Table of Contents >> Show >> Hide

- Form 8-K in plain English

- Why Form 8-K exists (and why investors care)

- When is Form 8-K due?

- “Filed” vs. “furnished”: the sneaky detail that matters

- What kinds of events trigger a Form 8-K?

- How to read a Form 8-K without getting lost

- Is filing an 8-K “bad news”?

- Does Form 8-K create a separate “duty to disclose everything”?

- What happens if a company files late?

- Concrete examples of what an 8-K might look like in real life

- Conclusion

If Forms 10-K and 10-Q are a company’s “full annual checkup” and “quarterly progress report,” then

Form 8-K is the “Hey, you should probably know this right now” memo.

It’s the SEC’s way of making sure investors don’t have to wait months to hear about major eventslike a big acquisition,

a CEO exit, an earnings announcement, or (yes) a material cybersecurity incident.

Form 8-K in plain English

Form 8-K is a “current report” that publicly reporting companies file with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)

to announce certain significant corporate events that shareholders should know about.

It’s designed to provide timely, standardized disclosure between periodic reports.

Think of it as the market’s official “breaking news” formatless like a novel, more like a headline + receipts.

Sometimes those receipts are exhibits: press releases, credit agreements, merger contracts, resignation letters, or auditor correspondence.

Why Form 8-K exists (and why investors care)

Markets run on information. If important information sits inside a company for too long, trading gets weird:

prices move on rumors, selective disclosures, or half-truths. Form 8-K helps reduce that gap by requiring prompt disclosure

of specific events the SEC has identified as important.

For investors, 8-Ks are useful because they often contain the earliest official details about:

changes in leadership, major financing deals, business combinations, bankruptcy filings, delisting warnings,

earnings releases, auditor changes, or governance updates.

When is Form 8-K due?

In most cases, a company must file (or furnish) a Form 8-K within four business days

after the triggering event occurs. Weekends and SEC holidays don’t count as business days,

so the clock typically starts on the next business day if an event happens when the SEC is closed.

The “four business days” rule, illustrated

- Monday: Company signs a material credit agreement at 3:00 p.m.

- Friday (end of day): Typical latest deadline for the related Form 8-K.

- If it happened on Saturday: the clock usually starts Monday.

Special timing wrinkles: Regulation FD and cybersecurity

Not everything fits neatly into “four business days.” For example:

-

Regulation FD (Fair Disclosure): If a company accidentally reveals material nonpublic information to a select group,

it may need to make public disclosure “promptly” (often tied to a 24-hour/next-trading-day concept in the rule’s definitions).

Companies commonly use an 8-K (Item 7.01 or sometimes 8.01) as part of that public disclosure toolkit. -

Material cybersecurity incidents (Item 1.05): The four-business-day clock typically runs from when the company

determines the incident is materialso the key moment is the materiality determination, not necessarily the first suspicious log-in.

“Filed” vs. “furnished”: the sneaky detail that matters

Here’s a nuance investors often miss: some 8-K information is considered “filed” (with certain liability implications),

while certain items are typically “furnished” instead.

The classic examples are:

Item 2.02 (Results of Operations and Financial Condition) and

Item 7.01 (Regulation FD Disclosure).

This matters because “furnished” information is treated differently under certain legal provisions

than information that is “filed.” Translation: the category can affect how the disclosure is used and referenced later.

(If you’ve ever wondered why earnings press releases often show up as “Exhibit 99.1” attached to an 8-Kthis is part of the reason.)

What kinds of events trigger a Form 8-K?

The SEC organizes Form 8-K into “items”think of them as labeled buckets for different event types.

Not every corporate development requires an 8-K, and not every dramatic headline automatically maps to an item.

But many common “material events” do.

Common 8-K triggers you’ll see all the time

-

Item 1.01 – Entry into a Material Definitive Agreement:

A big contract outside the ordinary course (major loan, significant partnership, merger agreement, etc.). -

Item 1.02 – Termination of a Material Definitive Agreement:

A meaningful breakuplike a major customer contract ending early. -

Item 1.03 – Bankruptcy or Receivership:

The formal “this is not a drill” category. -

Item 1.05 – Material Cybersecurity Incidents:

Required disclosure about the incident’s material aspects and impacts (as applicable under the rules). -

Item 2.01 – Completion of Acquisition or Disposition of Assets:

The “we bought/sold something big” update after the deal closes. -

Item 2.02 – Results of Operations and Financial Condition:

Often used for earnings releases and related presentations (frequently “furnished”). -

Item 2.03 – Creation of a Direct Financial Obligation:

New debt, guarantees, or major off-balance-sheet arrangementsbasically, “we took on a big financial commitment.” -

Item 3.01 – Notice of Delisting or Listing Rule Noncompliance:

The exchange equivalent of a warning light turning on. -

Item 3.02 – Unregistered Sales of Equity Securities:

Issuing shares without registration in a private placement (and needing to tell the market). -

Item 4.01 / 4.02 – Changes in Accountants or Reliance on Financial Statements:

Auditor changes or “we can’t rely on previously issued financials” are major red flags. -

Item 5.02 – Departure/Election of Directors or Certain Officers:

CEO/CFO changes, resignations, new appointments, and sometimes compensation-related updates. -

Item 5.03 – Amendments to Articles/Bylaws; Change in Fiscal Year:

Governance housekeepingsometimes routine, sometimes a big deal. -

Item 7.01 – Regulation FD Disclosure:

Public disclosure of material information shared (or accidentally shared) selectively (frequently “furnished”). -

Item 8.01 – Other Events:

The “none of the above, but investors should still know” optionoften used carefully. -

Item 9.01 – Financial Statements and Exhibits:

Where the attachments live (press releases, agreements, presentations, etc.).

How to read a Form 8-K without getting lost

A good 8-K reading routine is simple: don’t start with the fine printstart with the map.

Here’s a quick approach that works whether you’re a casual investor or a full-time filings nerd.

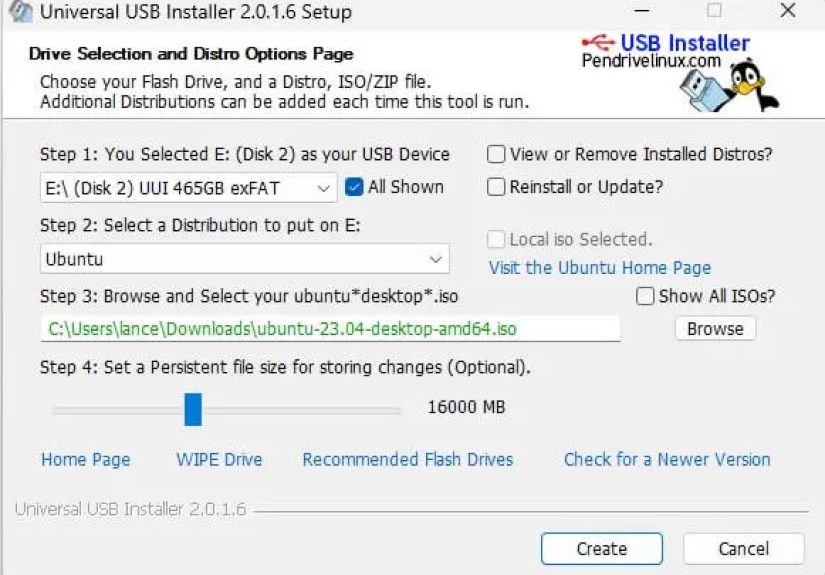

Step 1: Identify the event and the clock

- Look for the “Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported)”.

- Scan the item numbers (1.01, 2.02, 5.02, etc.). They tell you the category instantly.

- Check whether this is an amendment (8-K/A), which often means details became available later.

Step 2: Read the summary paragraph like a detective

Companies often describe what happened and then point to an exhibit.

The exhibit is frequently where the “real” detail livesespecially for earnings releases (Item 2.02),

investor decks, and definitive agreements.

Step 3: Look for what’s missing (politely)

Form 8-K is not a gossip blog. It won’t always give you every number you want.

For example, a company might disclose a deal but omit certain confidential terms, or describe a cyber incident

without giving attackers a helpful how-to guide. Missing detail doesn’t automatically mean something shady

but it’s a cue to watch for follow-up disclosures in a later 8-K/A, 10-Q, or 10-K.

Is filing an 8-K “bad news”?

Not necessarily. Some 8-Ks are genuinely serious (bankruptcy, non-reliance on financials, delisting notices).

Others are routine (annual meeting date updates, certain governance changes).

And some are neutral-to-positive (a new CEO with a strong track record, closing an acquisition, announcing strong results).

The smarter question is: Why did this event require disclosure, and what does it change about the business?

The answer is usually in (a) the item category, (b) the exhibit, and (c) what management says about impact.

Does Form 8-K create a separate “duty to disclose everything”?

NoForm 8-K is a rule-based disclosure system for specific events, plus limited voluntary disclosure space (Item 8.01).

In practice, companies and counsel often treat 8-K drafting like walking a tightrope:

disclose what’s required, be accurate and complete, avoid misleading omissions, and don’t accidentally create new problems.

What happens if a company files late?

Late filings can create headachesregulatory risk, investor relations fallout, and complications for capital markets activity.

The SEC has also historically built in a limited safe harbor for certain items related to failing to timely file an 8-K,

and there are important nuances around eligibility to use certain short-form registration statements (like Form S-3)

depending on the circumstances and items involved.

The practical takeaway is simple: companies try very hard not to miss 8-K deadlines,

and when they do, there’s usually a story behind it (complex facts, materiality calls, coordination across teams,

or waiting for information to become available).

Concrete examples of what an 8-K might look like in real life

Example 1: The “new credit facility” 8-K (Item 1.01 + 2.03)

A company replaces its revolving credit line with a bigger facility at a different interest rate and new covenants.

Expect an 8-K describing the agreement, key terms, and attaching the credit agreement (or a summary plus exhibit references).

Investors often watch for covenant tightness, borrowing capacity, and whether the deal signals financial stressor simply refinancing.

Example 2: The “earnings release” 8-K (Item 2.02, often furnished)

Many companies “furnish” an earnings press release under Item 2.02 and attach it as an exhibit.

The 8-K itself might be short, but the exhibit can contain KPIs, forward guidance, and non-GAAP measures.

This is where investors learn the “why” behind the quarter, not just the “what.”

Example 3: The “CEO transition” 8-K (Item 5.02)

When a CEO resigns, is terminated, or a new CEO is appointed, companies typically disclose the change and often describe

any related employment agreements, severance arrangements, or compensation packages (sometimes via exhibits).

Investors read these closely because leadership transitions can materially change strategy, risk tolerance, and execution.

Conclusion

Form 8-K is the SEC’s current-report system for major corporate eventsbuilt to keep investors informed between 10-Qs and 10-Ks.

If you want to understand a company’s “what just happened,” 8-Ks are often the first official stop.

Read the item number, then read the exhibits, and you’ll usually get the cleanest picture available in real time.

Bonus: Experiences related to “What Is Form 8-K?” (a 500-word, real-world-style add-on)

The most memorable thing about Form 8-K isn’t the form itselfit’s the four-business-day adrenaline.

In many companies, the moment someone says, “This might be an 8-K,” the atmosphere changes. Calendars clear.

Legal and finance suddenly speak in short sentences. Someone inevitably asks, “What time did it happen, exactly?”

because the deadline math can depend on the moment the triggering event occurred (or, in some situations, the moment

management makes a key determination).

One common experience is the “agreement signed, now what?” scramble. A business team finalizes a major customer deal

or signs a credit facility, and the first draft you see is… not exactly investor-friendly. It might be 85 pages of dense terms,

defined words that refer to other defined words, and a covenant package that reads like it was designed by a committee of

lawyers (because it was). The 8-K team then has to translate: What’s the headline? What’s material? What terms must be

summarized? And what can be omitted without leaving investors with a misleading half-story?

Another familiar scenario is earnings season, where an 8-K can feel like a delivery vehicle for a press release that’s already

been polished for weeks. But even then, the “furnished vs. filed” distinction pops up in the background like a stagehand moving

props: finance wants flexibility, legal wants precision, investor relations wants clarity, and everyone wants to avoid making

the numbers sound better (or worse) than they really are. The exhibit attachments matter because they become the official,

timestamped version of what the company told the market.

Then there’s the investor side experience: the EDGAR refresh ritual. Professional investors, analysts, and journalists often scan

8-Ks because they’re fast signals. An Item 4.02 about non-reliance on financial statements? That’s not “interesting,” that’s

“drop everything.” A delisting notice item? That’s a risk-management conversation. A CFO departure? That could be routineor

it could be the start of a broader storyline. People learn to read the item number first because it’s the quickest clue to whether

the disclosure is a weather update or a hurricane warning.

Finally, many teams have lived through the “we need an amendment” moment. Sometimes information isn’t available by the initial

deadlinedetails are still being confirmed, numbers are still being finalized, or the scope of an incident is still unfolding.

The first 8-K goes out with what’s known, and a follow-up 8-K/A fills in the blanks when the company can do so without guessing.

That cycledisclose what you know, update as facts hardenis one of the most practical lessons Form 8-K teaches: markets can

handle uncertainty better than silence, as long as the disclosure is honest, timely, and consistent.