like a subway map: not geographically perfect, but it helps you get where you’re going.

For investing, the metaphor is powerful because markets constantly poke the exact buttons that trigger fast, emotional

decisions: uncertainty, social proof, reward anticipation, and stress. If you understand the buttons, you can stop

“accidentally” launching yourself into panic-selling or FOMO-buying.

A Quick Detour: Phineas Gage and the “Thinking Brain”

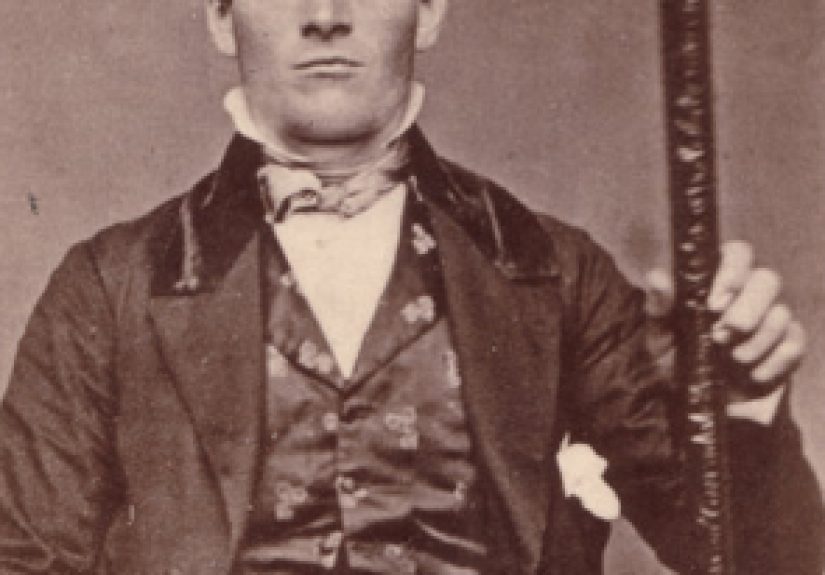

One of the most famous stories in neuroscience is Phineas Gagea railroad worker who survived a catastrophic brain

injury in the 1800s and became a living reminder that the frontal parts of the brain matter for judgment, impulse

control, and social behavior. His story is often used to illustrate that “who we are” isn’t just personality; it’s

also circuitry.

In investor terms: you can be disciplined, rational, and long-term oriented… right up until stress, sleep loss, or

fear yanks the steering wheel. The goal isn’t to pretend you’re above biology. The goal is to build a plan that

works even when your biology is having a dramatic day.

The Three Systems You Feel During Market Chaos

1) The Automatic Survival System: “Fix It Now”

This is the part of you that wants immediate action. It’s great when a car swerves into your lane. It’s not great

when the “danger” is a headline and a red candle on a chart. In markets, this system shows up as:

panic selling, all-in safety trades, or rage-refreshing your portfolio app.

2) The Emotional System: “This Feels Personal”

The amygdalaoften described as a hub for emotional processing, especially fear and anxietyhelps your brain decide

what’s threatening and what needs attention. That’s useful for survival, but it can also make financial volatility

feel like a personal emergency.

In markets, this emotional layer shows up as:

loss aversion (“I can’t stand seeing this down another 3%”), FOMO (“everyone’s making

money but me”), and narrative addiction (“tell me one more thread about why this stock is the future”).

3) The Cognitive System: “Let’s Think This Through”

This is the part that can zoom out, do math, weigh tradeoffs, and say, “Yes, this is uncomfortable, but it’s not new.”

The prefrontal cortex is heavily involved in planning, prioritizing, and decision-making. The problem is that this

system gets quieter under stressexactly when you need it most.

Your best investing outcomes usually happen when the cognitive system sets the rules ahead of time and the

other systems don’t get to rewrite the rules mid-game.

Why Uncertainty Feels Worse Than Bad News

Your brain doesn’t just dislike pain; it really dislikes not knowing when (or how) pain will arrive. Research on

uncertainty shows that unpredictable threat can be especially stressful because the brain keeps scanning for danger,

unable to “close the loop.” In financial markets, uncertainty is basically the house special.

That’s why investors often feel a strange urge to “lock in” an outcomeeven a bad onejust to end the suspense.

It’s also why people can feel relief after selling in a panic: the uncertainty ends immediately, even if the decision

harms long-term returns. The emotional brain values certainty now; the investing brain values compounding later.

The wealth-of-common-sense lesson here is blunt: the discomfort is not a sign you’re doing it wrong. It’s often a sign

you’re doing markets correctly. Markets pay a premium for uncertainty because uncertainty is annoying and humans would

prefer a different hobby, like juggling chainsaws.

Why Crowds Are Comforting (and Dangerous)

Humans are social learners. When everyone around you seems to agree on a story“this sector is unstoppable,”

“that asset is dead forever,” “this time is different”your brain treats the crowd as a safety signal. Following the

group lowers social friction and reduces the emotional cost of being wrong alone.

In markets, crowds can be useful because prices often reflect real information. But crowd psychology becomes

most dangerous at extremeswhen euphoria and fear turn a reasonable trend into a stampede.

The fix isn’t to become a contrarian as a personality trait (nobody likes that guy at parties). The fix is to hold

strong views, weakly held: have principles, but stay humble about predictions. Most of the time, a boring,

diversified plan beats a heroic story.

Why Your Brain Needs Breaks (Yes, Even From Finance)

Chronic stress changes how you think and feel. Stress activates the body’s fight-or-flight response and releases

hormones like adrenaline and cortisol. Over time, that can affect sleep, concentration, and decision qualityexactly

the ingredients you need for patient investing.

There’s also evidence that stress signaling can impair prefrontal cortex functionmeaning the part of your brain that

helps you plan and regulate impulses may get less effective under pressure. In plain English: if you’re stressed,

your “adult in the room” can step out for a smoke break without telling you.

That’s why “just be disciplined” is weak advice. Discipline is easier when your environment supports it: fewer

alerts, fewer forced decisions, and fewer late-night doom-scroll sessions right before you rebalance.

Dopamine: The “Maybe I’ll Win” Chemical

Dopamine is often misunderstood as the “pleasure chemical.” A more useful investing take is: dopamine is deeply tied

to learning, motivation, and predictionespecially when outcomes are uncertain. Dopamine

neurons can respond strongly to unexpected rewards and “prediction errors,” which makes variable rewards (like

gambling or hype-driven trading) extremely sticky for the brain.

That’s why fad investments feel exciting: the brain loves a story with a lottery-ticket-shaped plot twist. And it’s

why the most dangerous phrase in personal finance is: “I’m not investing, I’m just taking a small flyer.”

Congratulationsyou have invented gambling, but with more spreadsheets.

None of this means you can’t take risk. It means you should budget risk. If you want a “fun” sleeve

of your portfolio, fineset a percentage you can afford to lose and keep it contained like a backyard fire pit:

controlled, supervised, and not inside the living room.

A Layer-by-Layer Investor Playbook

When the survival layer is screaming

- Slow the timeline. Make a rule: no portfolio changes within 24 hours of scary news.

- Reduce inputs. Turn off price alerts and stop refreshing. Your brain can’t calm down while you keep poking it.

- Check liquidity. If you truly need cash soon, volatility matters more. If you don’t, volatility is mostly noise.

When the emotional layer is bargaining

- Name the feeling. “I’m feeling fear/FOMO.” Labeling emotions can reduce their grip.

- Separate story from strategy. News is a story. Your plan is a strategy. Don’t let stories rewrite strategies.

- Use diversification as emotional insurance. A well-diversified portfolio can reduce “single-point-of-failure” panic.

When the cognitive layer is online

- Re-read your investment policy statement (IPS). If you don’t have one, that’s your homework.

- Rebalance with rules. Pre-set thresholds remove guesswork.

- Zoom out. Tie actions to long-term goals, not short-term feelings.

Systems That Let Your Best Brain Show Up

Great investing is less about predicting the future and more about managing yourself in the present. That’s why

investor education and advisory research often emphasize staying focused on goals, avoiding impulsive reactions, and

using a processespecially during volatile markets.

1) Automate the good decisions

Automatic contributions, scheduled rebalancing, and target allocations reduce the number of “should I do something?”

moments. Fewer decisions means fewer chances for your stressed-out brain to improvise.

2) Create a “volatility script”

Write down what you will do when markets drop sharply (and what you will not do). Keep it short. Keep it readable.

Put it where you’ll actually see it. The point is to outsource decisions to your calm self.

3) Decide what volatility means for you

Volatility isn’t just a math term; it’s a psychological event. If short-term liquidity needs are real, you may need

a more conservative allocation for that time horizon. If your goal is decades away, you can treat volatility more like

weather: sometimes annoying, rarely personal.

4) Add friction to bad habits

Want to reduce impulsive trades? Make trading harder: remove apps from your phone, require two-factor login, or force

yourself to place trades only from a desktop during business hours. You’re not weak; you’re human. Design accordingly.

5) Use coaching, even if it’s “self-coaching”

Behavioral coaching frameworks emphasize preparing for stressful situations in advance and helping investors stay

aligned with long-term goals during short-term turbulence. Whether that coaching comes from an advisor or a personal

checklist, the advantage is the same: it keeps your emotional layer from running the show when markets get jumpy.

Conclusion

The “layers of the brain” metaphor is a cheat code for investor psychology. Your automatic survival system wants

immediate certainty. Your emotional system wants comfort and belonging. Your cognitive system wants a rational plan.

Markets regularly trigger the first two and then charge you a fee for reacting quickly.

The wealth-of-common-sense approach is to stop fighting your brain and start working with it:

expect uncertainty, build rules ahead of time, automate what you can, and design an environment that makes good

decisions easier than bad ones. You don’t need to be fearless. You just need to be prepared.

Experiences: What This Looks Like in Real Life (Extra )

The theory is nice, but the real proof shows up when your phone buzzes and your stomach drops. Here are a few common,

very human “layers of the brain” experiences investors often describealong with the practical lesson hiding inside

each moment.

Experience 1: The “I Need to Check” Spiral

A market selloff hits. At first you check your account once. Then you check again “just to be informed.” Then again

because the number changed. Soon you’re refreshing like it’s a competitive sport. Your day becomes a loop:

check → feel worse → check to relieve the feeling → feel worse again. This is the survival/emotional combo doing what

it evolved to do: monitor threat signals in real time.

The problem is that markets provide endless “threat signals” without offering a clear moment when the threat is

officially over. So the brain never gets closure. The investing lesson isn’t “be stronger.” It’s “change the inputs.”

Many people find it dramatically easier to stay rational when they turn off alerts, reduce news intake, and set a

single scheduled time to review finances (weekly or monthly). The cognitive layer can’t lead if it’s being heckled

40 times a day by notifications.

Experience 2: The Group Chat That Buys First and Thinks Later

Someone you know posts big gains. Another friend says, “You’re still not in?” A headline declares a “new era.”

You feel behind, even if you were perfectly fine five minutes ago. That’s social proof turning up the volume.

The emotional layer interprets the crowd as safetyand missing out as danger.

The wealth-of-common-sense move here is to separate identity from strategy. If you’re buying because you feel left out,

you’re not investingyou’re trying to relieve a social emotion. A useful trick is to write down the reason for a trade

in one sentence. If the sentence contains the words “everyone,” “hot,” “can’t miss,” or “I’ll hate myself if…,” that’s

your cue to pause. Some investors keep a small, pre-defined “fun money” slice specifically so the emotional layer

gets a sandboxwithout getting the keys to the whole house.

Experience 3: The “Boredom Trade”

Not every mistake happens during panic. Sometimes markets are calm, your plan is working, and you feel… bored.

That boredom can trigger a hunt for excitement: new tickers, new strategies, new “secret signals.” This is where

reward anticipation sneaks in. Uncertain outcomes with a chance of a big win can feel more motivating than a slow,

sensible planeven if the sensible plan is objectively better for your goals.

The lesson: boredom is not a portfolio problem. It’s an entertainment problem. If you’re tempted to trade because

your long-term strategy is “too quiet,” the fix is often to add structure: rebalance quarterly, review annually, and

fill the rest of your time with things that don’t require guessing the future. Your best investing behavior may come

from having a richer life outside your brokerage account. Compounding is powerfulbut it’s also not a reality show,

and that’s kind of the point.

In all three experiences, the common thread is simple: the brain is doing brain things. The goal isn’t to become a

different species. The goal is to create guardrailsrules, automation, and frictionso that your smartest self can

stay in charge when your oldest instincts show up to “help.”